Can Providing Bathrooms to Homeless Protect California’s Water Quality?

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: The connection between homelessness and water is gaining attention under California human right to water law and water quality concerns

Each day, people living on the streets and camping along waterways across California face the same struggle – finding clean drinking water and a place to wash and go to the bathroom.

Each day, people living on the streets and camping along waterways across California face the same struggle – finding clean drinking water and a place to wash and go to the bathroom.

Some find friendly businesses willing to help, or public restrooms and drinking water fountains. Yet for many homeless people, accessing the water and sanitation that most people take for granted remains a daily struggle.

It is a challenge that is increasingly being recognized by water managers and communities as they work to protect water quality in rivers and waterways, and as they strive to meet the spirit of the state’s landmark 2012 human right to water law. Solving access to sanitation may help prevent the spikes in bacteria levels that have been occurring in some waterways that are sources for drinking water.

“It’s clear that people experiencing homelessness today are shortchanged in terms of access to water, sanitation and hygiene in the state right now,” Laura Feinstein, senior researcher with the Pacific Institute, an Oakland-based think tank, said at a State Water Resources Control Board workshop in April on access to sanitation for people experiencing homelessness.

That lack of access can have consequences. An outbreak of hepatitis A, a highly contagious liver disease, among homeless people and drug users in San Diego in 2017 was blamed on lack of access to public restrooms, sanitation and hygiene facilities. Over 10 months, 584 people fell ill, nearly 400 were hospitalized and 20 died.

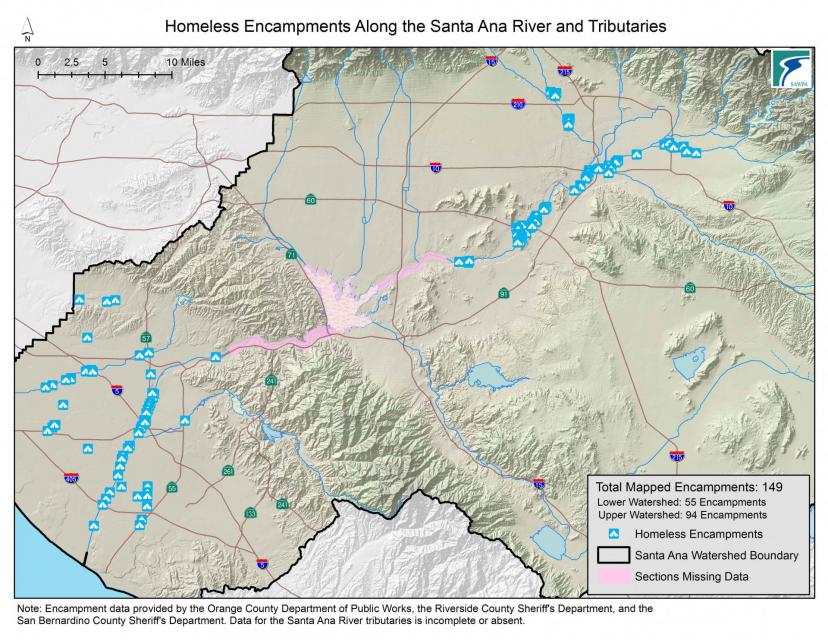

The nexus between homelessness and water is drawing increased attention. Along the American River in Sacramento and the Santa Ana River near Riverside, efforts are underway to identify the source of bacterial water contamination — whether from homeless encampments, recreational use or other sources.

The nexus between homelessness and water is drawing increased attention. Along the American River in Sacramento and the Santa Ana River near Riverside, efforts are underway to identify the source of bacterial water contamination — whether from homeless encampments, recreational use or other sources.

Meanwhile, integrated regional watershed management agencies in several regions of California are trying to engage people living with homelessness to learn more about their water-related needs. The effort is part of the state’s Disadvantaged Community Involvement Program. Some involved in the effort hope it will lead to water agencies partnering with local governments and nongovernmental organizations to develop integrated solutions for addressing the growing population of people living in homeless shelters or tents pitched beneath highway overpasses or along rivers and creeks.

While awareness is growing of the need to provide clean water and sanitation to those experiencing homelessness, finding a comprehensive solution is elusive.

Linking Sanitation and Surface Water

California had about 130,000 homeless people as of January 2018. That’s about a quarter of the nation’s entire homeless population. (By comparison, California’s share of overall population is only about 12 percent.) More recent counts in some regions of the state suggest the homeless population is continuing to grow, with increases between 2017 and 2019 ranging as high as 43 percent in some areas of the San Francisco Bay Area and Southern California.

Those kinds of increases, and the growing recognition of the magnitude of the problem, have spurred policymakers to act. Gov. Gavin Newsom included $1 billion in his state 2019-2020 budget for programs aimed at helping people suffering homelessness to get shelter and help. And in May, he announced the formation of a task force to study and propose solutions to homelessness.

While the state seeks solutions to the larger issue, the effort to secure water and sanitation for unsheltered people for now is being driven at the community level. Sandra Lupien, a policy consultant who worked on the human right to water and sanitation on behalf of Environmental Justice Coalition for Water in Sacramento, said much of the current response is primarily complaint-driven and focused on increasing access to toilets. Access to drinking water “is a less visible problem and is treated with much less urgency” than lack of access to sanitation, she said.

While the state seeks solutions to the larger issue, the effort to secure water and sanitation for unsheltered people for now is being driven at the community level. Sandra Lupien, a policy consultant who worked on the human right to water and sanitation on behalf of Environmental Justice Coalition for Water in Sacramento, said much of the current response is primarily complaint-driven and focused on increasing access to toilets. Access to drinking water “is a less visible problem and is treated with much less urgency” than lack of access to sanitation, she said.

The state, she said, should establish minimum standards for access to water and sanitation and create ways to require local communities to comply. A good place to start, she said, is the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees standards, which require one water tap per 80 people, one shower per 50 people and one toilet for every 20 people.

Portable restrooms, Lupien said, are not the long-term solution.

“They are unpleasant to use, are difficult to maintain on an ongoing basis and they can be easily tipped over,” she said. “I think everyone knows they are just a Band-Aid.”

State water agencies are not shying away from the issue. The State Water Resources Control Board and the California Department of Water Resources are engaged and looking for answers.

“It’s easy to take access to sanitation for granted when we are talking about toilets, toilet paper, water, soap for handwashing and showers. But a lot of people around the state don’t have that access,” the State Water Board’s Max Gomberg, a climate and conservation manager, said at the April workshop.

The state’s interest in solving the problem is tied in part to its responsibility under the human right to water law, the 2012 measure that says every person has the right to safe, clean, affordable and accessible water for drinking, cooking and sanitation. Advocates say sanitation should be a coequal component of the law and that minimum standards for access to drinking water and sanitation are needed for those without shelter.

The state’s interest in solving the problem is tied in part to its responsibility under the human right to water law, the 2012 measure that says every person has the right to safe, clean, affordable and accessible water for drinking, cooking and sanitation. Advocates say sanitation should be a coequal component of the law and that minimum standards for access to drinking water and sanitation are needed for those without shelter.

“There is a clear link between access to sanitation and local surface water quality,” Feinstein, with the Pacific Institute, said at the workshop. “We have these two goals, both to achieve clean surface water and the human right to water. Are they linked? Can we be achieving co-benefits through a targeted set of interventions?”

Tracing High Bacteria Levels

The connection between homeless camps and environmental impacts manifests itself in obvious ways, such as trash, and more subtly through the perceived impact on water quality. Whether and how much human waste from homeless encampments contributes to elevated bacterial levels in surface water is a subject of ongoing investigation in several parts of the state, including the Santa Ana River. Initial results show no clear link between elevated levels of bacteria and homeless camps.

“We have seen high levels of bacteria, but this was expected since it coincided with large precipitation events,” said Phillip Gedalanga, assistant professor at California State University, Fullerton, who has been conducting analyses of water samples from the Santa Ana River. “Our current methods are just unable to differentiate between different types of human sources to be able to say with confidence that the signal, if present, is due to homeless, recreational or wastewater discharge activities. We are hoping to develop a method that can do these things, but we are still in the very early stages of development.”

In San Diego, the Regional Water Quality Control Board launched an investigation in early June into the sources of human waste in the San Diego River and its tributaries after monitoring revealed high concentrations of fecal matter in 12 locations during storms in 2016 and 2017. Homeless encampments were among the suspected sources.

In Northern California, homeless activity along the American River near Sacramento was the suspected cause of elevated bacteria levels in 2017, but no verdict has been reached.

The impacts of homelessness “might be a conclusion someone could jump to, but we are trying to take a much more scientific approach to try and determine if that is really the source,” said Christoph Dobson, director of policy and planning with the Sacramento Area Sewer District.

The impacts of homelessness “might be a conclusion someone could jump to, but we are trying to take a much more scientific approach to try and determine if that is really the source,” said Christoph Dobson, director of policy and planning with the Sacramento Area Sewer District.

Dobson’s agency is working with the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board and others in a collaborative effort to develop a monitoring framework.

“We don’t think we are causing the problem, but anytime you find indicator bacteria, one of the possible sources could be the sanitary sewer system,” he said. “We are either going to find out there’s a problem somewhere, in which case we can solve that problem, or it’s not the sewer and that excludes us from being the source. For us it’s a win either way.”

Some water agencies also are looking to determine how encampments of homeless people affect riparian and aquatic habitat. In February, for example, the Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority (SAWPA) hired a consultant to assess the impact of homeless encampments on water quality and riparian and aquatic habitat in the upper Santa Ana River Watershed. Results are expected by the end of the year.

‘A Big Burden’

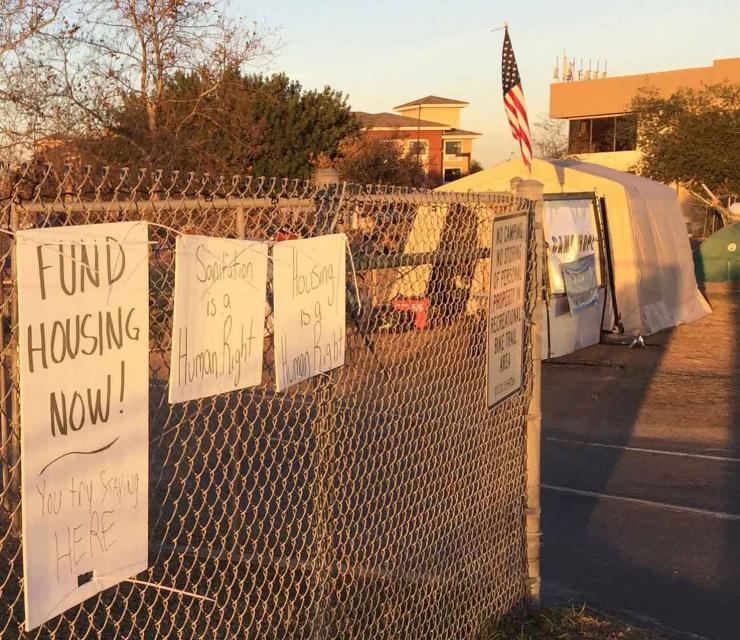

Advocates for improved access to water and sanitation for homeless individuals say action is needed to address what has been deemed a crisis.

“For those 91,642 Californians who spend nights on streets, in parks, or in vehicles, accessing toilets and clean water for drinking and bathing is a daily struggle — one that not only undermines their health, safety, and dignity, but violates their human right to these basic necessities,” said a 2018 report, Basic & Urgent: Realizing The Human Right To Water & Sanitation For Californians Experiencing Homelessness.

“It’s clear that people experiencing homelessness today are shortchanged in terms of access to water, sanitation and hygiene in the state right now.”

~Laura Feinstein, senior researcher with the Pacific Institute

Authored by the Environmental Law Clinic at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Environmental Justice Coalition for Water, the report, among other things, calls for ways for new developments to include publicly accessible drinking fountains and toilets.

“Unless they have lived the experience of homelessness, decision-makers, department directors, program managers and service providers cannot fully fathom the daily reality of living without ready access to potable water, showers, and safe and clean restrooms,” the report said.

James Lee “Faygo” Clark, a homeless man living in Sacramento, said that most days he walks at least a mile to find an establishment that has an open bathroom policy.

“Most times there are no other options,” he said at the Environmental Justice Coalition for Water’s February webinar, “California’s Human Rights Crisis.” “It’s really a big burden.”

Clark, who said he’s been homeless for 17 years, said in an interview that Sacramento has “zero accessibility” to water and sanitation. Some homeless people, he said, carry pliers to crank open water faucets for a drink. Businesses that allow homeless people to use the facilities for water and restrooms “are basically doing the city’s job,” he said.

“There’s almost no public restrooms and very few water fountains,” he said. “The ones that do exist have been shut off, which makes it very problematic for people.”

Suzette Shaw, an advocate for water resources on Los Angeles’ Skid Row, said water and sanitation are basic human necessities. Yet, too many people want to overlook the struggles homeless people endure to get access.

“We have to be cautious of being reactionary and instead be proactive,” she said at the State Water Board’s April workshop. “We have to be conscious of the fact [that] this is a right for all people and as gentrification and urbanization is going on … we have to create spaces for the most marginalized.”

About 9,000 people are homeless on a given night within Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties, with many of them camped along the Santa Ana River and its tributaries, according to SAWPA.

SAWPA has been looking into the nexus between water and homelessness and has identified flood protection, water quality, sanitation/health, riparian and recreational areas and the human right to water as the issues for which innovative solutions are needed.

Mike Antos, SAWPA’s former senior watershed manager, said at the April State Water Board workshop that SAWPA’s examination of the disadvantaged communities, economically distressed areas and underrepresented communities in its four-county region uncovered the need to consider the homeless population.

“This became a key intervention in our region not only because it allowed us to think about homelessness, but also to think about those experiencing homelessness together as a group,” said Antos, now senior integrated water management specialist with Stantec Consulting. “It also gave us the idea of thinking about … whether our policy structures allow us to recognize a community that isn’t necessarily bounded by a census tract or political geography,” the typical means of identifying disadvantaged communities.

There must be “a holistic approach that ensures unsheltered Californians access to water and sanitation … even as efforts to house people permanently continue and expand.” ~

the 2018 report, ‘Basic & Urgent: Realizing The Human Right To Water & Sanitation For Californians Experiencing Homelessness’

Some of the logistics of homeless encampments are being addressed by the Clean Camp Coalition in Riverside County, an initiative of Inland Empire Waterkeeper and homelessness service providers, which distributes trash bags and offers a regular pickup schedule for people living along a stretch of the Santa Ana River. Waterkeeper is a nonprofit group dedicated to enhancing and protecting the Upper Santa Ana River Watershed.

Waterkeeper’s Associate Director Megan Brousseau said talking with homeless people about the service has markedly reduced the amount of trash, established a level of trust and even resulted in people living along the river removing legacy trash from the area. The previous approach of cleaning encampments after people were evicted was not working and “wasn’t smart,” she said.

One of the barriers, she said, is convincing government agencies and the public that providing trash pickup, water and sanitation services to those experiencing homelessness isn’t enabling them but recognizing the need to address an immediate problem. Furthermore, there is awareness among the homeless of the responsibility that accompanies efforts such as providing portable toilet services.

“They say, ‘We are just as much a community and a neighbor as you are and we will self-regulate,’” Brousseau said.

Some cities are taking control of the problem. In Oakland, which has an estimated population of more than 2,700 unsheltered people on a given night, the city provides portable toilets, wash stations and mobile showers in addition to regular trash pickup. The ongoing effort acknowledges that people experiencing homelessness need help while they try to get into permanent housing.

“We have to be realistic; we can’t move people,” said Talia Rubin with the city of Oakland, at the State Water Board workshop. “We don’t have enough housing for folks so let’s make this a positive coexistence and reduce the harm for everyone.”

She said more must be done to provide “brick-and-mortar” solutions that provide homeless people with access to drinking water. That means working with water agencies to build a relationship with them and establish a “buy-in.”

Raising Awareness

Providing water and sanitation to those in need requires a commitment of time, resources and funding. The extent to which the human right to water law leverages that effort remains to be seen. Lupien, the lead co-author of the Basic and Urgent report, said people experiencing homelessness must be a part of the conversation.

“It’s really critical to go into communities and hear from them about what they experience, what they need and the types of approaches that are helpful and effective,” she said.

“It’s really critical to go into communities and hear from them about what they experience, what they need and the types of approaches that are helpful and effective,” she said.

The broader challenge is getting past the stigma associated with homelessness and creating a sense of caring among the public and elected officials.

“We don’t have a compassion pill that we can give people, but what we do have are the public agencies tasked with addressing this problem along with the community-based, nongovernmental organizations,” Lupien said. “And they’ve got to ensure people experiencing homelessness are included in planning solutions.”

While advocates seek to raise greater awareness of the plight of the homeless, efforts are ongoing to ensure that the basic needs of the homeless are met. “It is incumbent on planners, service providers, and decision-makers to break free from the current paradigm that holds as mutually exclusive the notions of moving people into permanent housing and providing for their immediate water and sanitation needs,” the Basic and Urgent report said.

Instead, there must be “a holistic approach that ensures unsheltered Californians access to water and sanitation … even as efforts to house people permanently continue and expand.”

What may be missing in the discussion, some say, is a sense of urgency.

“If we were discussing 100,000 Californians who were unsheltered because the Big One just rocked Southern California … we would not be challenged for very long on how to provide them drinking water and sanitation,” Antos said. “We would have structures in place, or we would invent structures to get it done really quick.”

“If we were discussing 100,000 Californians who were unsheltered because the Big One just rocked Southern California … we would not be challenged for very long on how to provide them drinking water and sanitation,” Antos said. “We would have structures in place, or we would invent structures to get it done really quick.”

Establishing trust and cooperation with people is just as important as the financial support that builds water and sanitation infrastructure. Clark, the homeless Sacramento resident, said “One of the best approaches I’ve seen is literally just engaging people, treating them like human beings” and ensuring city council members stay aware of the problem.

“The raising awareness part is crucial because nothing changes if people aren’t aware of what’s happening,” he said.

Efforts such as the Clean Camp Coalition appear to be a step in the right direction.

Brousseau with Waterkeeper said the outreach succeeds beyond trash cleanup, extending into building relationships and trust with those who are homeless.

“This relationship, or social capital,” she said, “allows us to gain feedback that will guide decisions as to what type of sanitation and water resources will work for them and where to best place these things.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.