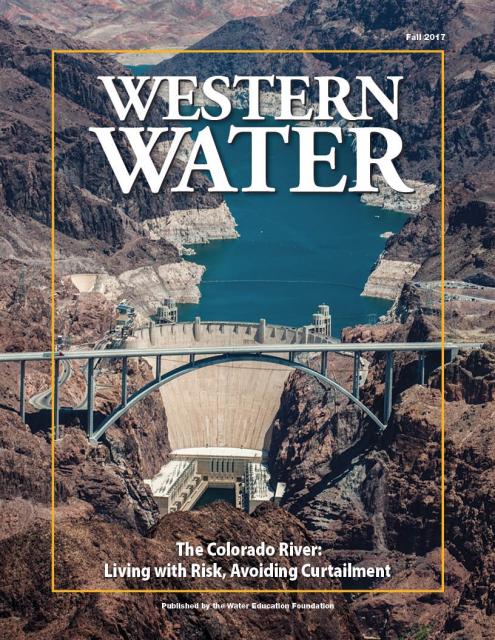

The Colorado River: Living with Risk, Avoiding Curtailment

Fall 2017

There is a timelessness to the Colorado River as it makes its ancient run from the headwaters in the Upper Basin through the arid Lower Basin states and to the farm fields, wildlife habitat and urban environment that make up the Southwest.

There also is a sense of urgency regarding how an overallocated river is managed for its many competing uses in the face of looming shortages and a grim climate change forecast that predicts much less river flow in the years to come.

Read the excerpt below from the Fall 2017 issue written by Gary Pitzer along with the editor’s note from Jennifer Bowles. Click here to explore more excerpts from Western Water, the foundation’s quarterly magazine.

Introduction

There is a timelessness to the Colorado River as it makes its ancient run from the headwaters in the Upper Basin through the arid Lower Basin states and to the farm fields, wildlife habitat and urban environment that make up the Southwest.

There also is a sense of urgency regarding how an overallocated river is managed for its many competing uses in the face of looming shortages and a grim climate change forecast that predicts much less river flow in the years to come.

People who have dealt with river management issues for decades are girding for a heightened degree of activity that calls upon years of trust and collaboration to compose a plan for equitably sharing a vital resource.

The alternative, it’s said, is an undesirable outcome that sends the available water to the places that can afford to pay the most for it.

“If the system crashes, there will be winners and losers, and I believe the biggest losers will be agriculture and the environment,” said Ted Kowalski, senior program officer with the Walton Family Foundation at the Water Education Foundation’s invitation-only Colorado River Symposium, held in late September in Santa Fe, N.M. “We need to start thinking about it now, because if we end up in interstate litigation or in front of the Supreme Court or if there are front-page stories about the Southwest running out of water, it damages our economies, it damages all of what we have worked for and really damages our entire community, from the U.S. down to Mexico.”

Kowalski is a veteran of Colorado River policy issues having spent time with the Colorado Attorney General’s office working on water rights and later the Colorado Water Conservation Board working on instream flow issues and interstate issues. Before moving to the Walton Family Foundation, he was a senior negotiator on federal, interstate and international issues related to the Colorado River.

Major water suppliers in the Lower Basin from Arizona, California and Nevada are working on the terms of a Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) that would overlie the existing shortage criteria in the 2007 Interim Guidelines. The 2007 Interim Guidelines were enacted in part to determine who gets what level of shortages based on elevations in Lake Mead. The first shortage trigger occurs when Lake Mead falls below 1,075 feet above sea level by the end of any year.

Kowalski likened completion of the DCP to the moving of a heavy rock and the need to not drop it.

“We don’t have a specific backstop and I’m worried we don’t have the strong sense of urgency that we need,” he said. The year 2018 “is the right year to keep up that momentum and we need to keep lifting that rock.”

Unprecedented drought in the Colorado River Basin resulted in the 2007 Interim Guidelines, which include a milestone shortage sharing agreement in the Lower Basin and provisions for intentionally created surplus (ICS) in Lake Mead.

After a decade of living with shortage criteria under the 2007 Guidelines, there is momentum in advance of negotiating the next round of shortage sharing and ICS criteria.

“We will need a broader, more flexible ICS in Lake Mead and broader trading arrangements,” said Anne Castle, senior fellow at the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy and the Environment. Castle served as assistant secretary for water and science at the U.S. Department of the Interior (Interior) from 2009 to 2014. “It will require a lot more creative thinking ahead of the reconsultation for the next set of operational guidelines.”

It also will take financial contributions from the federal government and water users as a down payment for ensuring a measure of stability and sustainability on the river.

Today’s increased sense of sharing the resource extends to American Indian tribes and their need to pursue and receive their water entitlements. “It is important from an equitable standpoint to settle Indian water rights claims,” said Mike Connor, former Interior deputy secretary during the Obama Administration. “All of these agreements are intended to bring more reliability and less uncertainty to the system.”

Margaret Vick, special counsel for the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT), said there are barriers between Indian water rights claims and the actual allocation of a supply.

“The biggest issue with decreed water rights is if you have a decree, you don’t have a settlement,” she said. “If you don’t have a settlement, you don’t have the flexibility in the way you can use that water.”

Composed of the Mohave, Chemehuevi, Hopi and Navajo tribes, CRIT has more than 4,200 active members on 300,000 acres of land on the California and Arizona sides of the Colorado River.

Darryl Vigil, water administrator for the Jicarilla Apache Nation in New Mexico, said 2.4 million acre-feet are available to tribes in the Upper and Lower basins, “which is absolutely substantial in terms of being a major stakeholder of water in the Colorado River.”

The Jicarilla are part of the Ten Tribes Partnership that leapt into action because of its perceived “exclusion” from the Bureau of Reclamation’s (Reclamation) 2012 Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study (Basin Study), Vigil said. That concern led to the initiation of the Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Tribal Water Study (Tribal Water Study) that will include details of each settlement and decree, what happens with full development and how it impacts the rest of the Basin.

“We see the Tribal Water Study as the platform and the foundation and a jumping-off point for us to really get into the process,” Vigil said. “How do we move this? Is it legislation, litigation or collaboration? Obviously, our preference is collaboration.” But he cautioned that each tribe has different rights, interests and goals and that the other stakeholders need to keep that in mind.

At the Symposium, officials from the United States and Mexican governments celebrated implementing an agreement to the 1944 Water Treaty between the two countries called Minute 323. The Minute essentially extended 2012’s Minute 319 that gave Mexico greater flexibility in managing its Colorado River allotment, which provides mechanisms for increased conservation and water storage in Lake Mead elevation to help offset the impacts of drought and prevent a shortage from being triggered.

“This agreement provides certainty for water operations in both countries and mainly establishes a planning tool that allows Mexico to define the most suitable actions for managing its Colorado River waters allotted by the 1944 Water Treaty,” said Roberto Salmón, the Mexican commissioner of the International Boundary and Water Commission.

Carlos de la Parra, professor and researcher at the Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana, said Minute 323 reflects the improved climate of trust and understanding.

“Prior to this, the negotiations were a bilateral process with both countries looking out for themselves,” he said. “The U.S. and Mexico were in an adversarial relationship that has melted before our eyes. It’s now about regional water management when it comes to the Colorado River. Mexico no longer considers itself a victim of manipulation and the partnership is gelling.”

An overarching message from the Symposium, “Taking Action on the Colorado River: Are We Up to the Challenge?,” was that the agreements reached beginning in the early 2000s through the 2012 Basin Study need to be followed up with more action.

Jim Lochhead, chief executive officer and general manager of Denver Water, said it’s crucial that stakeholders not rest on their laurels and expect the upcoming winter to adequately replenish the snowpack. The river has been in a drought since 2000.

“This river is not in good shape today, despite the fact we have made progress and despite the fact this year was a somewhat normal year,” he said. “We are at a tipping point where we can achieve another spectacular success, or we can fail miserably if we don’t pull the pieces together and the pieces are sitting, frankly, right in front of all of us.”

The history of the Colorado River is full of conflict, compromise and resolution regarding water use, from the 1922 Colorado River Compact to the momentous 1964 Supreme Court decision in Arizona v. California. More recently, the Palo Verde Irrigation District sued Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD) because of issues related to MWD’s purchase of farmland in Palo Verde so that some Colorado River water could be moved to urban Southern California.

Despite the disputes, people from Wyoming to Mexico realize that it often takes detailed funding agreements to make water available to regions when it’s needed for a specific purpose.

“Conservation-wise, solutions that make economic sense will stand the test of time and so we believe strongly in markets markets by themselves won’t be a panacea,” Kowalski said.

Ever-increasing and detailed study results data are pointing to a dramatically altered hydrologic future on the river, one that portends a new reality that will require the most stringent of drought contingency planning and most likely a change in water use practices.

Leading climate change scientist Brad Udall with the Colorado Water Institute told Symposium attendees that everyone must up their game to do more with less.

“Despite all the great work that’s been done on drought contingency planning, this Basin is not doing enough to deal with the risk,” he said. “We can adapt, we can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and to the extent we do neither we will suffer.” Udall’s 2017 report, co-authored with Jonathan Overpeck, The 21st Century Colorado River: Hot Drought and Implications for the Future, said the period of drought from 2000 to 2014 was the worst 15-year drought since 1906 and that increased temperatures sparked by climate change are causing “hot droughts” that diminish the river’s flow.

“These results, combined with the increasing likelihood of prolonged drought in the river Basin, suggest that future climate change impacts on the Colorado River flows will be much more serious than currently assumed, especially if substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions do not occur,” the report said.

Udall acknowledged the thorny issue of perhaps reallocating or redistributing water in a Basin where the Law of the River is sacrosanct.

“Most people in this community have shied away from promoting greenhouse gas reductions, thinking it’s too politically sensitive, that it’s somebody else’s problem,” he said. “Greenhouse gas reductions are everyone’s problem. We have the policy tools and the technology to begin solving this meaningfully.” Colorado River water users are acutely aware of the precarious situation, having spent the last several years going to extraordinary measures to prevent Lake Mead from dropping low enough to trigger the shortage declaration in the Lower Basin – the official process by which the first round of reduced water deliveries would occur for Arizona and Nevada.

Under the terms of the DCP, the Lower Basin states, U.S. and Mexico are required to put water in Lake Mead or reduce deliveries at certain triggers, with each state subject to a different trigger. In an interview, Bill Hasencamp, manager of Colorado River resources for MWD (a signatory to the DCP), said the DCP “provides flexibility” for water users to take ICS water from Lake Mead.

As would be expected, forging the means of taking voluntary cuts is a controversial issue and there remains the question of when such a deal can be made, given the political vagaries associated with Colorado River water use, one of which is approval of the DCP by the Arizona Legislature.

Hasencamp said “we haven’t gotten to the point of ultimatums yet,” and that the idea is to have a completed DCP by next summer in time for the 2019 Annual Operating Plan for the river.

Completion of the DCP is critical because Minute 323’s binational water scarcity contingency plan between the two countries is contingent on the Upper Basin and Lower Basin states ratifying their own DCP agreements.

The Minute has two separate sections related to shortage and drought. There is one section that requires Mexico to take shortages when Lake Mead drops to 1,075 feet above sea level that tracks the Lower Basin shortages under the 2007 Guidelines. That is the shortage-sharing part of the Minute and that became effective on Sept. 27.

The Minute’s Binational Water Scarcity Contingency Plan (BWSCP) has certain reductions applicable to Mexico but only if the Lower Basin adopts a DCP.

Upper Basin water use in the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming is overseen by an interstate commission that is working on a suite of actions designed to create a form of water banking while honing a system to shepherd water to Lake Powell to comply with the Colorado River Compact, which requires a flow at Lee Ferry of not less than 75 million acre-feet during any period of 10 consecutive years. The parameters differ from the Lower Basin, where the Secretary of the Interior serves as the watermaster responsible for distributing all Colorado River water below Hoover Dam.

“From an Upper Basin perspective, we need assistance from Interior and the Lower Basin states to recognize the complexities and help move us forward,” Lochhead said.

In the Lower Basin, where water rights are fiercely guarded, forging a voluntary agreement among large water supply entities is a tricky enterprise infused with political ramifications, not the least of which is California’s first priority to Colorado River water.

Arizona, the junior user, has the most at risk in terms of shortage and must carefully craft its approach to voluntary use reductions.

“Within Arizona, it is the issues regarding the impacts to various water user groups – homebuilders and developers, agricultural tribes and cities – who are all disproportionately impacted by the additional reductions that will occur in Arizona,” Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke said at the Symposium.

Those issues will have to be resolved before the state finalizes a deal with California and Nevada.

Editor’s Note: Cooperation Over Conflict

International sharing of rivers and lakes has always intrigued me. Perhaps it’s because I was born on the edge of Lake Ontario, one of five Great Lakes shared between the U.S. and Canada, driving the imagination of a youngster about what and who was on the other side.

In California, we share a handful of major rivers with other states, including the Truckee, Carson and Walker rivers with Nevada and the Klamath with Oregon. But perhaps none are as storied and historic as the mighty Colorado River that California shares with six other Western states and Mexico. The lifeblood of the Southwest, some 40 million residents depend on it.

Earlier this year, in the waning hours of the Obama administration, the U.S. and Mexican governments failed to reach their latest agreement on the river, as hoped for. The lack of agreement caused concern because they were so close and with any change of administrations – whether the same political party or not – the process could be delayed even more.

But, after two years of negotiations, agreement between the two countries was indeed reached. And it was an honor to have representatives from both countries put their final signatures to paper, placing the agreement – known as Minute 323 – into full force and effect at our biennial Colorado River Symposium in Santa Fe in late September. You can read more details about Minute 323 in this issue of Western Water.

Suffice it to say, the New Mexican capital plays an important role in milestones for the river. It was here that the 1922 Compact dividing the river between the seven U.S. states was negotiated and signed.

“It’s a beautiful day in Santa Fe,” Edward Drusina, the U.S. Commissioner of the International Boundary and Water Commission, said in announcing Minute 323, a new agreement to the 1944 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty. “For generations water scarcity and drought in the West has translated into conflict. I’m proud that our countries’ water leaders have chosen cooperation over conflict here in the Colorado River Basin.”

Roberto Salmón, Drusina’s Mexican counterpart, signed his letter and ended his speech with this: “Having a guide or map of what to do and how to do it is our responsibility to future generations. It can’t be said that our generation sat with our arms crossed.”

And there was the answer to my childhood question of who was on

the other side: People who care just as much about the water.