Outdated Dams: When Removal Becomes an Option

Summer 2016

Mired in drought, expectations are high that new storage funded by Prop. 1 will be constructed to help California weather the adverse conditions and keep water flowing to homes and farms.

At the same time, there are some dams in the state eyed for removal because they are obsolete – choked by accumulated sediment, seismically vulnerable and out of compliance with federal regulations that require environmental balance.

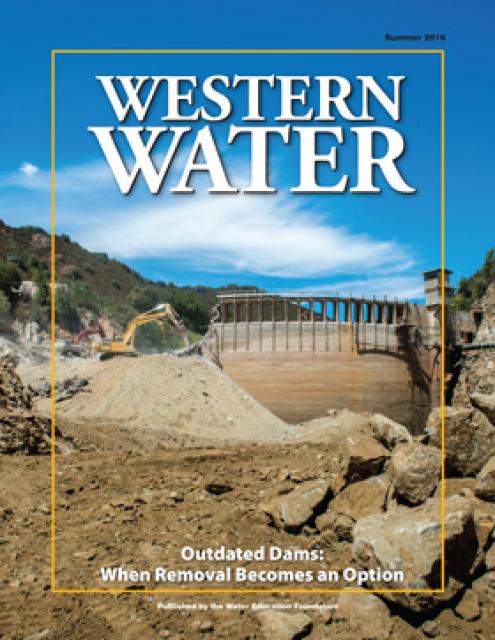

Efforts are gearing up on the Klamath River between Oregon and California to remove four hydroelectric dams by 2020, restoring access to more than 400 miles of historic salmon and steelhead trout habitat. The 106-foot San Clemente Dam in Monterey County met the wrecking ball in 2015, opening up miles of new spawning habitat for salmon and steelhead. And, in Southern California, two dams are targeted for removal because they no longer serve a useful purpose and block access to fish habitat.

But in a state that depends on storage during wet winters to use that water during dry summers, dam removal is especially site-specific.

The rim dams, the large dams at the base of most major river systems in California, serve a vital function – storing water that is used to irrigate farms and drinking water to millions of people as well as providing critical flood protection. No one calls for their removal.

Read the excerpt below from the Summer 2016 issue written by Gary Pitzer along with the editor’s note from Jennifer Bowles. Click here to subscribe to Western Water, a quarterly magazine, or to purchase just this issue.

Introduction

Mired in drought, expectations are high that new storage funded by Prop. 1 will be constructed to help California weather the adverse conditions and keep water flowing to homes and farms.

At the same time, there are some dams in the state eyed for removal because they are obsolete – choked by accumulated sediment, seismically vulnerable and out of compliance with federal regulations that require environmental balance.

Efforts are gearing up on the Klamath River between Oregon and California to remove four hydroelectric dams by 2020, restoring access to more than 400 miles of historic salmon and steelhead trout habitat. The 106-foot San Clemente Dam in Monterey County met the wrecking ball in 2015, opening up miles of new spawning habitat for salmon and steelhead. And, in Southern California, two dams are targeted for removal because they no longer serve a useful purpose and block access to fish habitat.

But in a state that depends on storage during wet winters to use that water during dry summers, dam removal is especially site-specific.

The rim dams, the large dams at the base of most major river systems in California, serve a vital function – storing water that is used to irrigate farms and drinking water to millions of people as well as providing critical flood protection. No one calls for their removal.

“Dam removal because the dam is unsafe or of no value is actually very rare for the bigger dams in California,” said David Gutierrez, chief of the Department of Water Resources’ (DWR) Division of Safety of Dams. “Dams in California are providing a variety of benefits and dam owners have worked hard to continue maintaining the dams in a safe manner.”

Dam removal is expensive, usually exceeding $100 million, not including the cost of initial studies. But for some dam owners the cost of removal is less expensive than effecting the necessary modifications such as fish ladders or seismic safety retrofits.

“I think ultimately what you are talking about is comparing the costs of alternatives,” said Andrew Fahlund, deputy director with the Water Foundation. “You are comparing the cost of repair and rehabilitation to the cost of removal, and, of course, the cost of removal includes the loss of whatever benefits the dam provided. It also includes the benefits of whatever the removal results in.”

Dams are targeted for removal primarily as a safety issue, but in other cases they simply aren’t doing what they were designed to do.

“I am the first to say there are dams that make sense and that serve important societal and economic needs,” said Jock Conyngham, research ecologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) Environmental Laboratory in Missoula, MT. “However damaging their environmental signal, in the larger calculus they justify their existence and play important roles.”

That said, “a lot of dams really do not fulfill their intended mission or don’t justify their impacts for one reason or another,” Conyngham added.

Fahlund said the process begins with evaluating whether a dam is still efficiently doing the job its builders intended.

“The way I like to think about it is that dams are really just simply tools and tools wear out and become obsolete,” he said. “We have to stop looking at dams as sort of religious in nature and more utilitarian.”

For other dams, however, their value must be weighed carefully against the expense of removal.

“It’s a lot easier to make the argument to take down a dam that no longer serves any purpose and that is even perhaps hazardous than a dam that’s still providing water, power or flood control,” said Sam Schuchat, executive director of the California Coastal Conservancy.

The Conservancy helped pay for the removal of San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River about 15 miles southeast of Monterey and wants to do the same for the similarly ailing Matilija Dam on Matilija Creek in Ventura County. Obsolete and hazardous, San Clemente was taken down by its owner, California-American Water, because of the expense required to rehabilitate it to proper standards.

A well-publicized dam removal effort centers on O’Shaughnessy Dam, which holds Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and provides water to more than 2 million people in the Bay Area. The environmental group Restore Hetch Hetchy wants to remove the dam to restore Hetch Hetchy Valley in a corner of Yosemite National Park, but the city of San Francisco, which owns the dam, steadfastly opposes the idea, citing O’Shaughnessy’s role in providing water supply, power generation and cold water flows for the Tuolumne River.

San Francisco voters in 2012 rejected a ballot measure that was to order a study of the future of Hetch Hetchy. In April, a Tuolumne County Superior Court judge ruled that the Hetch Hetchy system is not an unreasonable diversion of water.

There are many small dams outside state or federal jurisdiction “that affect a relatively small tributary or small watershed but that are doing nothing for anybody,” said Peter Brewitt, professor of environmental studies at Wofford College in Spartanburg, SC. These “feral dams” cause problems “without any economic functionality at all.”

Brewitt, whose doctoral thesis at the University of California, Santa Cruz, was called “Same River Twice: Restoration Politics, Water Policy, and Dam Removal,” [a book is forthcoming] said that with the benefit of hindsight, “we’d have built a lot of the same dams but we would have built fewer of them and operate them differently.”

Recognition that dams could be feasibly removed is a fairly recent phenomenon in California and the rest of the country.

“Dam removal really was not a thing that happened until the 1990s and really the beginning of the 21st century,” Brewitt said. “There were a few in the 1980s, a few more in the 1990s and now for the last 15 or 20 years, they’ve been taking out 50, 60, 70 [nationwide] a year.”

Dam removal is much more than simply removing the physical structure and letting a river or creek return to its former state. It’s a major undertaking involving a multitude of groups trying to ensure the process does no harm and ultimately achieves the desired results. In addition to trapping water, dams trap sediment, a lot of it, and when the time comes to consider removal, managing the sediment is perhaps the top consideration.

Sediment management “is by far the most expensive and complicated part of the entire enterprise,” Fahlund said. “If not the contamination issue then the sheer volume of it can be a problem. Dredging it or letting it go depends on the river’s downstream environment. It may be that letting nature take its course is most suitable. We have learned that if you give rivers the opportunity to move those sediment loads they tend to do it a lot faster and lot more effectively than people had realized.”

Sediment can inhibit the ability of dams to do the job for which they were built. The Central Valley Project’s (CVP) Folsom Lake on the American River, for example, is estimated to have lost 45,000 acre-feet of storage from the accumulation of more than 72 million cubic yards of sediment behind the dam. Not all reservoirs are susceptible to sedimentation, but the problem is illustrative of an ongoing discussion about dredging and the related costs.

The 265-foot high Englebright Dam on the Yuba River, which was built as a retention facility, has been discussed for possible removal. However, it holds more than 28 million cubic yards of mining debris, some of it contaminated with mercury. Removing it presents significant public health and safety risks and could cost as much as $3 billion, said Curt Aikens, general manager of Yuba County Water Agency (YCWA).

“Englebright provides a really important public safety function,” Aikens said. “One of the concerns is if you were to remove the dam, what would happen with the sediment? Would it reduce the flood channel capacity of the Yuba or Feather, presenting new flood risk to nearby communities?”

Marvels of engineering ingenuity, dams harness the power of rivers and creeks for several beneficial purposes – water supply, flood control, hydropower production – along the way achieving a sense of permanency. The environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s stirred discussion of dam removal. Not much happened initially but the stage was set in which the idea of removing a dam moved beyond fringe environmentalism into the realm of the possible.

“It’s quite reasonable for us to question that if a dam is no longer fulfilling its intended purpose whether it should remain standing,” former Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Dan Beard wrote in his 2015 book, Deadbeat Dams. “Our political institutions approve dam projects for a specific set of reasons at a particular point in time. After 40 or 50 years, things change. Today, everyone would agree that we have a different economy, a different set of environmental values, and different social values than we did fifty years ago. If that’s the case, why should we blindly accept and live with decisions made fifty or a hundred years ago if those are inconsistent with today’s values or economy?”

A significant milestone in dam removal occurred in 2014 with the removal of two dams on the Elwha River in the state of Washington – the largest dam removal project ever. After more than 100 years, the Elwha River’s path to the sea was freed, rejuvenating long-dormant salmon and steelhead habitat and giving scientists a front row seat for what restoration looks like.

“The Elwha is almost a pure example of what can happen to a river when you take out dams because there are no other developments in the wilderness upstream of the dams,” Brewitt said. “How [it] responds will be a good opportunity to see what dam removal can do for a riparian ecosystem.”

– by Gary Pitzer

Editor’s Note: The Story Behind the Headline

The idea for this issue came from Sue McClurg, the Foundation’s deputy executive director, whose father was an engineer at the Department of Water Resources. She was interested in finding out how the decisions were made to remove outdated dams and what steps were needed to deconstruct them. It’s usually a complicated and costly undertaking as you’ll read in this issue of Western Water. Sometimes, the river itself has to be re-routed.

Dam removal is a sensitive subject in California right now as its cities and farms continue to struggle through a fifth year of drought. The supply stockpiled behind dams and the possibility of adding new storage are seen as vital resources to provide the surface water needed to help balance over-drafted groundwater basins as required under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). But this issue is not looking at those classic California dams – Shasta, Oroville, etc. – that hold back water for drinking or irrigation purposes. This article explores the smaller dams across California that have become obsolete because of sediment build up, seismic vulnerability or outdated federal compliance that would require costly repairs. Such is the case with four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River which straddles Oregon and California.

At the Foundation, we believe it’s our mission to help inform our readers about what is going on in the world of water in California and the West, and this issue is one that keeps popping up. We use Western Water to explore an issue deeply, to understand the discussions and debate that center around it, information that’s not usually included in a newspaper article. And we hope this magazine issue is successful at examining this important topic.

Another hot topic these days is groundwater, and so we’ve added a new tour to our fall line-up. You may ask how can one see groundwater on a tour? Well, we go to sites – dairies, ranches and vineyards for instance – where groundwater is being used, and discuss management, over-use, subsidence and how agencies are implementing SGMA. We did a groundwater tour last fall, and it was wildly popular. We’re updating this one with new site visits so check it out.

Join us on that tour or another one in our fall line-up!