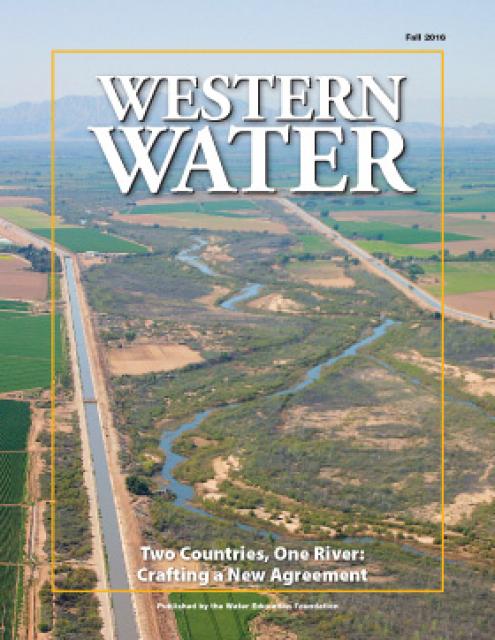

Two Countries, One River: Crafting a New Agreement

Fall 2016

As vital as the Colorado River is to the United States and Mexico, so is the ongoing process by which the two countries develop unique agreements to better manage the river and balance future competing needs.

The prospect is challenging. The river is over allocated as urban areas and farmers seek to stretch every drop of their respective supplies. Since a historic treaty between the two countries was signed in 1944, the United States and Mexico have periodically added a series of arrangements to the treaty called minutes that aim to strengthen the binational ties while addressing important water supply, water quality and environmental concerns.

The two countries consider minutes as the way to interpret or implement the treaty without adding to it. Officials say they want to complete the next treaty minute, informally known as “32X,” before the next presidential administration begins in January 2017. (Once a minute 32X is actually agreed upon, it will be assigned a number, such as 321, so it is sequential with the other minutes dating back to 1946.)

“We do have urgency,” said Edward Drusina, U.S. commissioner of the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC). “We want to accomplish something this year.”

Read the excerpt below from the Fall 2016 issue written by Gary Pitzer along with the editor’s note from Jennifer Bowles. Click here to subscribe to Western Water, a quarterly magazine, or to purchase just this issue.

Introduction

As vital as the Colorado River is to the United States and Mexico, so is the ongoing process by which the two countries develop unique agreements to better manage the river and balance future competing needs.

The prospect is challenging. The river is over allocated as urban areas and farmers seek to stretch every drop of their respective supplies. Since a historic treaty between the two countries was signed in 1944, the United States and Mexico have periodically added a series of arrangements to the treaty called minutes that aim to strengthen the binational ties while addressing important water supply, water quality and environmental concerns.

The two countries consider minutes as the way to interpret or implement the treaty without adding to it. Officials say they want to complete the next treaty minute, informally known as “32X,” before the next presidential administration begins in January 2017. (Once a minute 32X is actually agreed upon, it will be assigned a number, such as 321, so it is sequential with the other minutes dating back to 1946.)

“We do have urgency,” said Edward Drusina, U.S. commissioner of the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC). “We want to accomplish something this year.”

The IBWC – an international body composed of the United States Section and the Mexican Section, each headed by an Engineer-Commissioner appointed by his/her respective president – interprets the treaty and executes the minutes. In 2012, the IBWC signed Minute 319, a five-year agreement that, among other things, created a program by which Mexican water resulting from conservation and new water sources could be held in U.S. reservoirs for future delivery. It also included a historic 2014 pulse flow where for the first time ever, the United States and Mexico released water from Morelos Dam in Mexico into the dry Colorado River channel for the purpose of rejuvenating habitat in the Colorado River Delta. Ultimately, this flow reached the sea, marking the first time in decades that connection was made.

Although that agreement does not expire until Dec. 31, 2017, stakeholders believe it is the existing relationship among current leaders/negotiators that is the foundation for approval of a new minute.

Described as both an extension and an improvement of Minute 319, Minute 32X will likely feature an expanded pilot water conservation program element in which U.S. investments in Mexican infrastructure would benefit Mexico and result in some direct yield to U.S. water users and an overall boost to the Colorado River system. Under Minute 319, about $10 million in improvements is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2017, though that process is lagging.

Work on Minute 32X is occurring among a landscape that is fraught with complexity but also offers opportunities for greater water conservation and environmental stewardship.

“It’s another very important step in our collaborative approach with our partners in Mexico,” said Terry Fulp, director of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Region. “The countries have been on a path the better part of 10 years of finding working arrangements and solutions that benefit both.”

The next treaty minute is linked to a series of minutes that began in 2010 primarily in response to Mexico’s request for emergency storage in U.S. reservoirs because of earthquake-damaged infrastructure in the Mexicali Valley. Minute 318 allowed Mexico to defer delivery of a portion of its annual Colorado River water allotment of 1.5 million acre-feet through 2013 while the irrigation system was repaired. That water, in turn, has helped keep Lake Mead’s level above the trigger point for a shortage declaration.

Work on Minute 32X is emerging as news of a drying river system dominates the headlines. While there will not be mandatory shortages to the Lower Basin states (Arizona, California and Nevada) nor reductions to Mexico in 2017, current projections show essentially a 50 percent chance of having the first round of mandatory water cutbacks in 2018.

“The bottom line is we are riding this bubble, riding the edge and I think the [2007] Interim Guidelines that allowed the water banking concept in Lake Mead are working pretty well given the hydrology we have,” Fulp said, referring to the 2007 federal Record of Decision for Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Those guidelines established reservoir levels in Lake Mead that could trigger shortage declarations in the Lower Basin and a methodology for determining annual releases from Powell and Mead throughout the full range of reservoir operations until 2026.

Among the Lower Basin states, California is the largest user of Colorado River water – Southern California counts on the river for more than 50 percent of its supply, according to the Colorado River Water Users Association. But under the existing shortage guidelines, Arizona and Nevada would take the shortages, not California. The state is, however, working with Arizona and Nevada on a voluntary Drought Contingency Proposal.

The epic dryness has thrown an unknown variable into how the negotiations proceed. There is hope for additional environmental flows for the Delta as well as discussions about Mexico’s participation in a U.S.-led drought contingency plan.

“The issues are more straightforward to address when we are not in a shortage situation than trying to negotiate a new agreement at the same time that the reservoirs are rapidly declining,” said Chuck Cullom, Colorado River programs manager for the Central Arizona Project.

Experts say results of the next treaty minutes are critical. “The storage of Mexican water in Lake Mead or anywhere upstream is going to continue,” said Gabriel Eckstein, professor of law at Texas A&M University. “There’s going to be that creative mechanism for managing water resources in a way that maximizes efficiency but in a much longer term time frame.”

Eckstein co-authored an article in 2014 called “Minute 319: A Cooperative Approach to Mexico-U.S. Hydro-relations on the Colorado River.”

Minute 32X “will look similar to Minute 319 in the sense that we know what the key issues still are that we want to address,” such as salinity, Fulp said. Furthermore, it will likely strengthen the surplus/shortage sharing framework.

“The key fundamental part of Minute 319 was the agreement of how to handle both high- and low-flow conditions,” he said. “We came up with a very fair approach in 319 where – when we have high reservoir conditions we share that benefit bi-nationally – both countries get surplus water. The flip side is when you are in low reservoir conditions we both share in terms of reductions. That was a major breakthrough in terms of our conceptual agreement as well as our actual operational agreement in 319. It’s critical we continue that equitable, fair approach.”

The 2014 pulse flow into the Colorado River Limitrophe (the 24-mile stretch that forms the U.S.-Mexico border) and Delta sent water into areas being restored by conservation groups and set the stage for future management of what was once more than 2 million acres of riparian habitat and wetlands vital to birds and wildlife. Although the amount of water talked about is less than 1 percent of the river’s average annual flow, its effect on the landscape has been exceptional.

“We view what has occurred under Minute 319 as a tremendous success,” said Jennifer Pitt, Colorado River Project director with the National Audubon Society. Environmental groups, she said, are looking forward to expanding that success with Minute 32X.

“Now that we have had the opportunity to demonstrate that restoration is possible we can take it to scale; to make a real difference at the landscape level and to ensure that there is water delivery that impacts nearly the entire river corridor from Morelos Dam down to the upper Gulf of California,” Pitt said.

From the water supply perspective, the likelihood of a shortage declaration in 2018 means maintaining Lake Mead’s water level is paramount.

“The concept that I think is hard for folks to get is that as you go down in the lake, a foot of elevation is less water because of the sloping sides of the reservoir,” Fulp said. “The lower you get the faster you can fall in terms of lake elevation. If you let the reservoir get down to where it’s only got 5 to 6 million acre-feet of water in it, then you are really at risk and if you get a couple of bad years, you just can’t make the deliveries.”

Water providers in the U.S. have employed multiple strategies to deal with the shrinking Colorado River supply, investing money in conservation projects and agreeing to shared cuts if necessary. Cullom said that because of Minute 319, which included a shortage sharing provision, “Mexico is aware of those programs and has the opportunity potentially in the next minute to participate or at least coordinate their actions with those in the U.S. so that we have conservation programs to make the system more resilient.”

As reported in the summer 2016 River Report, California, Nevada and Arizona are working on a Drought Contingency Proposal to enroll them in what they agree is a shortage- sharing platform to avoid the undesirable aspects of Lake Mead falling to 1,025 feet above sea level – the lowest shortage trigger level contemplated in the 2007 Guidelines. If the reservoir falls below that level, there is uncertainty how the secretary of the Interior, who serves as watermaster for the Lower Basin, would administer additional shortages. The conditions of the proposal would be supplemental to the 2007 Guidelines and would not reopen or modify the terms of that agreement.

Mexico’s participation in taking voluntary reductions would be predicated on the relationship established through the previous treaty minutes.

“I think that one of the successes of Minute 319 has been the consistent, committed and transparent dialogue about the status of the Colorado River and the drivers that influence the water supply available to the U.S. and Mexico,” Cullom said. “We’ve had those discussions almost continuously since 2012 and in that way officials in Mexico and the U.S. have a deeper understanding of what the risks in the system are and the tools on both sides of the border to address those risks.”

The dire situation on the Colorado River influences the binational talks in a way not seen in 2012 when Minute 319 was negotiated. “I have always thought that these issues related to drought management were really the big issues, overarching the conservation issues in terms of the pure politics of it because guarding your water rights is the number one thing,” said Stephen Mumme, professor of political science at Colorado State University. “The whole question of how you manage for drought was left hanging in the 1944 water treaty and afterward.”

Meanwhile, Minute 319’s pledge to invest U.S. dollars into Mexico for infrastructure improvements has yet to be fully realized but there is an expectation the possibility remains viable.

Pete Silva, a consultant to the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, said Mexico would like an agreement for U.S. investment in its water infrastructure because its federal government is struggling financially. Context is important, he said, as Mexico is “very sensitive to the political side of not saying they are selling their water,” preferring the term exchange. Furthermore, they are aware of the low reservoir conditions and know it would be “politically untenable” for them not to be cut back as part of a possible drought contingency plan, he said.

Mexico’s cautious approach to its water supply is “analogous” to the view in the U.S., where water rights “are an extremely important asset,” Fulp said, adding that the idea of exchange is not unlike what is occurring through the Quantification Settlement Agreement between the Imperial Irrigation District and San Diego County Water Authority.

“The wild card will be this drought contingency because we want to put a longer term agreement in with Mexico – through 2026 is what we are contemplating – yet we are all recognizing that we can see this continual drought and even worse drought and have to do more in terms of reductions,” Fulp said. “That’s a difficult thing because without it on the U.S. side it’s very difficult for Mexico to agree to something that they don’t know what they’re agreeing to.”

Preserving Lake Mead’s water level “is a checkbook balance approach,” Fulp said, noting that “if we continue to see longer term times where we are not seeing high flows, we need to do more at this reservoir.”

The drought conditions mean that water for Delta restoration will have to be strategically applied. Between March 23, 2014, and May 18, 2014, a total of 105,392 acre-feet of water was released as a pulse flow from Morelos Dam (with a supporting base flow) at the international border, moving sediment, helping to germinate native vegetation, replenishing the aquifer and lifting the spirits of people living nearby who were used to a dry river bed. It is likely the precursor of a more comprehensive release to come.

“We proved that our decisions creating a pilot of this showed that it was on our radar and we hit the target fairly well on all these different areas,” said IBWC Commissioner Drusina. “We teed up the next minute so we can go into that discussion with some stuff under our belt that we know is working.”

Although the Foundation was unable to reach Commissioner Roberto Salmon to discuss how the IBWC’s Mexican Section views the ongoing negotiations over Minute 32X, a year ago, Luis Antonio Rascón, principal engineer for the Mexican section said their goal was to reach a cooperative agreement to meet the growing demands for water in the Basin.

Editor’s Note – Rivers Know No Borders

I’ll never forget my trip a few years ago to Minerve, a quaint village that sits above a gorge in vineyard-studded southern France. There, you can see remnants of a 1210 battle fought during the Abigensian Crusade, a 20-year military campaign waged by Pope Innocent III to rid the Languedoc region of Catharism, a religion viewed by Catholics as heretic.

Catapults still sit on the other side of the river and the

castle’s ramparts that were used to attack Minerve, where a group

of Cathars had sought refuge. After the catapults destroyed the

town’s only well, the Viscount of Minerve negotiated a surrender

to save the lives of the villagers. But those Cathars who refused

to convert to Catholicism were burned to death at the stake, 140

in all.

The account of this conflict underscores the vital role that water can play in international battles and politics.

That role became more apparent in modern-day times when Pakistan recently threatened war with India if it violated a decades-old treaty regulating river flows between the two nations, saying any violation would be “an act of war.”

The history of international water treaties dates as far back as 2500 BC, when a dispute over the Tigris River led to an agreement forged by the Sumerian city-states of Lagash and Umma, according to the Atlas of International Freshwater Agreements.

According to the Atlas, there are 263 rivers that cross international borders so the potential for complications between countries seems high.

Thus, I was struck by Stephen Mumme’s comments in this issue of Western Water that the minutes to the 1944 treaty between the U.S. and Mexico on the Colorado River are unique and exclusive to the two countries. In fact, scholars believe there is nothing like it anywhere else.

We should applaud the U.S. and Mexico for negotiating agreements that allowed Mexico to store water in Lake Mead after a powerful earthquake in 2010 damaged Mexican infrastructure and for the historic pulse flow in 2014 that breathed some life back into the river’s delta. This issue’s featured article also explores how the U.S. benefited, along with the hopes for the next minute now being negotiated.

At the Foundation, we are gearing up for next year’s events and tours, including a three-day tour that weaves along the lower Colorado River tour April 5-7. Check out the details.

Hope to see you at an event or tour in 2017!