The Delta at a Crossroads

Spring 2016

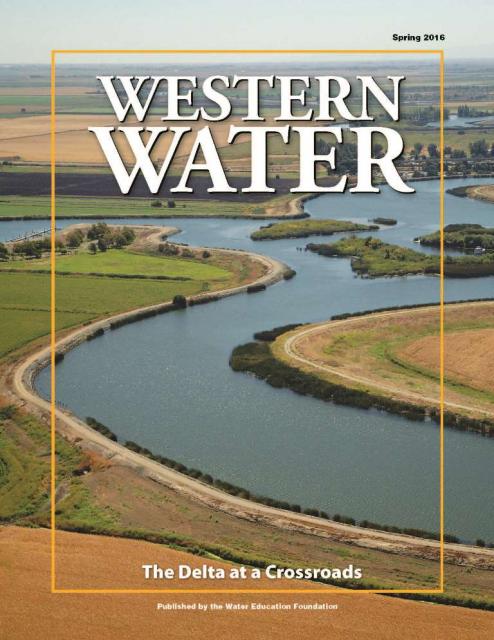

Many Californians are not aware of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta but its significance to the state’s water supply picture has never been more magnified. A transformed region of sunken islands and crisscrossed sloughs and channels protected by earthen levees that perform more like dams, the Delta is the hub of the state’s water system.

It is in this maze of islands where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers meet just south of Sacramento and north of Stockton. As water enters the Delta some of it flows into San Francisco Bay, while some is pumped out of the Delta and transported hundreds of miles to homes in the Bay Area and Southern California and to farm fields in the San Joaquin Valley via the State Water Project (SWP) and the federal Central Valley Project (CVP).

It is this conveyance of water to the projects’ export pumps at the south end of the Delta that is a problem because operation of the pumping plants can kill fish, including the endangered Delta smelt and winter-run Chinook salmon, that are drawn into the pumps. The strength of the apparatus also can cause reverse flows in some places. Water quality, high salt in particular, also is a concern for fish and farmers alike in the Delta.

After decades of trying to resolve the problem, the state of California and the federal government are pursuing the California WaterFix, a $15 billion plan that would be a major re-working of the Delta plumbing system. At its heart are three intakes in the northern Delta on the Sacramento River that would feed twin tunnels – 40 feet wide, 39 miles long and 150 feet underground. The tunnels would transport water under the Delta to the existing state and federal pumping facilities in the southern Delta near Tracy.

Read the excerpt below from the Spring 2016 issue written by Gary Pitzer along with the editor’s note from Jennifer Bowles. Click here to subscribe to Western Water and get full access via a digital or print publication.

Introduction

Many Californians are not aware of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta but its significance to the state’s water supply picture has never been more magnified. A transformed region of sunken islands and crisscrossed sloughs and channels protected by earthen levees that perform more like dams, the Delta is the hub of the state’s water system.

It is in this maze of islands where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers meet just south of Sacramento and north of Stockton. As water enters the Delta some of it flows into San Francisco Bay, while some is pumped out of the Delta and transported hundreds of miles to homes in the Bay Area and Southern California and to farm fields in the San Joaquin Valley via the State Water Project (SWP) and the federal Central Valley Project (CVP).

It is this conveyance of water to the projects’ export pumps at the south end of the Delta that is a problem because operation of the pumping plants can kill fish, including the endangered Delta smelt and winter-run Chinook salmon, that are drawn into the pumps. The strength of the apparatus also can cause reverse flows in some places. Water quality, high salt in particular, also is a concern for fish and farmers alike in the Delta.

After decades of trying to resolve the problem, the state of California and the federal government are pursuing the California WaterFix, a $15 billion plan that would be a major re-working of the Delta plumbing system. At its heart are three intakes in the northern Delta on the Sacramento River that would feed twin tunnels – 40 feet wide, 39 miles long and 150 feet underground. The tunnels would transport water under the Delta to the existing state and federal pumping facilities in the southern Delta near Tracy.

The intakes/tunnels are being proposed as a way to capture more water during winter storms when runoff from the rivers that feed into the Delta is high and reduce pumping when inflow is low to maintain habitat and water quality. Proponents say it will resolve the chronic interruptions in pumping that occur because of the need to protect the fish.

In a February op-ed published in The Sacramento Bee, California Resources Secretary John Laird wrote that the tunnels are necessary for years like this, when high flows prompted by El Niño rains could be safely pumped from the Delta.

According to the Natural Resources Agency, 486,000 acre-feet of water could have been diverted between January and March alone because of high river flows that cannot be captured by the existing pumping facilities because of environmental constraints.

“Despite the volatility of California’s winters, it’s believed the WaterFix could increase [annual] yield by roughly an additional 200,000 acre-feet on average,” said Nancy Vogel, deputy secretary for communications with the Resources Agency. She noted that the project’s value “is ensuring the baseline amount won’t be further eroded.”

Opponents of the plan are concerned that taking water directly from the Sacramento River, rather than after it flows through the Delta, will be detrimental to Delta water quality because there will be less fresh water keeping salty water at bay in the estuary; a concern held by the people who live in the Delta.

“It’s viewed by many as an existential threat to the Delta,” Erik Vink, executive director of the Delta Protection Commission, said at the Water Education Foundation’s March 17 Executive Briefing. “That’s really the clear, strong feeling coming from the Delta region.”

In an October 2015 comment letter about the project, the Delta Protection Commission –which includes local government representatives from Contra Costa, Sacramento, San Joaquin, Solano and Yolo counties – wrote that the WaterFix “would fundamentally change the agricultural- and water-based character of Delta communities and landscape because of the many impacts that could not possibly be mitigated.”

The project’s 2015 environmental impact report (EIR) acknowledged that “water quality is an issue of concern because of uncertainties regarding activities associated with conveyance facilities and restored habitat that could lead to discharge of sediment, possible changes in salinity patterns, and water quality changes that could result from modifications to existing flow regimes.”

The EIR noted that the WaterFix’s dual conveyance system “would align water operations to better reflect natural seasonal flow patterns” while reducing “the ongoing physical impacts associated with sole reliance on the southern diversion facilities and allowing for greater operational flexibility to better protect fish.”

Minimizing south Delta pumping “would provide more natural east-west flow patterns. The new diversions would also help protect critical water supplies against the threats of sea level rise and earthquakes,” the EIR said, about the tunnels.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) supports the idea of alternative conveyance but not the iteration proposed in the WaterFix.

“NRDC believes that new conveyance, if properly sited and operated, could be part of a solution for restoring the Delta ecosystem but the current proposed project is going to worsen conditions for fish and wildlife and communities in the Delta,” said Doug Obegi, senior attorney with NRDC’s water program. “It proposes to take even more water out of the estuary even though the best available science shows we need to reduce diversions and it’s now state policy to do so.”

Some of those receiving water from the Delta want more details about the WaterFix.

“We have been studying this iteration of isolated conveyance facilities in the Delta for 10 years and we still don’t have a good understanding of how much water those facilities will be able to move and the cost of those facilities,” said Tom Birmingham, general manager of Westlands Water District, the largest agricultural water district in the United States. Westlands is the largest CVP contractor and would help finance construction of the tunnels portion of the WaterFix. Birmingham voiced support of the project in a 2014 WaterFix Policy Paper.

Placing new intakes on the Sacramento River means what could be a lengthy adjudicatory hearing process before the State Water Resources Control Board (State Water Board). The State Water Board will consider the addition of three new points of diversion and/or points of rediversion of water to specified water right permits for the SWP and CVP and to ensure no harm is done to other water rights holders or the environment by the tunnels. Originally, the hearing was to start in the spring but was postponed until the end of June. The water rights hearing process could take as long as two years to complete.

More than 23 million people get at least a portion of their drinking water from the SWP or CVP. Both projects provide water to the Silicon Valley via the Santa Clara Valley Water District. Fifty-five percent of Santa Clara County’s water is imported and 40 percent of that comes through the Delta. Barbara Keegan, chair of the Santa Clara Valley Water District board of directors, called the WaterFix “buildable and feasible” but said she recognizes the important role flows play in the Bay-Delta Estuary.

“There’s a perception by some that any water that flows through the Delta into Suisun Bay, San Pablo Bay and San Francisco Bay and then out to the ocean is wasted water and I don’t necessarily agree with that,” she said. “There may be benefits that we are not clearly aware of.”

The dilemma of balancing needs for the economy and the environment in the Delta and the importance of transporting water from where it occurs to where it is needed is at the heart of the debate over the Delta and water conveyance.

It’s a situation that has vexed a generation of people trying to find a solution to the turmoil.

“The Delta has the geographic misfortune of being at the center of California’s water supply system,” said Jay Lund, director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California, Davis. He spoke April 28 at the Capitol Weekly’s Water: 2016 conference in Sacramento.

While the debate over Delta conveyance is not new, a number of combined factors have made it a current headline issue: Gov. Jerry Brown’s resolve to construct the tunnels, proposed legislation that would require ballot-box approval, the pending water rights hearing for the tunnels’ intake and water users’ frustration over reduced Delta exports despite the improved precipitation in early 2016 following several years of drought.

By Gary Pitzer

Editor’s Note: Plying California’s Most Political Waters

Having lived in Southern California for several years, I always knew the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta existed and the pivotal role it plays in California water. As a reporter, I visited the Delta a couple times during fellowships for a few hours here and there, and I keenly studied maps to understand how water flows through it.

But I never got to really know the Delta and its maze of islands, canals and levees until I moved to Sacramento in 2014. Now it’s become a unique place to take friends and relatives when they visit, to drive along the levees that separate the massive Sacramento River from vineyards and vegetable fields, and the historic and quaint towns.

The Delta tunnels projects, known by its proponents as California WaterFix, is controversial in some circles and there’s no doubt that it’s a costly undertaking. The next year could prove crucial as regulators begin the process on whether to approve new diversion points off the Sacramento River for the intakes to the tunnels, the fishery agencies determine the biological implications of the project and the water agencies decide how to fund it.

At the Foundation, staying impartial is key to our mission. We don’t take a side on this project either way. We hope that, in writing this issue on the Delta tunnels, we lay out the arguments on all sides as a way of contributing to the ongoing discussions revolving around the key natural resource.

As I write this, the Foundation is gearing up for its annual Bay-Delta Tour June 15-17. It’s our only two-bus tour of the year and it’s nearly sold out. Perhaps that is indicative of the interest in this tunnels project, and the key role that the Delta plays in California water.

We hope we’ve done our duty well in spelling out the issues. As always, don’t hesitate to let us know.