Groundwater

If California were flat, its groundwater would be enough to flood the entire state 8 feet deep. The enormous cache of underground water helped the state become the nation’s top agricultural producer. Groundwater also provides a critical hedge against drought to sustain California’s overall water supply.

In years of average precipitation, about 40 percent of the state’s water supply comes from underground. During a drought, the amount can approach 60 percent.

Sources

Groundwater comes mostly from snowmelt and rain percolating through soil and rock and from overland rivers, streams and other waterways. The infiltration is gradual, driven by gravity. Groundwater will flow toward rivers, lakes or the ocean to begin the cycle anew. Groundwater can be pumped or flow naturally to the surface through seepage or springs.

Groundwater can be thousands of years old, although typically it is pumped within years or decades after it originally moved underground through porous material called aquifers.

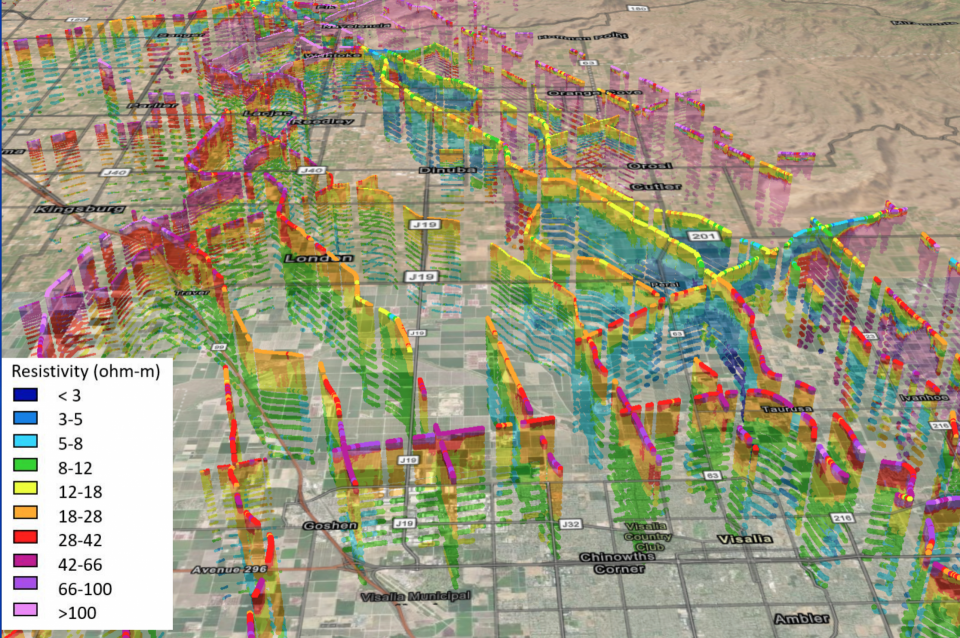

Aquifers can be several feet, or several thousand feet thick. California’s alluvial aquifers are composed of gravel, sand, silt and clay eroded from surrounding rocks and deposited by running water and wind.

California’s Underground Supply

Exactly how much water can be stored within California’s 515 alluvial groundwater basins and subbasins is unclear. The state Department of Water Resources (DWR) estimates their total storage capacity at more than 850 million acre-feet, more than 10 times that of all the state’s surface reservoirs. One acre-foot is enough to supply two to three households annually in California.

About 83 percent of Californians rely on groundwater for some portion of their water supply. The amount of groundwater used in a community’s water supply varies considerably, depending on the availability of surface water supplies and the cost to pump, treat and distribute groundwater.

California’s largest and most heavily used groundwater basins are in the Central Valley, where aquifers are generally permeable. DWR estimates as many as 2 million wells tap the underground supply.

Groundwater is also heavily used in the Salinas and Santa Clara valleys, the coastal plains of Los Angeles and Orange counties, and the interior basins of Riverside, San Bernardino and Inyo counties.

Interconnection with Surface Water

The state’s surface water and groundwater are intimately connected. Rivers and creeks are fed from groundwater, which, in turn, is recharged by surface water. Surface water diversions can deplete groundwater just as groundwater pumping can reduce the flows of nearby waterways.

Polluted surface water degrades

groundwater and groundwater contaminants affect surface water

quality. The use, transfer, depletion or contamination of one can

directly affect the other.

Polluted surface water degrades

groundwater and groundwater contaminants affect surface water

quality. The use, transfer, depletion or contamination of one can

directly affect the other.

Flood and furrow irrigation and unlined irrigation canals are important sources of groundwater recharge. Many factors affect the rate of rainwater absorption. The amount of water that reaches the water table is called natural groundwater recharge.

How much recharge occurs depends upon river conditions, the rate and duration of rainfall and irrigation, soil moisture, the water table depth, and the soil type. It generally takes several years of average precipitation to recharge aquifers in California to pre-drought levels.

The time it takes for infiltrating water to reach an aquifer as deep as 400 feet may take hours, days, or even years. In some flood-irrigated areas, groundwater levels in nearby domestic wells rise within a few hours to days of flooding.

Challenges

Some communities in Orange and Sonoma counties and elsewhere have figured out ways to better manage their groundwater. Other communities that have pumped too much groundwater wrestle with the consequences, including:

- Land subsidence

- Drying of wells

- Reduced stream flows

- Loss of wetlands and associated aquatic species

- Seawater intrusion into coastal aquifers

Some groundwater is polluted with natural elements leached from the earth, including chromium, radon, boron and arsenic. Other contamination comes from industrial and agricultural wastes in the form of synthetic pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, cleaning solvents and fuel ingredients. [See also Nitrate Contamination and Groundwater Treatment.]

Land subsidence from groundwater pumping continues in many areas of California, some places at a rate of more than 1 foot a year. In the San Joaquin Valley, subsidence has damaged and slowed the conveyance of surface water through the California Aqueduct, Delta Mendota Canal, Friant-Kern Canal and San Luis Canal, as well as private canals, bridges, pipelines and storm sewers.

Management

Until recently, California did not regulate groundwater use beyond the general dictum of putting it to a “beneficial” use. [See Groundwater Law.] A new era of groundwater management began in 2014 when Gov. Jerry Brown signed the landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

The law empowers local officials to

halt the trend of “critically overdrafted” or depleted basins.

Under SGMA, high- and medium-priority groundwater basins were

required to establish local Groundwater Sustainability Agencies

to manage their basins or submit an alternative plan that meets

the goals of the law.

The law empowers local officials to

halt the trend of “critically overdrafted” or depleted basins.

Under SGMA, high- and medium-priority groundwater basins were

required to establish local Groundwater Sustainability Agencies

to manage their basins or submit an alternative plan that meets

the goals of the law.

Those agencies must create and adopt “sustainability” plans acceptable to state water regulators that halt overdraft in groundwater basins and bring pumping and recharge into balance. For critically overdrafted basins, balance must be achieved by 2040. High- and medium-priority basins must do so by 2042. Local sustainability plans began to be implemented in 2020.

Improving recharge is key to most plans and involves multiple steps –finding underground conditions that can best capture and store groundwater, building infrastructure to deliver the water, and having upstream storage to hold peak flows for replenishing aquifers.