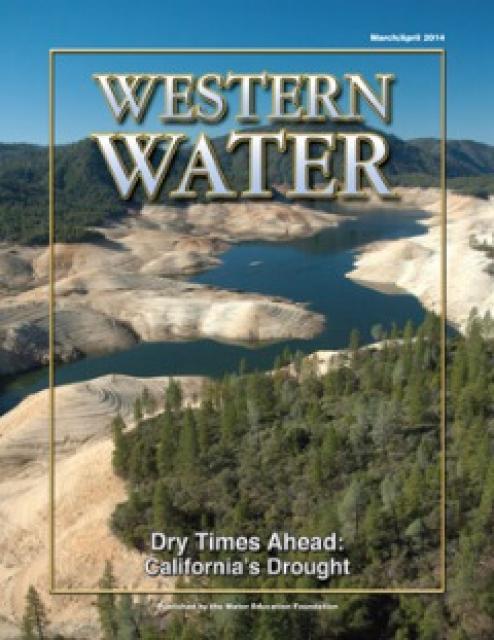

Dry Times Ahead: California’s Drought

March/April 2014

Living in the semi-arid, Mediterranean climate of California, drought always lingers on the horizon. People believe they are ready to face the next dry period, then conditions arrive testing whether that is the case.

Introduction

The last 18 months or so have been marked by dryness that, while not unprecedented, tests the state’s resiliency. California had its warmest and third driest winter on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Climatic Data Center.

Late winter rains notwithstanding, the dryness harkens to the record drought of 1976-1977, considered the modern benchmark of California drought. Craig Wilson, Delta watermaster for the State Water Resources Control Board (State Water Board) was staff counsel back then. He told board members in February that 2014 is worse than what occurred nearly 40 years ago.

“We have a heck of a lot more people and on the environmental side, there is an environmental component that wasn’t there,” he said.

The drought’s reverberations are felt all the way in Washington, D.C. President Barack Obama visited the Central Valley for the first time Feb. 14 to evaluate the crisis.

“Droughts have obviously been part of life out here in the West since before any of us were around,” he said. “Water politics in California have always been complicated.”

In pledging a $183 million relief package, the president steered clear of the divisions that exist in California water policy, namely the demand that environmental restrictions be eased to allow more water to flow to parched farms. Writing in the Fresno Bee the day after Obama’s visit, Don Peracchi, president of Westlands Water District Board of Directors, blamed government mismanagement of water for the region’s woes and that “the layer upon layer of regulations which have created priority requirements for the environment have caused chronic shortage of water for human use.”

The drought has exposed the raw, sometimes acrimonious emotions associated with a water delivery system that is strained to provide for all the needs placed on it. The zero percent allocation declarations for certain service areas of the State Water Project (SWP) and federal Central Valley Project (CVP) and the 40 percent allocation for settlement and exchange contractors have left water users in a tough place while prompting a call for action by some in congress.

In March, 13 congressional Republicans from the San Joaquin Valley and Southern California wrote to the president and Gov. Jerry Brown, asking them to “stop the loss of tens of thousands of acre-feet of water into the Pacific Ocean that otherwise could have been sent to drought-stricken communities.”

The letter charges federal and state agencies with “regulatory inflexibility” that has “compounded the current drought’s impacts” on water users south of the Delta. Furthermore, pumping has been hampered even when water is available because “regulators continue to prioritize it for fish.”

Others in Congress are using the drought as an opportunity to move new starge projects forward. In March, Reps. Doug LaMalfa, R-Richvale, and John Garamendi, D-Walnut Grove, announced the Sacramento Valley Water Storage and Restoration Act of 2014, which would authorize construction of Sites Reservoir in Colusa County if it is deemed feasible.

On the drawing board for about 30 years, Sites Reservoir would hold about 2 million acre-feet of water diverted from the Sacramento River during high flows. LaMalfa said “it’s time to end the decade of studies and build this project” before the next drought hits the state.

A bump in rainfall enabled the department of Water Resources (DWR) and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) to slightly increase deliveries to farmers, though the dry conditions necessitated the agencies to ask the State Water Board to allow them to retain water in reservoirs instead of releasing it to maintain Delta salinity standards. Under normal circumstances, an outflow of 11,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) would become effective April 1. Instead, the rate will be 7,100 cfs.

The Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), which manages Folsom Lake, part of the CVP, says many factors are part of management decisions, including obligations to contractors, flood management, fishery requirements and Delta freshwater needs. The agency had to release water in 2013 with the expectation that replenishment would arrive in 2014.

The dry conditions have prompted revival of the axiom of never letting a good crisis go to waste when it comes to evaluating the assumptions supply and use. “We’ve got to go back to the assumptions of climate and precipitation that are written into the foundational principles of water contracts, water rights and operational agreements,” said Phil Isenberg, vice chair of the Delta Stewardship Council.

After the president announced the federal government’s help, Gov. Jerry Brown and legislative leaders unveiled a $687 million relief package, $549 million of which stems from available bond money from Propositions 84 and 1E. Meanwhile, there are a host of water bond proposals in the Legislature that aim to generate funds for new water storage projects.

An $11 billion bond is slated for the November ballot, but legislators have several bond packages to consider, leaving it unclear which – if any – bond will be on a ballot – and when.

The drought is prompting questions of its origins, given the typically variable weather conditions that characterize California’s climate. Scientists say the dry conditions in California are part of a worldwide weather pattern with a cause and effect that stretches far beyond the state’s shores.

“The drought in California didn’t start in California,” said Kelly Redmond, regional climatologist with the Desert Research Institute, at the California Drought Outlook Forum Feb. 20 in Sacramento. “It is caused by global conditions.”

The drought reminds people of the extreme variability that characterizes the state’s weather and that counting on a “normal” year comes at a risk.

More than 100 years of records indicate that California rainy seasons are below historical average 60 percent of the time, said Martin Hoerling, research meteorologist with NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory, at the Drought Forum. As for the current drought, “some of it is weather, some of it is caused by ocean conditions,” he said.

Late winter rains notwithstanding, the drought of 2014 is an extension of a string of below-normal water years dating to 2007. Indeed 2013 was notoriously dry, as evidenced by the city of Los Angeles’ 3.60 inches of rain, making it the driest calendar year since recordkeeping began in July of 1877. The city averages about 15 inches of rain in a calendar year. Sacramento set a record for consecutive dry days while some rural areas saw their water supplies drop to critically low levels.

California receives most of its rain and snow in December, January and February. As a dry December lingered into a very dry January, state officials acted quickly once the scale of the coming hardship loomed. On Jan. 31, Reclamation, DWR and the State Water Board ordered all but the most needed water supplies to be held in reservoirs while telling those with diversion rights to be ready to cutback use.

“These actions are largely unprecedented but also unavoidable,” DWR Director Mark Cowin told reporters in Sacramento.

The order to retain water in reservoirs caused friction because of Southern California’s relatively better position, water supply-wise. Accusations have flared that officials exported water in 2013 despite the dry conditions, leaving sites like Folsom Lake dangerously close to dead pool status before rebounding somewhat.

“The projects operate on a year to year basis with little thought of tomorrow,” Chris Shutes with the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance told the State Water Board Feb. 18.

Officials with DWR and Reclamation say water deliveries in 2013 were in accordance with contract commitments and the need to provide necessary flow requirements for fish and freshwater. Furthermore, the absolute lack of rain in December and January was beyond anyone’s ability to predict. The order to limit Delta outflow can be amended “on an ongoing basis,” said Tom Howard, executive director of the State Water Board.

The State Water Board told its riparian water rights holders that if they are in a water-short area, they “should be looking into alternative water supplies” such as groundwater, purchased water and recycled wastewater. Water right holders are cautioned that groundwater resources are significantly depleted in some areas. Water right holders in these areas should make planting and other decisions accordingly. The notices of possible curtailment initially have been sent to water rights holders statewide.

Wilson told the Delta Stewardship Council in January that “in drought circumstances like this, what could have been a reasonable method of diversion in times of plenty might not be considered reasonable now.”

Following the announced cutbacks, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD), declared a water supply alert, urging users throughout the region “to achieve extraordinary conservation.” MWD, the nation’s largest supplier of treated water, doubled its annual conservation and outreach budget from $20 million to $40 million, with the extra funds going toward additional rebate incentives for people to buy water-saving devices.

The drought has amplified efforts to improve weather forecasting to better warn people of impending dryness. The current official outlook is prepared by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center at lengths extending to 90 days and beyond at a national scale, “but the problem is the skill is very low,” said Jeanine Jones, deputy drought manager with DWR.

Long-term research to improve forecasting is needed but “in the near term we need to look at other tools and any other bits and pieces of information that we can glean to improve forecast skill at regional geographic scales – the low hanging fruit – that we can cut and paste together and see if it helps,” Jones said.

Jones said it is people such as Duane Waliser, chief scientist of the Earth Science and Technology Directorate at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, who are working to improve the collective knowledge of how global weather and climate processes affect California.

“At the shorter time scale, forecasters are working to understand the mechanics of the complex atmospheric phenomena better to enable agencies such as DWR to have a better handle on what to expect within a given season,” Waliser said in an interview.

Response to the drought is being wrangled in Congress, with Republicans representing the hard-hit areas getting behind a measure that get more water to their constituents. Their bill, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Valley Emergency Water Delivery Act, would among other things, permanently overturn the San Joaquin River Restoration Act. The bill’s lead author is Rep. David Valadao of Hanford.

The bill is opposed by Gov. Jerry Brown, who said it was “unwelcome and intrusive,” and “falsely suggests the promise of water relief when that is simply not possible given the scarcity of water supplies.”

Sen. Feinstein in February introduced the California Emergency Drought Relief Act of 2014, which among other things requires federal agencies “to maximize water supplies, reduce project review times and ensure water is directed to users whose need is greatest.” The bill includes $25 million to provide safe drinking water in vulnerable communities.

Aside from the political response to the drought is the genuine belief that California can go much farther in stretching the water supply it already has.

“New water supply for California’s 38 million residents is actually close at hand, if we take a harder look at the water that communities already use,” according to Cynthia Koehler, Kathleen Moazed and Audrey Finci, the co-founders of WaterNow, a nonprofit that promotes “sustainable community level water solutions.”

In a Jan.29 opinion piece, the three principals wrote there is a “major potential to tap the huge quantities of water that urban Californians apply to their outdoor greenery,” and other techniques such as drought resistant landscaping and re-use of graywater “that could provide significant benefits almost immediately.”

They also took the opportunity to echo the refrain that there is much to be gained in cracking down on outdoor water use.

“The state’s 12 million households account for about two-thirds of total urban consumption, and most of this water is devoted to outdoor use – not drinking or cooking or laundry or even the extraordinarily long showers taken by our teenage children. Estimates vary from 53 percent to 65 percent, but on average we are sprinkling the largest proportion of our drinking water on sidewalks, lawns and gardens.”

Meanwhile, while California’s people struggle with the impacts of the drought, California’s native fish, many species of which are on the brink of extinction, will find survival doubly difficult with stream and river flows diminished to a trickle.

“It will be a lousy place for salmon, no matter what,” said Peter Moyle, fish biologist at the University of California, Davis. Those conditions will challenge agency managers to prevent salmon runs from being wiped out, as required by federal and state endangered species laws, which “essentially say it is the policy of the United States and California to not let species go extinct.”

This issue of Western Water looks at the 2014 drought, which is shaping up to be one of the worst in California’s recorded history.

Click here to purchase a copy of the entire article.

Editor’s Desk

It’s been almost 35 years since I walked in the door of the Foundation as the executive director. The water picture in California and the West has changed a lot in that time. In 1980, California was still reeling from the 1976-77 severe drought. Farmers were being criticized for growing low value crops with subsidized water. Environmentalists were trying to find public support for saving Mono Lake and obtaining more water in streams for fish. Cities were beginning to think about water conservation as part of their portfolio. And the fight over building new dams and conveyance was on.

Today as I leave my position, much progress has been made in those three sectors that fight most about water. For better or worse, farmers no longer have low cost water and generally have greatly increased their efficiency. Environmentalists have won major court battles to get more water for fish and restrict the state and federal water projects pumping. Court reinforcement of the public trust doctrine saved Mono Lake. And the urban users – in most cases – are committed to water use efficiency through lots of innovative programs. Generally, progress has been made in areas of water pricing, conservation, transfers and flood management.

However, there is no doubt that the way we manage water in California and the West often is through a silo approach. Increasingly many stakeholders agree that local, state and federal systems need more integration and flexibility. And that includes managing groundwater and surface water together.

Now it’s time for me to spend some more time with family and friends. I’ll remain a senior advisor to the Foundation. In the meantime, the Water Education Foundation will be in good hands with the selection of the new executive director, Jennifer Bowles. Jennifer’s experience includes nine years with Associated Press as a reporter and supervising editor, another nine years as the environmental reporter for the Riverside Press Enterprise and five years as the communications strategist on natural resource issues at the law firm of Best Best & Krieger in Riverside, California. She comes to us with the journalistic integrity and marketing ability to take the Foundations to new levels of water communication and education. And the irreplaceable Sue McClurg now becomes the Foundation’s deputy executive director.

Thanks for your support through the years. The job of water education continues and we look to your support in the future.