Historic Drought and the Colorado River: Today and Tomorrow

November/December 2015

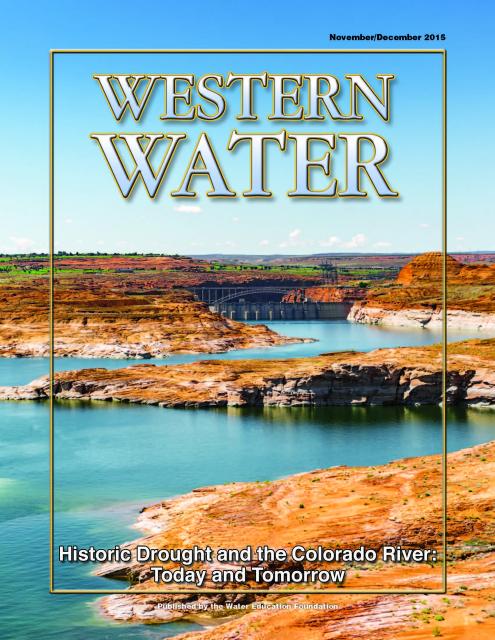

The dramatic decline in water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell is perhaps the most visible sign of the historic drought that has gripped the Colorado River Basin for the past 16 years. In 2000, the reservoirs stood at nearly 100 percent capacity; today, Lake Powell is at 49 percent capacity while Lake Mead has dropped to 38 percent. Before the late season runoff of Miracle May, it looked as if Mead might drop low enough to trigger the first-ever Lower Basin shortage determination in 2016.

Read the excerpt below from the Sept./Oct. 2015 issue along with the editor’s note. Click here to subscribe to Western Water and get full access.

Introduction

The dramatic decline in water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell is perhaps the most visible sign of the historic drought that has gripped the Colorado River Basin for the past 16 years. In 2000, the reservoirs stood at nearly 100 percent capacity; today, Lake Powell is at 49 percent capacity while Lake Mead has dropped to 38 percent. Before the late season runoff of Miracle May, it looked as if Mead might drop low enough to trigger the first-ever Lower Basin shortage determination in 2016.

The higher than anticipated inflows into Lake Powell resulted in a 9 million acre-feet annual release from Lake Powell, slowing Lake Mead’s declines and pushing back the potential for a Lower Basin shortage until 2017, alleviating the immediate crisis. But the risk remains, especially for Arizona and Nevada, which would see the first cutbacks in water deliveries in a shortage condition.

“All the individual efforts to keep water in Lake Mead and a little help from Mother Nature is what has resulted in us not having a shortage in 2016 because we expect to be about 7 feet above that first shortage level of [elevation] 1075,” said Ted Cooke, interim general manager of the Central Arizona Project (CAP). But, he added, “We are hurtling toward those shortage levels. … That’s a message to me that while the short-term incremental things we’re doing are important – they’re essential or we wouldn’t have accomplished what we have – we need something bigger. We need something that lasts longer.”

And even though there will not be a shortage determination in 2016, there remains an 18 percent probability of one in 2017. The Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) has projected that Mead’s elevation will be 1,082 feet on Jan. 1, 2016 under the most probable inflow scenario. (The first shortage trigger is elevation 1,075 feet.) Thus, no shortage is anticipated for calendar year 2016.

Noting that the unexpected runoff in 2015 was “a breather, a respite,” Deputy Interior Secretary Mike Connor said, “There is an opportunity that exists right now with that reprieve. From the administration’s standpoint, our goal is that we absolutely need a drought contingency plan. We need to add to the tools that we have right now; given, notwithstanding that progress, those projections that exist long-term in this Basin and even short-term.”

Drought-related shortages in the Lower Basin are the immediate concern but the entire 246,000 square mile Basin faces a long-term shortfall. The 2012 Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study (Basin Study) concluded that, absent any additional action, the gap between the demand for water could, under some projections, exceed supply by 3.2 million acre-feet in 2060, depending on growth, continued water use and climate change. The Basin Study was developed collaboratively by the federal government and the seven states that share the Colorado River – Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming.

How to close that gap in as equitable way as possible is the long-term challenge.

Response to the 16-year drought has already established principles, policies and partnerships that should help these stakeholders confront the long-term issues related to supply and demand. Water management measures that were initially implemented as drought-response activities have become common, everyday practices. The list of significant actions incorporated includes: paying customers to replace sod with water-efficient landscaping, mandating water-efficient household fixtures, lining earthen canals to reduce seepage, installing drip irrigation and other on-farm improvements, and initiating agreements to facilitate water marketing.

Major reforms also have been implemented at the institutional level:

• The 2003 California’s Quantification Settlement Agreement, which quantified the amount of water California water agencies receive annually and established rules governing water conservation and transfer agreements, including the transfer from Imperial Irrigation District to San Diego County Water Authority

• The 2007 Seven States Agreement and federal Record of Decision (ROD), in place until 2026, which includes Lower Basin shortage guidelines, guidelines to store conserved water in Lake Mead the coordinated operations of Lakes Powell and Mead under high and low reservoir conditions

• Minute 319 to the 1944 U.S.-Mexico water treaty, adopted in 2012 and in place until the end of 2017, which created a binational framework to address shortages and allows Mexico to store unused water in Lake Mead “The new institutional arrangements that have been created amongst parties – which are essentially ways to share water, to create supplies where it’s needed – are really key to the progress that’s been made, looking back over the last 10 years in particular,” Connor said at the Water Education Foundation’s September Colorado River Symposium held in Santa Fe. “Looking forward, I think those arrangements are going to be key to very specific strategies that we need to facilitate.”

Currently, while 16.5 million acre-feet of water is allocated annually for use throughout the Basin, annual rain and snow provide on average only about 15 million acre-feet, an amount that has been declining because of drought. It is the storage – 60 million acre-feet – that has allowed for the continuation of full deliveries since 2000. But with the Lower Basin – Arizona, California and Nevada – hovering just above the first tier shortage level, the focus is not just on getting customers to conserve in the districts but on conserving water to keep it in the system.

Indeed Lower Basin water left in Lake Mead through the Intentionally Created Surplus (ICS) program adopted in 2007 and the Intentionally Created Mexican Allotment (ICMA) included in the 2012 Minute 319 is credited with helping to push back the immediate shortage concern. More recently, Reclamation, CAP, Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD), Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) and Denver Water have provided funding for pilot projects designed to save additional water and keep it in the system.

“Every drop counts. And the drought we’re in, we can’t forget that. And we can’t forget it for a couple of reasons,” said Terry Fulp, regional director of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Region. “We can’t forget it because things like Miracle May can and sometimes do happen. Certainly, that’s not a drought contingency plan. But I think also we have to remember it in terms of our actions because as we go forward, we have to really think about trying to make every drop count and that includes both on how we use the water and in terms of not always using the water.”

The Basin Study did not recommend any specific actions to address the projected gap between supply and demand; but, subsequent working group discussions and studies resulted in the release of the Moving Forward report in May 2015 in which continued urban conservation and water reuse are identified as means to help close that gap. On the agricultural side, additional water conservation and marked-based transfers are projected to reduce water use but a specific amount is difficult to quantify given a variety of factors.

Through the Moving Forward initiative and its workgroups, stakeholders are committed to finding tools to help close the gap – with the goal of following the pattern of innovative solutions to date, working together at the federal, state and local levels to implement actions. Environmental, recreational, hydropower and tribal issues must all be considered as well as international partnerships between the U.S. and Mexico.

There is no dispute over how big a challenge it will be. The Colorado River is no stranger to conflict and controversy. Compromises have often come about only after the various interests have been forced to the table because of potential and/or actual regulations and litigation. Some key agreements must soon be renegotiated. And even with the best projection of water use and supply, climate change remains a wild card.

Bob Johnson, former Reclamation commissioner, is not fazed. “I think there’s an optimistic future for solving the problems on the Colorado River. I think there’s a history of doing just that,” he told participants at the September symposium, pointing to the accomplishments that have occurred over the last 20 years. “I predict 20 years from now we’ll be sitting here and there will be a long list of additional things that were accomplished. I will tell you that I don’t think it will be pretty. I don’t think there will be litigation. But I will also say that if seven states don’t do it, the secretary of Interior will and there will be leadership and there will be conclusions drawn to these issues. And everybody will be cheering at the end, but there will be hardship in between in difficult times.”

by Sue McClurg

Editor’s Note: 2016: A year of change

It seems everywhere we turn in California, a drought has gripped our major sources of water. But nothing to date has been as long as the dry period on the Colorado River, the mighty lifeblood of the Southwest that snakes through seven states and Mexico. At 15 years and counting, the Colorado drought has more than 10 years on California’s drought.

But the Colorado’s two massive reservoirs – Mead and Powell – have stored water collected over several years. The fear of a shortage being declared on the river was skirted for 2016, but that could change in 2017 as you can read in this issue of Western Water.

This coming year, we will see if El Niño will make a dent in the Southwest’s more than usual aridity. As of now, it’s still unknown. So much will depend on the amount, timing and location of the snow and rain.

But change is definitely in the air this coming year with Western Water, our flagship publication first published in 1977. Starting in 2016, it will become a quarterly instead of a bimonthly magazine. The new quarterly will be a more robust magazine with regular profiles of people and places key to water issues. And we will still publish an in-depth article of a pressing issue, the kind of coverage that is mostly missing in today’s newspapers. Don’t be shy; let us know how you like the new magazine when it comes out.

And new to our tour line-up in 2016 is a two-day San Diego trip in May with a highlight being the new ocean desalination plant in Carlsbad. At a cost of $1 billion to build, the plant just recently began operations.

Even if El Niño helps this year, will extended dry periods be the “new normal” in California as some have suggested? We will attempt to answer that question at our annual conference, the Executive Briefing, which will be held on St. Patrick’s Day on March 17.

And don’t forget about Water 101, coming up in early February 2016 in the Sacramento area. This once-a-year event is a good opportunity for anyone wanting to go beyond the headlines and gain a deeper understanding of the history, hydrology and legal system behind California water.

Click here to find more information about all of our tours and conferences.

I hope 2016 will be a year filled with good health and happiness for all of our readers, and with luck more snow in the mountains.

by Jenn Bowles