Could Virtual Networks Solve Drinking Water Woes for California’s Isolated, Disadvantaged Communities?

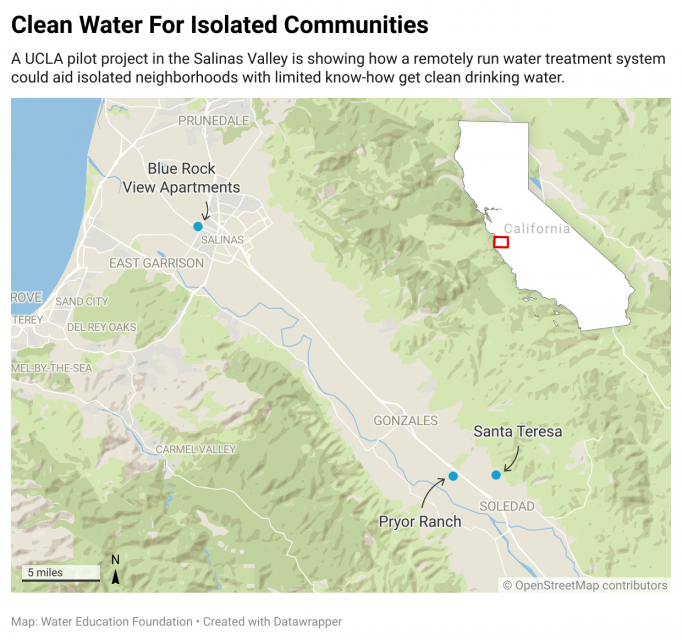

WESTERN WATER SPOTLIGHT: UCLA pilot project uses high-tech gear in LA to remotely run clean-water systems for small communities in Central California's Salinas Valley

A pilot program in the Salinas Valley run remotely out of Los Angeles is offering a test case for how California could provide clean drinking water for isolated rural communities plagued by contaminated groundwater that lack the financial means or expertise to connect to a larger water system.

A pilot program in the Salinas Valley run remotely out of Los Angeles is offering a test case for how California could provide clean drinking water for isolated rural communities plagued by contaminated groundwater that lack the financial means or expertise to connect to a larger water system.

The high-tech system developed by the University of California, Los Angeles removes common contaminants from groundwater, allowing residents of a cluster of Salinas Valley disadvantaged communities to finally turn on their taps without fear. UCLA’s smart systems are smaller and cheaper to implement than traditional water treatment plants and can be operated via smartphone or tablet by an expert located hundreds of miles away.

The aim, said veteran water technologies expert Yoram Cohen at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering, is to create a 21st century fix for communities that are too far to connect to municipal water systems and a viable model that can be deployed across California, where more than 800 water systems are currently failing or at risk of failing.

“We’re really building a permanent solution not just for these remote communities, but really anywhere,” said Cohen. “If this [pilot project] can grow, you would essentially have a virtual water district.”

Thus far the pilot project has produced encouraging results, spurring hope among proponents and state regulators that the technology can become a lasting drinking water solution for other disadvantaged communities.

“There are places certainly in the Central Coast and Central Valley where their physical distance is so far away that this may be the only real long-term option,” said State Water Resources Control Board member Laurel Firestone.

Rich Soil, Tainted Water

The soil in Monterey County’s Salinas Valley is rich enough to produce nearly $4 billion worth of fruits and vegetables each year, but in some areas the quality of water beneath the soil is unsafe for human consumption. The vexing problem is especially common among the isolated apartments and small properties that house the people who grow and pick the county’s famed lettuce, strawberry and vegetable crops.

These remote housing complexes are isolated from municipal water systems and rely solely on groundwater. Too often, the water that gets pumped from domestic wells  and spills out of household taps is tainted with nitrate, a contaminant that gets into groundwater generally from agricultural fertilizers and septic systems.

and spills out of household taps is tainted with nitrate, a contaminant that gets into groundwater generally from agricultural fertilizers and septic systems.

Groundwater contamination is exacerbated during droughts as there is less rainfall to dilute the agricultural runoff and other contaminants. As a result, high-nitrate water seeps deeper into the soil during dry stretches and ultimately mixes with the groundwater supply. At one of the project sites, the nitrate level of the groundwater is five times above the state’s maximum contaminant level for drinking water.

Pregnant women and infants are especially sensitive to nitrate-contaminated water; short-term exposure can cause methemoglobinemia, or blue baby syndrome, and stillbirths.

“These [Salinas Valley] residents know they have contaminated water and they’re very fearful,” said Maria Kennedy, a water resources consultant who guided interactions between the residents and UCLA researchers.

According to the State Water Resources Control Board, there are more than 300 water systems out of compliance with state water quality standards and nearly 1 million Californians without access to safe drinking water. In Monterey County alone, 20 water systems that serve schools and residents have high levels of contaminants like nitrate, arsenic and cadmium.

Many of California’s disadvantaged communities are in agricultural areas and, because they don’t have the human or financial resources to improve their small water systems, depend on subsidized bottled or hauled water deliveries.

Wireless Meters, Digital Alarms

Conventional solutions exist for these small water systems, but they can be costly and unattainable in many instances. Drilling new wells or building a pipeline to connect to neighboring water systems may not be a realistic proposition for isolated, cash-strapped water systems that have fewer than 15 connections.

In search of a more doable fix, UCLA engineers developed a ready-made system designed specifically to serve isolated disadvantaged communities like the ones scattered across the Salinas Valley.

In search of a more doable fix, UCLA engineers developed a ready-made system designed specifically to serve isolated disadvantaged communities like the ones scattered across the Salinas Valley.

The entire reverse osmosis treatment system is housed on-site in a shed flanked by a series of small tanks. Each system can treat up to 4,000 gallons per day and store enough potable water to cover a small community’s indoor needs for approximately 2-3 days. The residual nitrates and unwanted contaminants removed through reverse osmosis are then discharged into the communities’ septic tanks, where the anaerobic environment renders them safe, according to a 2019 UCLA study.

The concept of diverting the residual stream to the septic tank instead of putting it directly into the ground or paying to send it to a waste treatment center is a benefit of UCLA’s project, said Cheryl Sandoval, supervisor of Monterey County’s drinking water protection program.

“Being able to put it into the septic and have it denitrify and not recontaminate the groundwater is very exciting,” said Sandoval. “It answers one of the big issues of the water treatment [process].”

Wireless water meters track usage patterns and an assortment of sensors, digital alarms and other cyber infrastructure relay real-time water quality data to the UCLA researchers. The systems aren’t monitored by people 24 hours a day, but they can automatically respond to shifting conditions, adjust chemical levels or pressure rates independently and alert operators to potential issues. The UCLA team conducts routine site visits to perform maintenance and has contracted with a water treatment technician to provide other onsite assistance, like repairing valves or pumps.

“The fact that UCLA’s system can remotely operate the treatment plants is a huge boon to delivering safe and affordable drinking water to these small and isolated communities.”

~Maria Kennedy, community liaison

The autonomous nature of the system is what makes it an appealing solution for small rural communities that lack the expertise to monitor or react to problems. Once the system is in place, a state-certified water treatment expert can manage the system remotely.

“The fact that UCLA’s system can remotely operate the treatment plants is a huge boon to delivering safe and affordable drinking water to these small and isolated communities,” said Kennedy, who serves as the project’s community liaison.

After several years of community outreach and discussions with local and state regulators, the first remote water system was brought online at an 11-unit apartment complex on the western edge of the city of Salinas in 2020. Two more followed in early 2022. The systems already have combined to produce more than 1 million gallons of clean water, without any major incidents or delays. The smart systems have eliminated the need for bottled water deliveries at one pilot site, and local and state officials expect to discontinue bottled supplies to the other two communities soon.

“We’re talking about large quantities of water that people are using for all potable uses and they don’t have to worry about whether the water is safe,” said UCLA’s Cohen.

By reducing the need for subsidized bottled water, UCLA’s system could also spare the state coffers. This year, the State Water Board budgeted enough money to provide 22,300 households with bottled water for the next two years at a cost of $75 per month per household. Once a remote system is installed, Cohen estimates monthly operating costs of around $50 per household.

Future Outlook

From UCLA to the State Water Board, the project’s collaborators are enthusiastic about the fledgling water treatment technology. However, a variety of hurdles remain before the systems can be deployed to other places, such as the San Joaquin Valley.

On the regulatory side, Eugene Leung, drinking water treatment technical specialist at the State Water Board, said the state is primarily concerned with whether discharge from the small systems impairs local water quality. So far, data from the pilot sites shows that placing the nitrate-laden residual stream into septic tanks appears to be an acceptable approach.

On the regulatory side, Eugene Leung, drinking water treatment technical specialist at the State Water Board, said the state is primarily concerned with whether discharge from the small systems impairs local water quality. So far, data from the pilot sites shows that placing the nitrate-laden residual stream into septic tanks appears to be an acceptable approach.

State Water Board member Firestone called UCLA’s system promising and noted its potential to treat not just nitrate, but other contaminants like 1,2,3-trichloropropane (TCP), an industrial solvent and degreaser that has turned up in soil fumigants.

“A packaged, remotely operated reverse osmosis treatment system is huge,” Firestone said of the Salinas Valley pilot project. “People have wanted to see these for a long time and this pilot shows there are very real options.”

Whether the pilot program will grow into a mainstream solution depends on whether it can attract financial and other support to help it spread.

Though the pilot program was launched with a $2.5 million grant from the State Water Board to support the science and technology development, there’s no guarantee others interested in adopting the UCLA technology will be so fortunate to get grant funding. There is an upfront cost to have the system installed as well as additional expenses for maintenance and technical support.

“A packaged, remotely operated reverse osmosis treatment system is huge. People have wanted to see these for a long time and this pilot shows there are very real options.”

~Laurel Firestone, State Water Resources Control Board member

Kennedy, who helped the UCLA team communicate with and gain the trust of the Spanish-speaking residents and property owners of the Salinas Valley sites, said scaling up the pilot program will require additional financial support from both state and local governments.

“I don’t think they’re going to have a choice but to support these systems because there’s a lot of small communities in the Central Valley and Central Coast that can benefit from this type of technology,” said Kennedy.

A sunset date for the pilot project hasn’t been set, but Firestone said the State Water Board will help facilitate the search for a permanent operator for the Salinas Valley sites once UCLA is done with the project.

While funding to sustain the treatment sites after the pilot program expires remains up in the air, project proponents hope a government agency will eventually fill the funding void. They note the money state agencies have spent in recent years trying to bolster water supplies. For example, over the last year, the State Water Board issued $270 million in grants for drinking water projects in disadvantaged communities while the Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience (SAFER) drinking water program has provided another $118 million toward clean drinking water fixes.

Firestone said she’s encouraged by the pilot program, but said it’s unclear whether the remote systems are an affordable option for disadvantaged communities. She said the State Water Board is still collecting and analyzing data from the Salinas Valley communities to determine what monthly operating costs will look like.

Still, she noted that future funding for the existing Salinas Valley sites and any others could potentially come from the State Water Board’s SAFER or cleanup and abatement fund.

Planted along the fringes of the Salinas Valley’s productive farmland, UCLA’s smart water treatment technology is proving to be a reliable and perhaps — with adequate funding — cloneable option for disadvantaged communities. Cohen said UCLA is setting the table for a public or private agency to step in and manage the future of the remote water treatment technology.

“The question is where do we go from here,” said Cohen. “We hope we can get enough interest to move these into a permanent solution. We don’t see any reason why not.”

Reach Writer Nick Cahill at ncahill@watereducation.org, and Editor Doug Beeman at dbeeman@watereducation.org.

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook , Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.