Rewriting History: California’s Epic Drought

September/October 2015

Drought doesn’t instantly ravage

the way flooding does. It advances at a steady, determined pace,

building and spreading during several years. Fields wither,

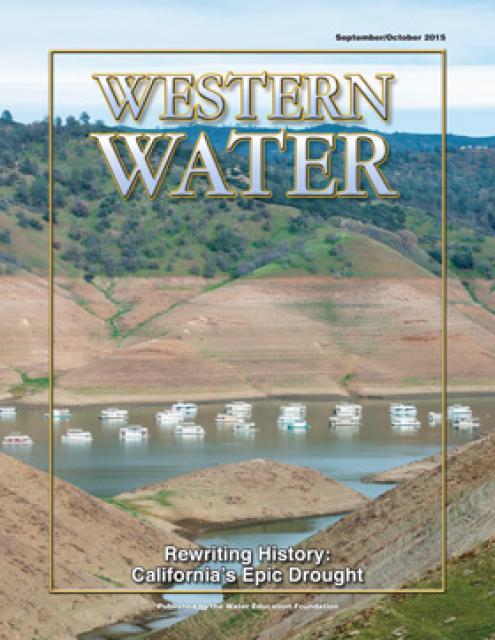

reservoirs drop to dangerously low levels and the memory of what

constitutes a normal water supply becomes more distant.

Drought doesn’t instantly ravage

the way flooding does. It advances at a steady, determined pace,

building and spreading during several years. Fields wither,

reservoirs drop to dangerously low levels and the memory of what

constitutes a normal water supply becomes more distant.

Read the excerpt below from the Sept./Oct. 2015 issue along with the editor’s note. Click here to subscribe to Western Water and get full access.

Introduction

Drought doesn’t instantly ravage the way flooding does. It advances at a steady, determined pace, building and spreading during several years. Fields wither, reservoirs drop to dangerously low levels and the memory of what constitutes a normal water supply becomes more distant.

Swings between wet and dry periods are the hallmark of California’s semi-arid, Mediterranean climate. A glance at the state’s history reveals incidents of overwhelming floods and years of crippling drought; droughts that left the landscape dotted with withered trees and the bleached bones of dead cattle.

The cumulative years of deficit – combined with record heat – have taken their toll. The 2014 water year tied the 1977 water year with a snowpack of 25 percent of normal. Water year 2015 was even worse. On April 1, 2015, Gov. Jerry Brown stood in a bare field in the Sierra Nevada that would normally be covered in several feet of snow to show the world what California was facing.

The drought is easy to see if one considers reservoir storage levels throughout the state: Lake Shasta at 33 percent of capacity; Oroville, 30 percent; Folsom Lake, 17 percent and Millerton Lake, behind Friant Dam, 36 percent. Some southern San Joaquin Valley reservoirs are in even worse shape: Pine Flat, 12 percent; Exchequer, 8 percent.

Experts believe the fourth year of drought that began in 2015 is charting new territory.

“Although droughts are a regular feature of the state’s climate, the current drought is unique in modern history,” the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) noted in its August report, “What If California’s Drought Continues?” “Taken together, the past four years have been the driest since record keeping began in the late 1800s.”

During an Aug. 21 panel discussion of the report in Sacramento, Ellen Hanak, director of PPIC’s Water Policy Center, said the drought “is what we can expect as the climate warms,” and that it is “a dry run for the ‘hot-dry’ future.”

Drought impacts have varied across the state. Urban areas are coping due to diversified water portfolios and conservation with some areas doing better than others. “If this drought has one bright spot, it is that California’s cities and suburbs – home to 95 percent of California’s population and an even higher share of economic activity – have become considerably more resilient since the 1987- 92 drought, despite the addition of more than eight million residents since that time,” PPIC’s report said.

Agricultural supplies have been hard hit in some areas; some farmers have received zero allocations from the Central Valley Project, for example. But farmers are also coping, though the monetary losses caused by lost production are not insignificant.

According to a report by the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California, Davis, “Economic Analysis of the 2015 Drought For California Agriculture,” the state’s agricultural economy directly will lose about $1.84 billion and 10,100 jobs in 2015 because of the drought, with the Central Valley “hardest hit.”

Continuation of the drought means agricultural production and employment “will continue to erode,” said water economist Josué Medellín-Azuara, co-author of the report.

State and federal estimates suggest that a ballpark value for irrigated land fallowed in 2015 specifically due to drought was about half a million acres.

“What has saved agriculture at the macro level is commodity prices are good and impacts in local areas are masked by statewide conditions,” said Jeanine Jones, interstate resources manager for the Department of Water Resources (DWR), during a Sept.1-2 drought tour of the southern San Joaquin Valley. The tour was organized and conducted by the Water Education Foundation with support from DWR. “The impacts are masked by high crop prices.”

With the loss of surface water supplies, growers in the San Joaquin Valley have expanded groundwater pumping, straining an already over tapped resource. It isn’t as easy to see as in a surface water reservoir, but the pumping has increased overdraft. And in some places, taking so much water causes the ground to sink, by several feet in some places.

DWR in August released a report by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration showing that land in the San Joaquin Valley is sinking faster than ever before, nearly two inches per month in some locations.

The report said land near Corcoranin the Tulare basin sank 13 inches in eight months. The phenomenon threatens the integrity of the California Aqueduct, where nearby subsidence sank the land eight inches in four months of 2014.

Overpumping aquifers has been likened to the clear-cutting of forests in its severity and permanence.

“There are areas in the San Joaquin Valley by the East Side Bypass that have subsided several feet in less than a decade,” Jones said. “It is the canary in the coal mine for groundwater management.”

Farmers have resorted to sinking deeper wells with more powerful pumps, an activity that inevitably draws water from adjacent properties.

While fields are irrigated, farmworkers living near them struggle to get a reliable supply of potable water. Laurel Firestone, co-executive director of the Community Water Center, told the PPIC audience that “very limited data” exists regarding the status of drinking water wells that could go dry in farmworker communities.

“It’s drastically underreported,” she said. “We need to know where the vulnerable wells are. Right now, it’s completely inadequate.”

Thus far, state and local agencies have poured millions of dollars into drilling new wells and providing temporary water for hard-hit communities in the southern San Joaquin Valley where having regular access to water is a struggle. Drought “exacerbates the pre-existing problems” of small water systems, Jones said.

A glimpse at the small communities dotting the east side of the San Joaquin Valley during the Sept. 1-2 drought tour revealed people relying on portable water tanks or small individual wells. Some houses actually have enough water to maintain verdant lawns while other homes are fronted by patches of dirt. In 2011, United Nations officials visited the Tulare County community of Seville, population about 500, and found the drinking water conditions similar to Third World countries.

Local officials have scrambled to bring in bottled water, water tanks and to drill new wells to replace the ones that have gone dry. According to The Fresno Bee, about 700 families In the Tulare County community of East Porterville have no running water.

Some people have gone as long as a year or more without water in their home, said Omar Carrillo, senior policy analyst with the Community Water Center, based in Visalia. “This means no water for drinking, showering, cleaning clothes and keeping themselves cool during this blistering summer,” he said. The lack of water means residents have to spend as much as 10 percent of their income on water and lug it back home.

“Think about having to go fill up a 55 gallon tank and then taking water from that for a year,” said Mario Santoyo, director of the California Latino Water Coalition, during the tour. “We are back in pre-project days.”

Because of their small, low-income ratepayer base, it is difficult for systems with a handful of connections to upgrade to a steadier, more reliable water system. Long-term, it’s believed the answer lies in expanding the population of those who would benefit from improved services by consolidating systems to increase the ratepayer base.

Since the drought emergency was declared in January 2014, millions of dollars in state and federal aid have been spent on emergency drought relief and water system investments for hard-hit communities.

“These efforts have helped limit the economic impacts of the drought so far,” PPIC’s report said. “But the experience is also revealing major gaps in California’s preparedness to cope with the social and environmental impacts of extended, warm droughts. Too many decisions are being made on an emergency basis with the hope that the next winter will bring much-needed rain.”

The drought has caused a dramatic reduction in flows for the environment and has contributed to an unprecedented number of wildfires. The lack of water cuts necessary flows for fish and pushes the water temperature to the extremes of what they can tolerate. Continued drought threatens the vitality of native fish, making the job of preservation that much harder for wildlife managers.

“Unfortunately, we are in a place where success means avoiding extinction,” Kevin Hunting, chief deputy director with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW), told the PPIC audience. The drought necessitated the department’s trucking of 3 million salmon smolts from upstream hatcheries to points closer to ocean entry to ensure their survival, he said.

The drought’s severity is evident in the charred remains from several severe wildfires, including the Butte Fire, which burned more than 70,000 acres in Amador and Calaveras counties. Experts studying the phenomenon believe that the increase of higher-elevation forest fires is “yet another harbinger” of climate change.

“With California currently in the midst of a four-year drought, low snowpack in the mountains and related forest stress are further increasing the chances of large, destructive fires that move high into the Sierra,” said Mark Schwartz, a professor of environmental science and policy and director of the John Muir Institute of the Environment at UC Davis.

The drought exposes the raw emotions surrounding water allocation, reviving the complaint that “wasted” water sent out to the sea could be better used to irrigate fields.

“As a farmer, I can account for the amount of food I produce with the water I have: the amount of ‘crop per drop,’” Paul Wenger, president of the California Farm Bureau Federation, wrote in an April opinion piece, published in The Sacramento Bee. “But those who ‘manage’ environmental water have no such ability or requirement to account for the effectiveness of those flows. It seems the 1 gallon of water it takes to produce an almond that a person is going to eat is bad, but the thousands of gallons of water dedicated to each fish that feeds no one is OK.”

Jeff Mount, senior fellow with the PPIC Water Policy Center, told Western Water in an email that it is true that “we cannot measure return on environmental water in the same way we do urban and agricultural uses,” but that “painting the environment as the villain in drought, while simple and effective as a communication tool, misses the details.”

Writing on PPIC’s blog in April, Hanak and Mount noted that of the 4.2 million acre-feet of water that flowed through the Delta to the ocean last year; about 75 percent of it was needed to repel salinity to keep the Delta water usable for people.

“In addition, 450,000 acre-feet of water generated by three storms could have been exported, but Delta export pumps lacked the physical capacity to capture the water,” they wrote.

The drought has magnified the importance of water transfers, groundwater pumping, water rights and the renewed sense of the value of water in California. In retrospect, it may be seen as the transformative moment in the state’s history when the relationship between people and their water use forever changed for the better.

Editor’s Note: Location, Location, Location

Will El Niño be a stud or a dud this year? That was a question posed earlier this year by one of my favorite climatologists, Bill Patzert at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. Forecasts call for a 95 percent chance that El Niño will hit the Northern Hemisphere this winter, and it could be one of the strongest in recorded history.

But like real estate, the most important aspect we should be concerned about is location, location, location. Where will the rain actually fall? That’s important because the weather phenomenon is known more for bringing rain to Southern California, which we have already seen this fall. But Northern California is where much of the state’s reservoir capacity is located. So cross your fingers.

What we really need is a good ski season in the Sierra, but with snow that is heavy in water content. That really does so much more for our water systems than rain. Snow slowly melts in the spring and brings us much-needed water in the hot summers. Hard, fast rainstorms don’t always give us the chance to collect all the rain before it washes out to sea.

The impacts from this four-year drought have been severe in some cases. In early September, the Foundation held its first-ever tour focused solely on drought. The tour went deep into the hard-hit San Joaquin Valley to hear about the issues from farmers, ranchers and communities. You can read about the tour and the drought in this issue of Western Water.

With the opening of the ocean desalination plant in Carlsbad in November of this year, all eyes will be on how that facility performs. And while it will help the San Diego region by generating a new water supply, no one is expecting it to be a drought-buster.

With more than 1,000-miles of shoreline abutting California, it would seem like a natural solution to simply build more desalination plants along the coast. But, like most things, there are drawbacks: They are expensive to build and operate, take a lot of energy, can impact marine life and can only treat so much water at a time.

Metropolitan Water District of Southern California gets about 30 percent of its water from Northern California through the State Water Project. “To replace that supply (with desalination water) would require a Carlsbad plant every 4 miles between LA and San Diego,” said Jeff Kightlinger, Metropolitan’s general manager. That is a telling figure because that would be 25 plants along that stretch of coastline. Its may be difficult to convince a state in love with its beaches to go for something like that.

But the idea of ocean desalination is still alluring as a new source of water, and we are planning a tour of the Carlsbad plant in the spring. Stay tuned for more details! Or check out our website at www.watereducation.org/general-tours.