Fracking

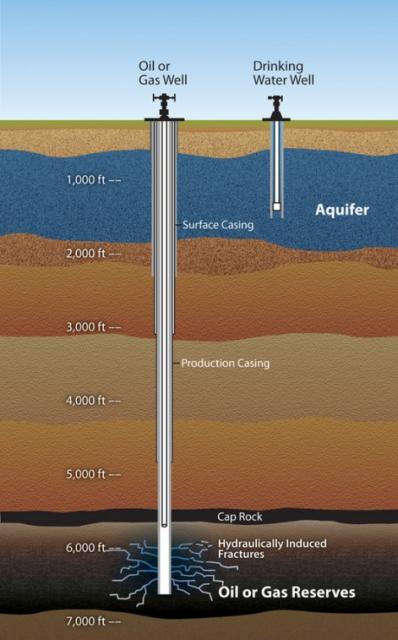

Hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking, injects high pressure volumes of water, sand and chemicals into existing wells to unlock natural gas and oil. The technique essentially fractures the rock to get to the otherwise unreachable deposits.

The Monterey Shale, a geologic formation running the length of the San Joaquin Valley, has been a particular focus and is believed to be home to large amounts of untapped crude. There also has been exploratory fracking elsewhere in California, including well sites along the edges of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta—though the more permeable soil there makes it less attractive to operators. Informal evidence also suggests that the majority of California’s wells may already be fracked, particularly in Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Kern, Ventura and Monterey counties.

While hydraulic fracturing has taken place in California for about 50 years, the use of fracking has grown in the past decade and along the way the technique has generated controversy due to water quality and earthquake concerns.

California’s fracking industry also differs from other states. Elsewhere, fracking done for natural gas production involves large operations. The fracking in California is primarily for crude oil rather than natural gas and occurs on a smaller scale.

Fracking Issues

To reach the oil and gas deposits, operators use a mix of roughly 95 percent water, sand and other material combined with a solution of chemicals (oil companies tend to keep the chemical ingredients secret). Drillers then have to break through thick rock. This process creates fissures where the fracking fluid can spread to other wells or migrate elsewhere. For instance, water that returns to the surface after injection, known as flowback water, retains some of the chemical composition from the fracking fluid.

Fracking also is water intensive, and can use up to 3 to 5 million gallons of water in a single operation according to the Sierra Club.

With this mind, environmental advocacy groups and others have asked for a halt to fracking until the risks to groundwater, and by extension drinking water, are better understood and the chemical nature of the fluid is more transparent. There also is concern about the possible link between the injection of fracking wastewater into the ground and seismic activity. Meanwhile, fracking supporters, particularly the oil and gas industry, have advocated for allowing the practice while ensuring aquifers and adjacent groundwater wells are protected.

California is the fourth largest producer of crude oil in the United States and has a long history of oil exploration.

Fracking Going Forward

At the federal level, the Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Energy and Department of Interior are assessing the potential impacts of fracking on drinking water, wastewater treatment, and the potential for spills. The Bureau of Land Management also has weighed in on the issue.

At the state level, California’s Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources, oversees oil drilling operations.

As of 2014, a California law requires oil companies to test groundwater, notify neighbors, and list the chemicals used on the Internet prior to fracking operations. The law also regulates the injection of acid solutions into the wells to release hydrocarbons.

The Obama administration in 2015 issued rules requiring disclosure of chemicals and covered storage of waste for fracking on federal property. More than 90,000 oil and gas wells are fracked on federally managed lands.

The regulations for federal lands would have required companies to publicly disclose the chemicals used for fracking, in which high-pressure water and chemicals are pumped deep underground to break shale rock and release the oil and gas trapped inside.

Companies also would have been required to use covered storage tanks for fracking waste rather than open pits, a requirement that was made in order to protect groundwater.

In December 2017, the Trump administration rescinded the 2015 federal rules on fracking.