Groundwater is the ‘neglected child’ of the water world, these authors say

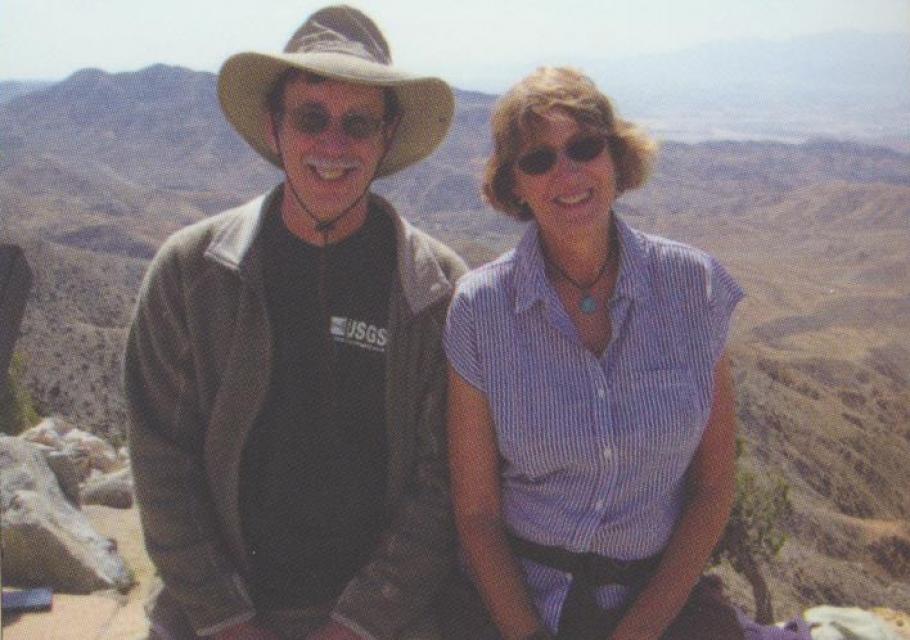

Talking groundwater with authors William and Rosemarie Alley

The phrase “groundwater management” has become commonplace in news headlines throughout California as implementation of the state’s landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) moves into high gear. Following the state’s severe drought, the value of groundwater has become even more apparent so it seemed like a good time to chat about the groundwater story with the husband and wife team of William (Bill) Alley, the director of science and technology for the National Ground Water Association and former chief of the Office of Groundwater for the U.S. Geological Survey, and science writer Rosemarie Alley.

Together, they wrote High and Dry: Meeting the Challenges of the World’s Growing Dependence on Groundwater, which was published earlier this year. The book contains anecdotes from around the United States and the world with chapter titles, such as “Beyond rain,” “Not all aquifers are created equal” and “That sinking feeling.”

What’s the take-home message of High and Dry?

Rosemarie: Groundwater is the neglected child of the water world. Most attention is on surface water, and it’s only every once in a while you will hear about groundwater. But certainly, groundwater overdraft and water quality problems are not just issues here in the United States; they are global issues and are continuing to become more serious.

Why is groundwater of particular interest?

Bill: First, a lot of our drinking water comes from groundwater. Worldwide, almost half of all drinking water comes from groundwater. Second, it’s intimately tied with food security and food production. Groundwater contributes to more than 40 percent of global food production. It’s a critical factor in both health and economic growth by industry. Then, of course, groundwater is intimately tied with surface water and ecosystems. Whether those ecosystems are in wetlands, springs or streams, groundwater is a major factor there.

What’s the importance of knowing how much groundwater there is in California?

Bill: This question comes up a lot. But it’s not one of the most

important things to know about groundwater. With most aquifers,

long before you start running out of water, you have other

factors that come into play, including streamflow depletion or

land subsidence. These types of problems generally become the

controlling issues related to groundwater development. That is

why in California, SGMA has these various critical features. For

example, the Central Valley has lots of groundwater left. It’s

not a matter of running out of water in the Central Valley, but

you can’t pump it all because you have these serious problems

with land subsidence and water quality and surface water

depletion.

What lessons can we learn about groundwater from other parts of the world?

Rosemarie: We are talking about best management practices here. There’s a similar characteristic globally that is making progress in terms of good management of this resource. They all tend to have the focus on local solutions with the very important additional factor of external pressure.

But local doesn’t mean small or simple. With groundwater, there are many stakeholders. Look at what’s going on in California with SGMA and the groundwater management districts – it is hugely complicated with all of the players at the table trying to put together a good operational policy and programs to manage the resource.

Also, it takes time. Places that recognize this and work from the local level instead of thinking they can just hand down the policy and rules from on high, tend to be much more effective in the long run. Groundwater problems are slow to develop; they are slow to solve. It takes time to solve them.

Also, solving groundwater problems requires the scientists and groundwater professionals to work with the public and not just hand down the studies or the results of studies. It’s a new model.

How do we maximize the efficiency of how we use groundwater?

Bill: You might refer to groundwater as an “insurance policy” for drought. But unfortunately, we haven’t learned how to manage it that way. When it gets wet, everyone forgets about the issues and pumps until their hearts’ content. So what we end up doing is simply intensifying over exploitation of groundwater resources during drought. I think one of the keys to better efficiency is to try to find ways and incentives to encourage [using] surface water during wet periods and prepare for increased groundwater use during drought. Of course, the key part of that is recharge, which can be potentially a critical element of drought planning.

What’s it like to write as a husband and wife team?

Rosemarie: I recommend it to everyone; it’s great! You have so many interesting conversations. Rarely did Bill and I disagree. Bill knows a lot more than I do about the data aspect of groundwater. My job is to make it interesting and make sure it’s understandable for a general reader. Our goal always is to try to reach the general public. And we work really hard to tell good stories to make it interesting and very understandable.

To buy the book, visit Yale University Press or Amazon.com