Translating Snowpack into Usable Data is Tricky Business

The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) will conduct its final snow survey of the season within the next two weeks, shining a clearer light on the summer’s water picture and lingering drought conditions.

The data collection and subsequent

forecasting will provide vital information for water supply

operations and allocations to districts and contractors around

the state. More snow means basically more water for downstream

users – whether city residents or rural farmers.

The data collection and subsequent

forecasting will provide vital information for water supply

operations and allocations to districts and contractors around

the state. More snow means basically more water for downstream

users – whether city residents or rural farmers.

Sticking a measuring pole into the snow in the Sierra and crunching the numbers to create a forecast has been done since 1928. Current forecasting efforts and the state’s data network are the backbone of crafting a drought response and an early-warning system for flood emergency response.

Yet we need to keep snowpack measurements in perspective. Forecasting is tricky business and even if forecasts are off by slight percentages, the consequences are real, said David Rizzardo, the state’s chief of the snow surveys and water supply forecasting, during an April 26 briefing coordinated by DWR and the Water Education Foundation at CSU Fresno. “We are only as good as our data. The data ties it all together.”

Uncertainty and margins for error are part of the equation. Think of it this way: if weather forecasters have difficulties predicting weather a week in advance, imagine the task of DWR professionals in spring trying to forecast how much water will be available during summer months even while much of the snow is falling.

“There is uncertainty,” Rizzardo said. “There is

uncertainty in February and March forecasts because weather still

is occurring. April gets a bit more certain. In May, we can be on

track, yet we still are at Mother Nature’s mercy.”

“There is uncertainty,” Rizzardo said. “There is

uncertainty in February and March forecasts because weather still

is occurring. April gets a bit more certain. In May, we can be on

track, yet we still are at Mother Nature’s mercy.”

Contributing to the challenge is the geography of the Sierra Nevada. Although one mountain range, it varies quite a bit. For example, the northern Sierra around the Feather River peaks at around 9,000 feet, whereas the average elevation of the southern Sierra is around 8,500 to 9,000 feet. That means the northern Sierra is non-snow driven – winter precipitations falls more often as rain than snow – whereas higher elevations receive more snow. As a result, snowpack and runoff times vary greatly.

In addition, there’s more to surveys than measuring snow depth. The density of snow and water content are important factors. The rule of thumb is each 10 inches of snow melted will produce one inch of water. That inch of water over an acre produces 2,715 gallons. Of course, actual amounts vary considerably depending on whether the snow is heavy and wet or powdery and dry.

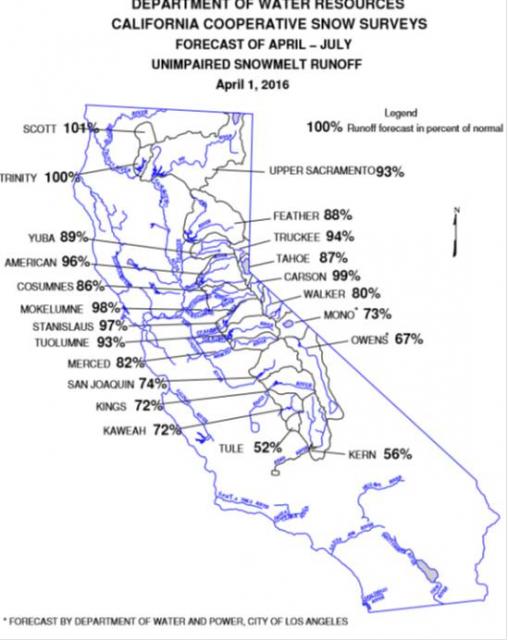

The statewide snowpack’s water content in April was below historical average at 87 percent, giving little hope that California would rebound from its devastating drought, now in its fifth year.

This year, there are areas in Northern California that are showing precipitation measurements of a “normal” year. Unfortunately, the anticipated El Niño drenching, especially in Southern California, did not materialize as hoped. The numbers in the south speak for themselves, yet Rizzardo cautioned about reading too much into the “nearly normal” tallies found in the north.

“You think almost normal is close to 100 percent, and that’s good. But it’s not 100 percent. Less than that means we are in a deficit,” he said. And that means less water supply in summer months.

DWR posts snowpack data in Bulletin

120, issued in the second week of February, March, April and

May. Not just for weather geeks and water wonks, the publication

is a wealth of information containing forecasts of how much

runoff will occur from the state’s major watersheds, along with

summaries of precipitation, snowpack, reservoir storage and

runoff in various regions of the state.

DWR posts snowpack data in Bulletin

120, issued in the second week of February, March, April and

May. Not just for weather geeks and water wonks, the publication

is a wealth of information containing forecasts of how much

runoff will occur from the state’s major watersheds, along with

summaries of precipitation, snowpack, reservoir storage and

runoff in various regions of the state.