California to Uncloak Water Rights As It Moves Records Online

WESTERN WATER SPOTLIGHT: State Also Aims to Make Water Use Data Readily Available to Public

For a state that prides itself on

technological innovation, California is surprisingly antiquated

when it comes to accessing fundamental facts about its most

critical natural resource – water.

For a state that prides itself on

technological innovation, California is surprisingly antiquated

when it comes to accessing fundamental facts about its most

critical natural resource – water.

Most anywhere else in the West, basic water rights information such as who is using how much water, for what purpose, when, and where can be pulled up on a laptop or smartphone.

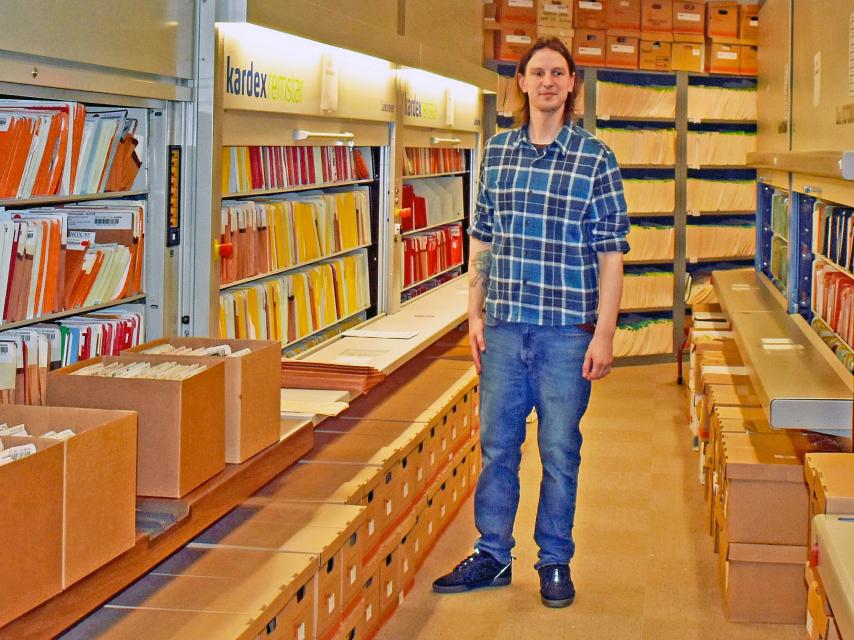

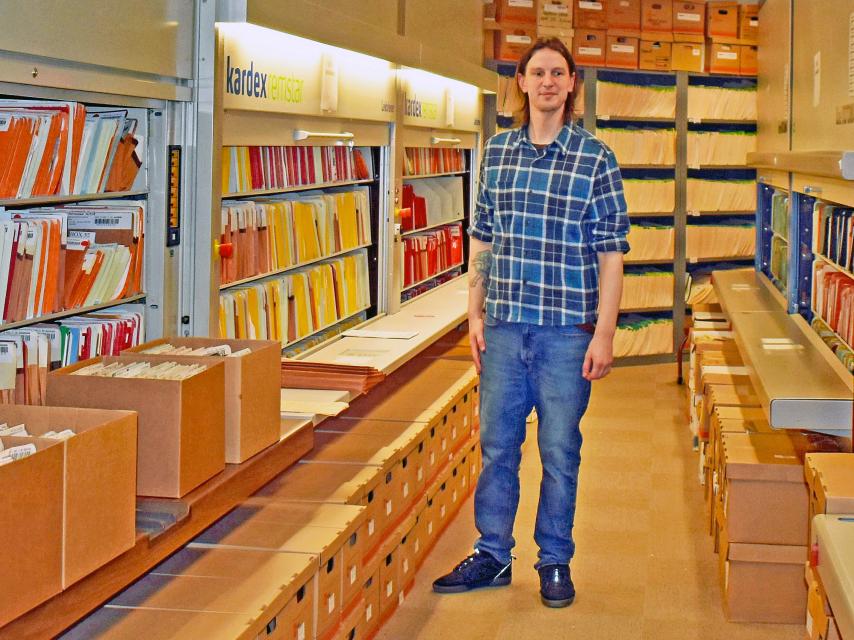

In California, just figuring out who holds a water right requires a trip to a downtown Sacramento storage room crammed with millions of paper and microfilmed records dating to the mid-1800s. Even the state’s water rights enforcers struggle to determine who is using what.

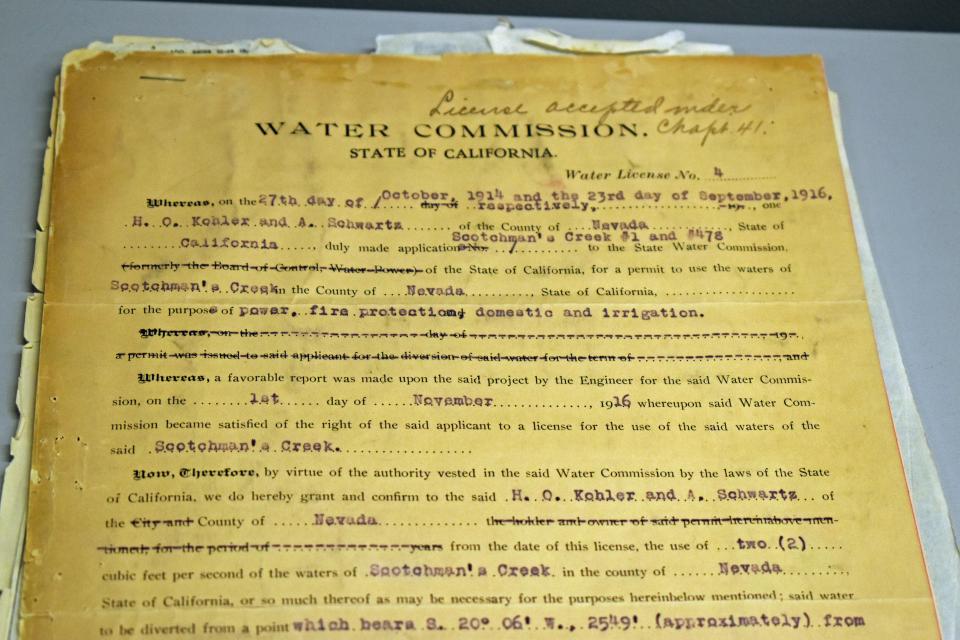

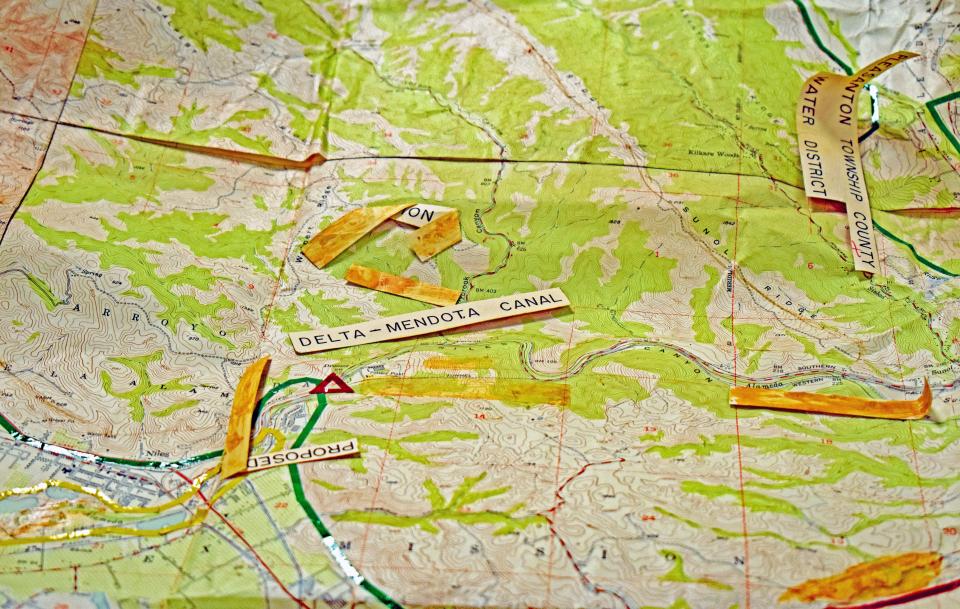

Information that can help decide who takes water cuts first during a drought or resolve water rights disputes must be unearthed by a librarian from the room’s maze of industrial filing cabinets and cardboard record boxes. The files can contain a hodgepodge of hand-written records on tattered paper, sepia photos, floppy disks and sprawling maps that require multiple staff to unfurl.

“We shouldn’t have to help people find records or make them travel to Sacramento,” said Jennifer Hernandez, a State Water Resources Control Board manager on the project. “The public deserves to see these.”

Come next year, however, the board expects to have all records electronically accessible to the public. Officials recently started scanning records tied to an estimated 45,000 water rights into an online database. They’re also designing a system that will give real-time data on how much water is being diverted from rivers and streams across the state.

The overhaul comes amid a broader

push in the Legislature to modernize a water rights system rooted

in the early days of statehood when miners, farmers and

burgeoning cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles needed to

transport water from its source to flush out gold, irrigate crops

and supply homes.

The overhaul comes amid a broader

push in the Legislature to modernize a water rights system rooted

in the early days of statehood when miners, farmers and

burgeoning cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles needed to

transport water from its source to flush out gold, irrigate crops

and supply homes.

Critics say the modernization is long overdue. A 2021 University of California, Berkeley study of the state’s water rights information system found it ill-equipped to protect people and the environment in a warming climate with increasingly severe droughts.

“Water rights data are a particularly important ingredient for understanding our water system, but they are currently difficult or impossible to access for modern decision-making,” a team of researchers wrote. “No investment in governance infrastructure could be more foundational to supporting the ability of our water system to function in the face of dramatically changing conditions.”

Proponents say the information technology upgrade will help the state and water users better manage droughts, establish robust water trading markets and ensure water for fish and the environment.

“A functional water right informational system will enable the state for the first time to bring a level of clarity to water allocation and unlock the potential for all kinds of innovation in how water resources are managed,” said Michael Kiparsky, director of UC Berkeley’s Water Wheeler Center, which led the water rights information study.

‘It’s Like a Puzzle’

The concept behind the water rights database seems basic but developing it has been challenging for the state.

“It’s like a puzzle,” said Brent Vanderburgh, a geologist who is helping manage the digitizing process at the board’s headquarters just blocks from the state Capitol. “How do you scan some of these fragile documents?”

Vanderburgh’s team has set up a “scanning arena” to process tons of records. The team inspects each file individually, removing staples and looking for duplicates. Damaged records are flagged and sent to a “triage” center to be repaired with document tape and other means. The scanned items are assigned metadata tags and geocodes that will eventually allow them to be found in simple keyword searches on the content management system.

The final product will allow users

to search for water rights and their underlying records instantly

online rather than making a trip to Sacramento or hiring a

consultant.

The final product will allow users

to search for water rights and their underlying records instantly

online rather than making a trip to Sacramento or hiring a

consultant.

The foundation for the state’s forthcoming system is based on a project between UC Berkeley and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power that produced a digital database of water rights documents from the Mono Basin. Nearly 133,000 pages were scanned over 10 days at the board’s records room.

Researchers considered the Mono Basin a perfect test case because of the variety of documents and court rulings that guide water diversions from Mono Lake tributaries. Mono Lake was the focus of a major environmental battle that ended with the California Supreme Court finding that the public trust doctrine applied to Los Angeles’ rights to divert water from the lake’s feeder streams. The landmark ruling ultimately forced the city to reduce its diversions until the lake rises 20 feet.

The Mono Lake database and accompanying report, which took more than six years to complete, demonstrated that digitizing water rights information is feasible in a state so large, Kiparsky said.

“We tried to build a case for the state to bring water rights information into the modern era … and we did,” he said.

Two-Pronged Approach

Another key objective is furnishing a water use accounting system that will give regulators and the public more insight into the scope of water being diverted from waterways. The added transparency could give regulators a better grasp of how much water is available during droughts and lead to faster, more accurate water dispute resolutions.

Since 2016, water rights holders

have been required to electronically report their water use

annually. But the information is due at the end of the water

year, meaning the figures can be more than a year old once they

reach the board. Factor in reports that have obvious data errors

or typos and regulators are often left with a murky picture of

water use in a particular watershed.

Since 2016, water rights holders

have been required to electronically report their water use

annually. But the information is due at the end of the water

year, meaning the figures can be more than a year old once they

reach the board. Factor in reports that have obvious data errors

or typos and regulators are often left with a murky picture of

water use in a particular watershed.

Erik Ekdahl, the board’s deputy director of water rights, said incomplete or inaccurate data can hamper regulatory decisions, such as whether to curtail diversions during dry years or approve water transfers between water rights holders. He said the final product will also save water users’ time and money spent on their annual reporting, as their water use data will be relayed directly to the state’s accounting database.

“We want to put the tools in place to make timely data-driven decisions, ones that aren’t based off data that comes in 18 months after the fact,” Ekdahl said.

Last fall, the board convened a group of water agencies, water rights holders, attorneys and non-governmental groups to provide feedback and test the new system as it’s being developed.

During a public meeting, multiple advisory group members cast the state’s current reporting process as being difficult to use and echoed the need for a modernized system.

“What we would like from this experience is better data and digitized material that our staff and members can access.”

~Ivy Brittain, legislative affairs director for the Northern California Water Association

“What we would like from this experience is better data and digitized material that our staff and members can access,” said Ivy Brittain, legislative affairs director for the Northern California Water Association, which represents water users in the agriculture-rich Sacramento Valley.

Brittain and the other advisory group members may get a chance to test-drive the system as early as this summer. The state has committed approximately $60 million to the project and estimates the new system could go live sometime in 2025.

The modernization of water rights records comes as state policymakers and lawmakers are taking a critical look at the water rights system.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation making it explicit that the board has the authority to investigate the validity of all water rights, including senior rights that are more than a century old and pre-date the establishment of California’s permit process. Meanwhile, a pair of bills that would have given the board broader authority to issue curtailment orders stalled in 2023 but could be brought up again this year in the Legislature.

Reaping the Benefits

Proponents contend that a modernized system will benefit the entire water spectrum, from regulators to water rights holders and even environmental groups.

In 2021, during the most recent drought, regulators ordered thousands of water rights holders from the Oregon border south into the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to stop diverting from rivers and streams. The emergency curtailments – which were based off a variety of factors including water use information from right holders – were effectively issued with stale or incomplete data.

Under the new system, Ekdahl said,

water regulators will have access to real-time diversion data

that will allow for swifter decisions.

Under the new system, Ekdahl said,

water regulators will have access to real-time diversion data

that will allow for swifter decisions.

Others argue that increasing access to basic water-use information will help water rights holders swap their supplies. These deals, which can help cities meet population growth and farmers outlast dry spells, are often bogged down by the regulatory approval process or uncertainty about how much water a seller has to offer.

A 2021 Public Policy Institute of California report suggested that a modernized system could speed up deals and help activate water markets.

“State and federal administrative reviews can be lengthy—often taking months or even years,” the research institute’s report states. “Uncertainty and delays could be reduced by improving information about water availability and how much can be traded without unduly harming the environment or other legal water users.”

Kirk Klausmeyer, director of data science at The Nature Conservancy, said the state’s database could additionally serve as a convenient directory for non-governmental organizations looking for partners on environmental projects.

“We’re particularly interested in understanding who has water rights and how we can work with them to improve outcomes for native fish and improve ecological flows in our rivers,” said Klausmeyer, who also sits on the state’s water rights project advisory group.

Digitizing public records that are crucial for establishing ownership of a water right may seem like an obvious solution. But the push for better access has met resistance from some longtime holders of California water rights.

“We’re particularly interested in understanding who has water rights and how we can work with them to improve outcomes for native fish.”

~Kirk Klausmeyer, data scientist with The Nature Conservancy

The UC Berkeley report acknowledged concerns among water rights holders that the data could make them the target of new litigation or regulations. Some doubted whether the board could be “trusted with such information,” the report said

Patty Poire, executive director of Kern Groundwater Authority and member of the state’s water rights project advisory group, said she and other water managers have reservations about the accuracy of data the board is gathering with a new technology to track and manage water use in individual crop fields. The technology, called OpenET uses satellites to measure evapotranspiration, the amount of water that evaporates or is consumed by plants.

Poire said the satellite data should be compared with measurements collected at ground level to verify accuracy.

“OpenET has been explored extensively here in the Kern subbasin,” she said during the last advisory group meeting. “Because there’s not a lot of equipment on the ground, the [OpenET] data is not as validated.”

The board’s Ekdahl said the digitization and water accounting system shouldn’t be seen as a “scary draconian regulatory action” but one that helps California navigate future challenges.

“If we’re going to make sure the existing system has longevity through climate change, population growth, land use changes, and all these different things,” he said, “then burying data in millions of pages of physical documents isn’t the way to do it.”

Reach editor Vik Jolly, News & Publications Director, at vjolly@watereducation.org

Know someone who wants to stay connected to water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water and follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram.