A Colorado River Veteran Takes on the Top Water & Science Post at Interior Department

WESTERN WATER Q&A: Tanya Trujillo brings two decades of experience on Colorado River issues as she takes on the challenges of a river basin stressed by climate change

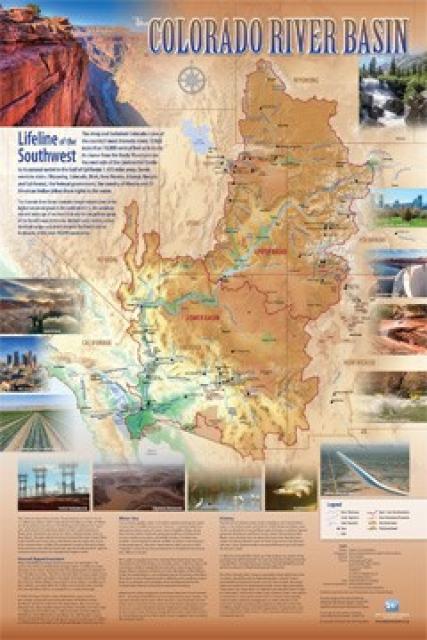

For more than 20 years, Tanya

Trujillo has been immersed in the many challenges of the Colorado

River, the drought-stressed lifeline for 40 million people from

Denver to Los Angeles and the source of irrigation water for more

than 5 million acres of winter lettuce, supermarket melons and

other crops.

For more than 20 years, Tanya

Trujillo has been immersed in the many challenges of the Colorado

River, the drought-stressed lifeline for 40 million people from

Denver to Los Angeles and the source of irrigation water for more

than 5 million acres of winter lettuce, supermarket melons and

other crops.

Trujillo has experience working in both the Upper and Lower Basins of the Colorado River, basins that split the river’s water evenly but are sometimes at odds with each other. She was a lawyer for the state of New Mexico, one of four states in the Upper Colorado River Basin, when key operating guidelines for sharing shortages on the river were negotiated in 2007. She later worked as executive director for the Colorado River Board of California, exposing her to the different perspectives and challenges facing California and the other states in the river’s Lower Basin.

Now, she’ll have a chance to draw upon those different perspectives as Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Water and Science, where she oversees the U.S. Geological Survey and – more important for the Colorado River and federal water projects in California – the Bureau of Reclamation.

Trujillo has ample challenges ahead

of her. For two decades, drought – fueled in no small part by

climate change – has gripped the Colorado River Basin, starving

the huge reservoirs of Lake Powell and Lake Mead of runoff.

Drought plans in place since 2019 failed to stop the decline of

these critical reservoirs. New operating guidelines for the river

are now being discussed and the Basin’s 30 tribes, which have

substantial rights to the river’s waters, want to make sure they

get a seat at the negotiating table.

Trujillo has ample challenges ahead

of her. For two decades, drought – fueled in no small part by

climate change – has gripped the Colorado River Basin, starving

the huge reservoirs of Lake Powell and Lake Mead of runoff.

Drought plans in place since 2019 failed to stop the decline of

these critical reservoirs. New operating guidelines for the river

are now being discussed and the Basin’s 30 tribes, which have

substantial rights to the river’s waters, want to make sure they

get a seat at the negotiating table.

The Department of Interior faces still other water challenges: For example, in southeastern desert of California, the ecologically troubled Salton Sea has nearly upended past Colorado River negotiations involving drought contingency planning.

Trujillo talked with Western Water news about how her experience on the Colorado River will play into her new job, the impacts from the drought and how the river’s history of innovation should help.

WESTERN WATER: You’ve worked on Colorado River issues for years, both in the Upper Basin (as a member of New Mexico’s Interstate Stream Commission) and Lower Basin (as executive director of the Colorado River Board of California). How is that informing your work now on Colorado River Basin issues?

TRUJILLO: I’m very appreciative of having had several different positions that have allowed me to work on Colorado River issues from different perspectives. As the general counsel of the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission, we were finalizing the 2007 Interim Guideline process [for the Colorado River] and I very much had an Upper Basin hat on at that time. That was also right in the middle of our work in New Mexico on negotiating the Indian water rights settlements with the Navajo Nation. Both the Guidelines and the Navajo settlement work really expanded the notion of flexibility in the Basin with respect to the existing statutes and the existing regulations.

“I’m very appreciative of having had several different positions that have allowed me to work on Colorado River issues from different perspectives.”

~Tanya Trujillo, Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Water & Science

I had a Lower Basin perspective when I was working for the state of California on Colorado River issues with the Colorado River Board of California although I was working with a lot of the same people and there were a lot of familiar legal and operational questions. But for the other half of the job, I was brand new to California and was having to learn the whole Lower Basin perspective from scratch.… It was great just to learn the perspective of the Lower Basin and because there are quite a few challenges just within the Lower Basin that are independent of what’s going on in the Upper Basin.

WW:It’s pretty clear the Colorado River Basin is in trouble – too little snowpack and runoff, too little water left in Lakes Powell and Mead. Are we headed toward a Compact call? Or are there still enough opportunities to protect Powell and Mead and meet obligations to the Lower Basin and Mexico without draining upstream reservoirs?

TRUJILLO: I think in some respects it’s the

wrong way to think about this question…. A better approach

is to focus on the strategies the Upper Basin develop to continue

to protect the water resources and communities and economies that

rely on that water. There’s a lot to build off of.  Going back to the ‘07 guidelines, we were

thinking about building off of the existing regulations that

described the operating criteria. We were thinking about how to

protect those resources in the Upper Basin, even when there is a

drought, even when there is less water that’s naturally occurring

in the system on a continual basis.

Going back to the ‘07 guidelines, we were

thinking about building off of the existing regulations that

described the operating criteria. We were thinking about how to

protect those resources in the Upper Basin, even when there is a

drought, even when there is less water that’s naturally occurring

in the system on a continual basis.

But that translates into concerns about how to protect the system in the context of the lower reservoir levels, including the impact on hydropower generation. Each of the Upper Basin states is carefully watching that not only from a power supply perspective, but because if there’s less [hydropower] production, there’s less funding coming in and the funding supports programs that are very important and beneficial to the Upper Basin, like the salinity control program and the [endangered] species recovery programs in the San Juan Basin and the Colorado Basin.

So I know those are concerns that the states have, to protect the elevations at Lake Powell. And another important concern that we specifically agree on is the need to be very careful with respect to the infrastructure and the structural integrity of the [Glen Canyon] dam itself. We may have to operate the facilities at levels that we haven’t experienced before. So we have no operational experience with how the turbines are going to function – and not only the turbines but also how the structures are going to function if we have to use the jet tubes if the turbines are not available.

WW: So there’s concern about how the structures function in terms of getting water from one side of the dam to the other? Or in terms of the physical structure itself?

TRUJILLO: I’m a lawyer and not going to be opining on the actual engineering situation. But we have lots of people who are working in the Upper Basin and Denver Technical Center who are dam safety engineers and they have not had experience in working at this facility under those low water levels. And so that’s where there’s uncertainty. We don’t know how the structures will function under those conditions and that means that people are concerned about that uncertainty because that’s such a critical piece of the infrastructure. [That is] additional motivation among the Upper Basin states for trying to think proactively about how to make sure that the supply and the flows that extend down to Glen Canyon Dam can be maintained.

WW: Given how drought and climate change have left far less water in the Colorado River than the 1922 Compact assumes, is it time to rethink that Compact? Or do you think the Compact and the rest of the Law of the River has the flexibility to accommodate the current realities? And how?

TRUJILLO: I might take the liberty of quarreling a bit with the context of the question because I think the focus should be a forward-looking focus as opposed to rethinking the situation that existed 100 years ago. Even just looking at the past 20 years, we’ve been able to be very innovative and very focused on continued efforts to improve the [weather] prediction capabilities and continued efforts to make sure we have additional flexibility, additional tools, and additional conservation options that can help us work at a multi-faceted level. There are multiple layers of innovations and flexibilities that we have been able to successfully pull together, and my expectation and hope is that will be the same kind of approach that we will continue to work through.

Tanya Trujillo

- Education: Bachelor’s degree from Stanford University, law degree from the University of Iowa College of Law.

- Current job: Assistant Secretary for Water and Science at the U.S Department of Interior, confirmed by the Senate on June 17, 2021.

- Previous jobs: Member, New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission; Project director with the Colorado River Sustainability Campaign; executive director of the Colorado River Board of California; senior counsel to the U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee; counsel to the Interior Department’s Assistant Secretary for Water and Science; general counsel, New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission.

- Fun Fact: Trujillo notes that she is a proud native of Las Vegas – the other Las Vegas, in northeastern New Mexico.

WW: In July, you toured portions of western Colorado to discuss drought and water challenges across the Upper Colorado River Basin. What did you hear? What did you tell them?

TRUJILLO: That was a great trip. The basis of that trip was a listening session that was co-hosted with the governor of Colorado and our Interior Secretary, Deb Haaland. It was an opportunity to hear updates and perspectives from a wide variety of water users in Colorado…. I personally was able to visit quite a few communities in the West Slope, starting in Grand Junction, and see some of the innovative agreements that are coming together in that area with respect to some upgraded hydropower facilities. So it’s great to have the aging infrastructure issues being addressed in that area.

There is obviously a lot of strong,

productive agricultural communities that are clearly watching

with respect to any drought developments. I was also able to

visit the Colorado River District board meeting and heard a

discussion about the different perspectives relating to support

for additional infrastructure and funding different

infrastructure projects. There was a USGS proposal that was being

approved by the River District, and they were able to really

showcase the tremendous contribution that USGS is able to provide

to some of their cooperative investigations. I also met with

representatives from Northern Water and the Arkansas Valley

Conduit Project, so it was a great opportunity to get an overview

of the many important projects that are underway in

Colorado.

There is obviously a lot of strong,

productive agricultural communities that are clearly watching

with respect to any drought developments. I was also able to

visit the Colorado River District board meeting and heard a

discussion about the different perspectives relating to support

for additional infrastructure and funding different

infrastructure projects. There was a USGS proposal that was being

approved by the River District, and they were able to really

showcase the tremendous contribution that USGS is able to provide

to some of their cooperative investigations. I also met with

representatives from Northern Water and the Arkansas Valley

Conduit Project, so it was a great opportunity to get an overview

of the many important projects that are underway in

Colorado.

WW: Did they tell you anything that surprised you?

TRUJILLO: No, I don’t think so. I have a pretty good base of background with some of the challenges that exist in that area. Maybe one way to sum up that that week of visits is that the broad variety of examples there in Colorado can be replicated in other states as well. It was great to just see a diversity of projects that are that are in place there. I would go back there in a second. It was the first trip for me in my tenure as assistant secretary and it was very informative.

WW: As you know, the Salton Sea has been a festering environmental problem for years, and it threatened to upend California’s participation in the 2019 Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan when Imperial Irrigation District insisted that the sea’s ills needed to be addressed as part of the DCP. What can — or should — Interior and the Bureau of Reclamation do to help find a sustainable solution for the Salton Sea?

TRUJILLO: The Salton Sea has had a long history over the past century and is a dynamic and changing terminal lake. For decades there has been a recognition that the changing conditions at the Salton Sea needed to be addressed. The Bureau of Reclamation, other entities within the Department of the Interior and other federal agencies have been involved in the Salton Sea for many decades.

There are various types of federal

lands surrounding the Salton Sea, the Sonny Bono National

Wildlife Refuge provides a sanctuary and breeding ground for

migrating birds, and Reclamation plays an important role as a

partner with respect to ongoing habitat and air quality projects

in support of the state of California’s Salton Sea Management

Program and the Dust Suppression Action Plan. Reclamation also

works in partnership with Imperial Irrigation District to

implement the Salton Sea Air Quality dust control plan. Since

2016, for example, Reclamation has provided approximately $14

million for Salton Sea projects, technical assistance and

program management. Reclamation and its federal partners

participate in a number of state-led committees and processes,

providing technical expertise on activities related to the

long-term restoration of the sea.

There are various types of federal

lands surrounding the Salton Sea, the Sonny Bono National

Wildlife Refuge provides a sanctuary and breeding ground for

migrating birds, and Reclamation plays an important role as a

partner with respect to ongoing habitat and air quality projects

in support of the state of California’s Salton Sea Management

Program and the Dust Suppression Action Plan. Reclamation also

works in partnership with Imperial Irrigation District to

implement the Salton Sea Air Quality dust control plan. Since

2016, for example, Reclamation has provided approximately $14

million for Salton Sea projects, technical assistance and

program management. Reclamation and its federal partners

participate in a number of state-led committees and processes,

providing technical expertise on activities related to the

long-term restoration of the sea.

Reach Douglas E. Beeman: dbeeman@watereducation.org, Twitter: @dbeeman

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook , Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.