A Key Player On Colorado River Issues Seeks To Balance Competing Water Demands In The River’s Upper Basin

WESTERN WATER Q&A: Colorado’s water chief Becky Mitchell, now the state’s point person on the Upper Colorado River Commission, brings decades of water know-how to state, interstate assignments

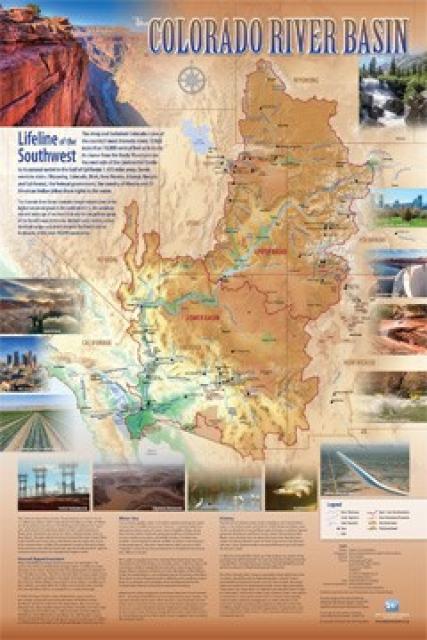

Colorado is home to the headwaters

of the Colorado River and the water policy decisions made in the

Centennial State reverberate throughout the river’s sprawling

basin that stretches south to Mexico. The stakes are huge in a

basin that serves 40 million people, and responding to the water

needs of the economy, productive agriculture, a robust

recreational industry and environmental protection takes

expertise, leadership and a steady hand.

Colorado is home to the headwaters

of the Colorado River and the water policy decisions made in the

Centennial State reverberate throughout the river’s sprawling

basin that stretches south to Mexico. The stakes are huge in a

basin that serves 40 million people, and responding to the water

needs of the economy, productive agriculture, a robust

recreational industry and environmental protection takes

expertise, leadership and a steady hand.

Colorado has that in Becky Mitchell, director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board since 2017 and the second woman to lead the state’s primary water management agency in its 83-year history.

A key player in one of the West’s flash points of balancing competing water demands, Mitchell was a significant contributor to the Colorado Water Plan, the inaugural 2015 document that aims to establish measurable objectives, goals and actions by which the state will address its projected future water needs.

The Water Plan is predicated on the sobering reality that the state may face a significant water supply shortfall within the next few decades. Solving that means finding ways to close the gap between projected supply and demand by 2030 while setting out objectives for water conservation, storage (including groundwater recharge), agricultural use and stream health.

“Colorado is the headwaters state and a lot of the decisions we make here have influence and impact on the other states.”

~ Becky Mitchell, director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board

In 2019, Mitchell’s water portfolio grew when she was appointed by Gov. Jared Polis to serve as Colorado’s representative to the five-member Upper Colorado River Commission, the interstate partnership that ensures the Upper Basin’s delivery obligations to the Lower Basin while safeguarding the water rights and allocations for the Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming.

In a recent interview with Western Water, Mitchell talked about the work behind the Colorado Water Plan, the challenges of establishing a demand management program to meet conservation goals and the prospects for future Colorado River operations.

WW: How did you become interested in water issues?

MITCHELL: I was a consulting engineer before coming to work at the state, so my water background is from the engineering perspective. I have spent about 20 years working in water, primarily in Colorado, but some international work. Colorado is the headwaters state and a lot of the decisions we make here have influence and impact on the other states.

WW: You’ve been with the Upper Colorado River Commission since last July. What’s been you your impression?

MITCHELL: Being the

director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, I had existing

relationships with not only the Upper Basin states but the Lower

Basin states. I have been incredibly impressed how well we work

together at the Upper Colorado River Commission. There have been

other changes — Todd Adams took over for Utah and John D’Antonio

was appointed right before me from New Mexico, so we all had some

existing pre-relationship. And Pat Tyrrell, of course, from

Wyoming, whom I have known for almost all my water career.

MITCHELL: Being the

director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, I had existing

relationships with not only the Upper Basin states but the Lower

Basin states. I have been incredibly impressed how well we work

together at the Upper Colorado River Commission. There have been

other changes — Todd Adams took over for Utah and John D’Antonio

was appointed right before me from New Mexico, so we all had some

existing pre-relationship. And Pat Tyrrell, of course, from

Wyoming, whom I have known for almost all my water career.

As Colorado’s representative to the commission, my goal is to ensure that the state’s interests are represented with respect to the commission and Upper Division states, but also throughout the entire Colorado River Basin. My fellow commissioners and I prioritize maintaining the interstate cooperation and relationships among the seven states that has existed for nearly a century. In the Upper Basin, in particular, we have always felt that our strength is in our ability to reach consensus and identify collaborative approaches.

WW: Can you talk about the 2015 Colorado Water Plan? It seems like it was a monumental achievement for the state and the Upper Basin as a whole.

MITCHELL: Not only was it a big lift but it was an important moment for Colorado. We had done a fair amount of technical work … but not really pushing as far into the policy realm that we needed to go and start looking at how we move that roadmap of goals and objectives to where it needs to be. It addresses everything: our need for a healthy economy, which is obviously extremely highlighted now [amid the coronavirus pandemic], productive agriculture, a robust recreational industry which is vital to our economy and conserving the environment through natural streams and lakes. The Water Plan really pulled everything together in one document and pulled the community together at the same time.

Age: 46

Education: Bachelor’s and master’s degrees, Colorado School of Mines.

Previous jobs: Consulting engineer, public and private sector. Water policy and issues coordinator, Colorado Department of Natural Resources. Section chief, Colorado Water Conservation Board.

Fun Fact: Mitchell has been to Ethiopia nine times, working on different water projects, primarily in the northern region where she also spends time working with a children’s home.

WW: How does the Colorado Water Plan address existing and future needs?

MITCHELL: One of the objectives is to attain 400,000 acre-feet of storage but also a water conservation goal of 400,000 acre-feet by 2050. This really is an example of Colorado’s efforts to consider our obligations in working with the other states. While the Water Plan is a state of Colorado effort, it helps position us within the broader water management context. The Water Plan relies on strong local level planning that focuses on issues unique to each basin. The basin roundtables are currently in the process of updating their implementation plans to identify each basin’s future water needs. The water development and conservation projects at the local level will ultimately allow Colorado to meet its larger Water Plan goals.

WW: How do you see a demand management program happening in the Upper Basin?

MITCHELL: There are

many challenges. We really are a ground-up state and we look to

our water users across the state and build up from that. When we

are looking at a future demand scenario, we are talking to all

our water users, whether that’s municipal or agriculture, about

how to use water more efficiently. I really do feel like Colorado

has taken the lead on investigating the feasibility of a

potential demand management program and the Colorado Water Plan

is driving how we are looking at such a program in Colorado and

the Upper Basin. In Colorado’s plan, we talked about a temporary,

voluntary and compensated reduction in consumptive use of water

from the Colorado River. This investigation includes bringing

together various stakeholders … and really focusing on attempting

to analyze the key threshold issues. Nothing is a done deal. We

have to decide as a board, how do we move forward and if it’s

worth it. We have to determine if demand management is feasible

and we still have to work with the [other] Upper Division states.

MITCHELL: There are

many challenges. We really are a ground-up state and we look to

our water users across the state and build up from that. When we

are looking at a future demand scenario, we are talking to all

our water users, whether that’s municipal or agriculture, about

how to use water more efficiently. I really do feel like Colorado

has taken the lead on investigating the feasibility of a

potential demand management program and the Colorado Water Plan

is driving how we are looking at such a program in Colorado and

the Upper Basin. In Colorado’s plan, we talked about a temporary,

voluntary and compensated reduction in consumptive use of water

from the Colorado River. This investigation includes bringing

together various stakeholders … and really focusing on attempting

to analyze the key threshold issues. Nothing is a done deal. We

have to decide as a board, how do we move forward and if it’s

worth it. We have to determine if demand management is feasible

and we still have to work with the [other] Upper Division states.

WW: Colorado recently launched a tool called Future Avoided Cost Explorer (also referred to as FACE:Hazards) to quantify its existing and future risk to climate hazards such as drought, flood or wildfire and the potential savings from targeted mitigation and adaptation actions. What is its significance and how does it help achieve the goals of the Water Plan?

MITCHELL: The Future Avoided Cost Explorer empowers communities to develop neighborhoods, invest resources and recover from disasters with data and climate-informed decisions that reduce our risks to natural hazard impacts. There are many ways this resource can help further the goals of the Water Plan, but above all, this interactive dashboard helps decision-makers to understand economic risks. FACE:Hazards builds on the climate change scenarios developed in the 2015 Colorado Water Plan and several modeling assumptions in the 2019 Technical Update.

Colorado is home to the headwaters of its namesake river,

seen here at Gore Canyon, about 50 air miles west of Boulder,

Colo. The river’s water supports many uses, including irrigation

and recreation across seven Western states. Video by Mitch

Tobin/WaterDesk.org

WW: How have the 2007 Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations performed and what possible changes do you think we could see in 2026 when the Guidelines are renegotiated?

MITCHELL: I would be stepping out in front of not only my state but all our partners if I said this is exactly what we need to see in the renegotiations. We are still in the early stages of the discussion, so nothing has been determined exactly on the next set of guidelines. Primarily, we are trying to stay focused on the [Bureau of Reclamation] technical review of the effectiveness of the 2007 Guidelines. I think a lot will come out of that. We are trying to keep our eyes on the prize this year and once [Reclamation’s review] is completed, we can start the discussion of what potential Colorado River operations could look like in the future.

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.