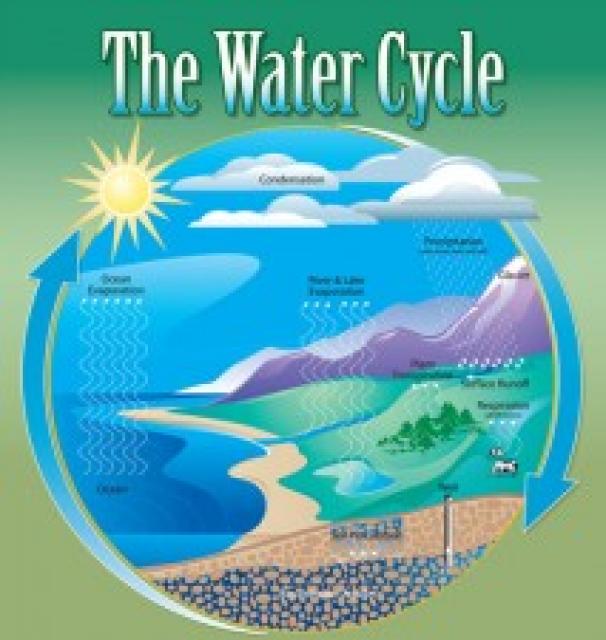

Hydrologic Cycle

Both surface water and groundwater are connected through the hydrologic cycle, essentially the life span of a drop of water.

A drop of water can be birthed, say, by precipitation in the Sierra Nevada range—home to much of California’s runoff.

Freed from the snowpack by a warm ray of sun, the drop seeps into a crack of Sierra granite, bubbles out of the fracture into a spring then into a cascading stream, seeps back into the cobbles, reemerges into the sunlight as the river spills into the valley, soaks into the sands underlying a slow-moving pool, and flows through buried gravels into a low-lying marsh, and then flows to the ocean and is evaporated, starting the cycle again.

The water evaporates to become clouds, the clouds condense to become rain and snow, and so on. But each of these components, be it as a solid, gas or liquid, inevitably remains part of the water equation and are recycled from form to form and from use to use.

Watch a video on how the Hydrologic Cycle works

Precipitation then seeps into the earth to become groundwater, later resurfacing in a spring, river or spring-fed lake. Hydrologists estimate that as much as 30 percent of the water found in lakes or streams comes from groundwater. The use, transfer or contamination of one can directly affect the other.