Does California’s Environment Deserve its Own Water Right?

IN-DEPTH: Fisheries and wildlife face growing challenges, but so do water systems competing for limited supply. Is there room for an environmental water right?

Does California need to revamp the way in which water is dedicated to the environment to better protect fish and the ecosystem at large? In the hypersensitive world of California water, where differences over who gets what can result in epic legislative and legal battles, the idea sparks a combination of fear, uncertainty and promise.

Does California need to revamp the way in which water is dedicated to the environment to better protect fish and the ecosystem at large? In the hypersensitive world of California water, where differences over who gets what can result in epic legislative and legal battles, the idea sparks a combination of fear, uncertainty and promise.

Saying that the way California manages water for the environment “isn’t working for anyone,” the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) shook things up late last year by proposing a redesigned regulatory system featuring what they described as water ecosystem plans and water budgets with allocations set aside for the environment.

Brian Gray, senior fellow at the PPIC and one of the report’s authors, believes the time has come to manage water in a more holistic and equitable manner.

“The current system of protecting the environment is essentially based on placing limitations on other individuals’ exercise of their water rights,” he said. “We think that over time it has undervalued the ecosystem. That got us thinking about this idea of identifying the ecosystem as holding an interest that is akin to other water rights, the same stature as other water rights.”

The PPIC believes its proposal can be accomplished without taking water away from others simply by making better use of water that’s already earmarked for the environment.

That doesn’t allay concerns from farmers and cities that more water for the environment means less water for them.

In an already oversubscribed system, adding an environmental water right or budget “is sort of like making a game of playing musical chairs even tougher,” said Chris Scheuring, managing counsel for the California Farm Bureau Federation. “There are not enough chairs to go around as it is.

In an already oversubscribed system, adding an environmental water right or budget “is sort of like making a game of playing musical chairs even tougher,” said Chris Scheuring, managing counsel for the California Farm Bureau Federation. “There are not enough chairs to go around as it is.

“We’ve already got a water rights system that allocates scarcity,” Scheuring said. “It is not the water rights system that’s the problem, it’s the scarcity, and so will an environmental water budget and environmental water right address the underlying scarcity and improve the overall supply? I don’t know and would want to know that it would.”

Scheuring’s point was highlighted Feb. 20 when the Bureau of Reclamation announced an initial water supply allocation of 20 percent to its agricultural water service contractors south of the Delta.

Tim Quinn, executive director of the Association of California Water Agencies (ACWA), whose members serve both urban and agricultural users, said he appreciates PPIC’s proposal of using market tools to increase efficiency.

“I think it’s a concept worth looking at,” he said. “I’m stopping short of saying it could work.”

Roger Patterson, assistant general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, echoed Quinn’s comments, saying, “In my view it has some merit. Whether it will go somewhere or not is a different question.”

Patterson, who has held leadership posts with the Nebraska Department of Natural Resources and the Bureau of Reclamation, said his experience with other states’ use of environmental water rights shows the method “can provide flexibility and may even be less controversial” than other water management tools.

- SPOTLIGHT: Putah Creek, Yuba River and environmental water for fish

- EDITOR’S NOTE: A New Era for Western Water

California’s most recent drought highlighted the fragile balance between allocating water for people and for the environment. There is growing recognition that more water has to be kept in reservoirs and in rivers to preserve flow and cooler temperature needs for fish, especially during critical life stages.

The existing water quality apparatus functions in a manner that aims to limit pollutants in rivers while ensuring enough instream flows exist to protect water quality and fish and wildlife. Water rights holders are limited, especially during drought, in the amount of water they can take (including water contractors that rely on exports) and critically dry years affect people across the state.

“The 2012-16 drought caused unprecedented stress to California’s ecosystems and pushed many native species to the brink of extinction,” according to PPIC’s report, Managing California’s Freshwater Ecosystems: Lessons from the 2012-16 Drought. “It also tested the laws, policies, and institutions charged with protecting the environment.”

Gray with the PPIC said a broad cross section of stakeholders was consulted prior to the report’s preparation and that many people agree the existing framework does not work well.

“People are very frustrated with the current state of affairs,” he said. “They don’t think it’s working either to provide adequate protection and habitat for fish or a reliable water supply. Both sides feel they bear a disproportionate share of the risk of hydrologic and regulatory uncertainty.”

Water systems throughout the state exist on a thin margin, meaning users are subject to inevitable conflict, especially during drought, Gray said. Then there are the federal and state Endangered Species Acts – powerful laws that function in a way that waits until species are in serious trouble before their protections kick in. PPIC believes the goals of its proposal can be accomplished through the existing amount of water dedicated for environmental purposes.

Water systems throughout the state exist on a thin margin, meaning users are subject to inevitable conflict, especially during drought, Gray said. Then there are the federal and state Endangered Species Acts – powerful laws that function in a way that waits until species are in serious trouble before their protections kick in. PPIC believes the goals of its proposal can be accomplished through the existing amount of water dedicated for environmental purposes.

“We think the amount of water that should appropriately be assigned or dedicated to ecological services should be well-defined,” Gray said. “It should be defined as a budget and it should function as a water right.”

Protections for the environment have been growing since the landmark Clean Water Act was enacted in 1972. Twenty years later, the Central Valley Project Improvement Act dedicated 800,000 acre-feet of water annually to the restoration of anadromous fish in the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, their tributaries and the Delta. Last year, an attempt was made in Colorado to establish legal “personhood” for the Colorado River before the motion was withdrawn by the proponents. If pursued, the case would have been the first federal lawsuit seeking to establish legal rights for nature in the United States.

“What the plaintiffs in that case were trying to do is … use the principles of personhood … to have the courts establish certain rights that then will affect water diversions and water use,” Gray said. “I’m not saying that is necessarily bad,” but he said there are more straightforward ways to bolster environmental protection.

One of the pillars of legal protections for the environment is the Public Trust Doctrine, under which the state retains supervisory control over the diversion and use of water to protect public trust uses in navigable waters, including recreation, environmental values and fish and wildlife habitat. The Public Trust Doctrine also protects fish in non-navigable water. In its decision-making, the State Water Resources Control Board must consider protection of the public trust while also balancing all uses of water, a difficult task considering the many competing demands.

One of the pillars of legal protections for the environment is the Public Trust Doctrine, under which the state retains supervisory control over the diversion and use of water to protect public trust uses in navigable waters, including recreation, environmental values and fish and wildlife habitat. The Public Trust Doctrine also protects fish in non-navigable water. In its decision-making, the State Water Resources Control Board must consider protection of the public trust while also balancing all uses of water, a difficult task considering the many competing demands.

In the 1980s, decisions by the California Supreme Court and a state appellate court ultimately directed the State Water Board to amend the city of Los Angeles’ water rights to protect Mono Lake and its tributary creeks. In 1994, the State Water Board issued its “Mono Lake Decision,” which determined that the Public Trust Doctrine was relevant in the reconsideration of the allocation of the waters of the Mono Basin.

Gray and others believe the present system is not protective enough, given the dire straits for species such as Chinook and coho salmon, and that a new course of action is needed.

“We think the public trust values and ecosystem needs have really been structurally shorted because they are implemented as restrictions or set asides of water and they have a hard time competing with other water right holders,” he said.

Gray acknowledged calling it an environmental water right “raises unnecessary hackles” and that it would be preferable for the idea to be codified in statute by the Legislature.

“Whatever it is called, it needs to function as a water right,” he said. “The manager of the environmental water budget, the ecosystem trustee, must have all the rights and prerogatives that any other water right holder has.”

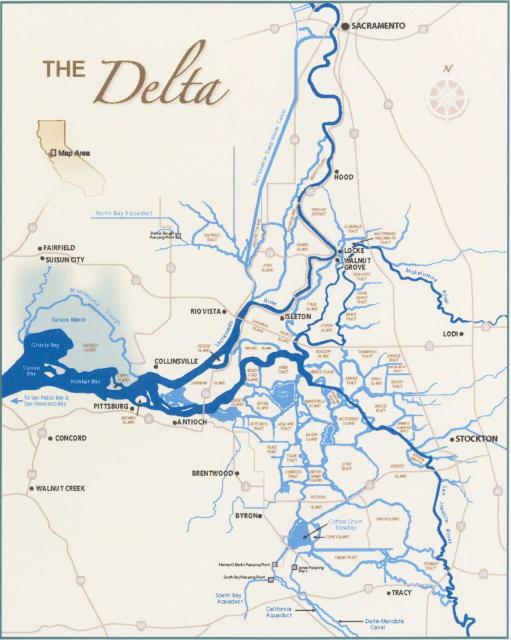

Fisheries advocates have long believed the layer of protection provided by a dedicated block of water would benefit struggling fish species. Curtis Knight, executive director of California Trout, said having enough water in rivers is crucial to maintain temperature controls and limit the salinity that comes with each tide through the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

“The issue of salinity doesn’t get talked about enough,” he said. “In dry years, it creeps up and damages crops and then starts to limit the amount of water that can be pumped from the Delta. It also wipes out important rearing habitat so more water can have a lot of benefits.”

“The issue of salinity doesn’t get talked about enough,” he said. “In dry years, it creeps up and damages crops and then starts to limit the amount of water that can be pumped from the Delta. It also wipes out important rearing habitat so more water can have a lot of benefits.”

Getting a dedicated block of water in place “intuitively makes sense, but then you throw that intuitive idea on the whole water rights system and it just gets so daunting,” Knight said, adding “it seems like it’s the right thing to do, but it’s a tough thing to do.”

Any mention of changing water rights draws concern from water users, particularly farmers, who have been hit hard by drought and must contend with proposed flow regulations designed to protect fish and preserve freshwater levels in the Delta.

“I wouldn’t disagree with anybody that things aren’t working so well right now for the environment, but when you start talking about a whole new demand that’s overlaid … I can’t see how this isn’t a water rights reorganization or something that trumps the existing water rights regime,” said Scheuring, with the California Farm Bureau Federation. “When you talk about operating from the fundamental principle of starting all over and creating an environmental water right of some sort or a water budget for the environment then … my question is, ‘Where does that water come from?’”

The State Water Board’s Plan

Reserving enough water instream for the “reasonable” protection of fish and wildlife is the cornerstone of the first phase of the State Water Board’s proposed updated water quality plan for the Bay-Delta. The plan has garnered much criticism for its requirement that a budget or block of water equivalent to 30 percent to 50 percent of the unimpaired flow of the Stanislaus, Tuolumne and Merced rivers, all of which flow into the San Joaquin River and eventually the Delta, be managed for instream beneficial uses.

Reserving enough water instream for the “reasonable” protection of fish and wildlife is the cornerstone of the first phase of the State Water Board’s proposed updated water quality plan for the Bay-Delta. The plan has garnered much criticism for its requirement that a budget or block of water equivalent to 30 percent to 50 percent of the unimpaired flow of the Stanislaus, Tuolumne and Merced rivers, all of which flow into the San Joaquin River and eventually the Delta, be managed for instream beneficial uses.

Initially, 40 percent of the impaired flow would be required, but this amount may be adjusted, taking into account current information, to protect fish and wildlife, according to the State Water Board. The increased flows also would help meet salinity standards in the southern Delta. Water agencies serving people and farms affected by the proposed rules have blasted it as an overreach while some environmental advocacy groups believe the proposal is insufficiently protective of fish and wildlife.

Felicia Marcus, chair of the State Water Board, said the PPIC’s proposal is in line with what the board is trying to do, which is “to figure how to get the most benefit out of every drop to deal with all of the objectives – fish and wildlife, agricultural, and other human uses through incentivizing creativity and collective action while we adequately protect fish and wildlife. But we’re looking at more than just how we manage the water part of that and including non-flow actions that fish and wildlife need too.”

“What they’ve proposed is a very fruitful area for a collective discussion about how we manage for ecosystem and human needs in a more holistic and predictable way – bringing everybody together as opposed to the wordplay that has dominated this dialogue and the conflict,” she said of the PPIC proposal. “I also think the fact they have broken out the distinction between water that truly is for the environment and water that is for salinity control … is a really important conversation because well-intended people mistook all of it being for fish and wildlife when it really isn’t.”

“What they’ve proposed is a very fruitful area for a collective discussion about how we manage for ecosystem and human needs in a more holistic and predictable way – bringing everybody together as opposed to the wordplay that has dominated this dialogue and the conflict,” she said of the PPIC proposal. “I also think the fact they have broken out the distinction between water that truly is for the environment and water that is for salinity control … is a really important conversation because well-intended people mistook all of it being for fish and wildlife when it really isn’t.”

The Delta drains water from roughly 40 percent of California. Enough freshwater must flow into the Delta throughout dry months to repel salt water that pushes inland on ocean-driven tides from San Francisco Bay. If there is not enough water in upstream reservoirs to release and repel the salt water, it can contaminate the channels from which water supplies are drawn, not just for the State Water Project and Central Valley Project, but also for Delta farmers and water districts in nearby Contra Costa, Alameda and San Joaquin counties.

Gray said the PPIC’s proposal would be a better approach than the State Water Board’s water quality plan for the Delta.

“We would assign responsibility for managing that environmental water to a trustee and give that trustee the ability to deploy the water, be accountable for deploying the water, the ability to store water, the ability to trade, purchase and sell water and to store some of the ecosystem water underground and have conjunctive use that may be beneficial for groundwater recharge,” he said.

The PPIC cites the Lower Yuba River Accord and the Putah Creek settlements, both of which rely on releases of water stored in upstream reservoirs to provide flows for fisheries, as two templates for how the process could work. PPIC’s report notes that the 2008 Lower Yuba River Accord sets flow targets across a range of hydrologic conditions “that better protects the environment and provides more certainty for water users,” while the Putah Creek example features negotiated agreements from 2000 that “increased certainty and reduced conflict over potential allocations of water.”

Balancing the Tension Between Supply and Demand

Legal experts acknowledge that changing the existing system, no matter the mechanism, is an uphill climb. If the idea is to create a distinct environmental water right, “it would be extremely challenging to implement,” said Eric Garner, managing partner of Best Best & Krieger LLP in Los Angeles.

“The issue comes down to balancing the tension between the inherent uncertainty and science in these complex ecosystems with the need for entities that deliver water to have certainty in terms of building projects and having certainty of supply for their users,” he said.

Determining exactly how much water should remain in all the rivers and tributaries that flow to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta is a constant challenge. Scientific experts note that the answer doesn’t lie with a specific number and that there are many factors to consider regarding the relative health of a Delta ecosystem that has been dramatically altered for more than a century.

PPIC Senior Fellow Jeff Mount said the Endangered Species Act is “a bad management tool because it is what I call ’set it and forget it,’ meaning you set these standards and make the assumption that if they are met all the time, things are going to go great. All the time the system is changing so it doesn’t work well in that regard. We are not managing things as ecosystems; we are managing for specific life stages of specific species, which really puts us in a box.”

In 2010, experts with the State Water Board were asked to recommend a flow criterion for the Delta solely to protect fish. In their report, they noted that “it took over a century to change the Delta’s ecosystem to a less desirable state,” and that “it will take many decades” to put it back together again.

In 2010, experts with the State Water Board were asked to recommend a flow criterion for the Delta solely to protect fish. In their report, they noted that “it took over a century to change the Delta’s ecosystem to a less desirable state,” and that “it will take many decades” to put it back together again.

“While folks ask, ‘How much water do fish need?,’ they might well also ask, ‘How much habitat of different types and locations, suitable water quality, improved food supply and fewer invasive species that is maintained by better governance institutions, competent implementation and directed research do fish need?’” the report said. “The answers to these questions are interdependent. We cannot know all of this now, perhaps ever, but we do know things that should help us move in a better direction, especially the urgency for being proactive.”

Almost 40 years ago, California courts ruled that a water right could not be held for the sole purpose of keeping water within a system to benefit the environment. That decision led to the creation of Section 1707 in the Water Code, which allowed water rights holders to transfer the water they would otherwise be diverting back to instream flows for the environmental benefit.

“Unfortunately, it has been used on such a limited basis, it is easy to overlook,” Garner said. “Clarifying the process and establishing better rules and greater certainty would really help. The State Board has made a little progress, but if the Legislature is going to do something on an ‘environmental water right,’ then making this more workable would be a good place to start.”

More Water for Fish?

As California developed its water diversion, storage and conveyance systems over the decades, the needs of the environment were supplanted as wetlands were drained, rivers dammed and water diverted. Gradually though, the pendulum began to move toward implementing policies to protect the environment affected by the construction and operation of water projects. The court decisions involving Mono Lake were major milestones in that process.

Many people in the environmental advocacy community, however, believe that the playing field is far from level.

“I think at the time there was a lot of enthusiasm with … how public trust and the Fish and Game Code would be used to shape water policy,” said Knight, the California Trout executive director. “I think you could say they have been underutilized and maybe the impact isn’t quite what a lot of people had hoped. Maybe that’s because there’s not enough definition I think that’s where an environmental water right could come in and provide … a specific mechanism to help meet the public trust.”

Mount, with the PPIC, emphasized that what’s being talked about is a better use of the water dedicated for water quality and environmental needs.

“One of our biggest problems in the water community is we don’t believe that the people who manage water for the ecosystem are efficient with what they do.”

~Tim Quinn, executive director, Association of California Water Agencies

“One of the things we apparently didn’t communicate well to some people is this notion of an environmental water budget. It’s not as if you suddenly go out and take water away from people,” he said. “The original asset is the water that is allocated to meet water quality and flow standards. That’s already there. That’s why you can call it an environmental water budget and even have it function like a water right without ever taking a drop away from anybody.”

While there are places in need of extra water for ecosystem and species objectives, Mount said efficiency of use and getting the highest return on investment in ecosystem water is paramount.

“One of the things that we would propose is that you just don’t grant an environmental water budget, but you actually determine pretty high standards for goals and objectives with that water and you have in place the ability to test the efficiency of its use,” he said. “Right now, we don’t do that.”

The notion of efficiency in environmental water allocations is likely to draw skeptical glances from urban water providers, who have long chafed against what they see as arbitrary and, at times, wasteful dedications of water to the environment.

“One of our biggest problems in the water community is we don’t believe that the people who manage water for the ecosystem are efficient with what they do,” Quinn with ACWA said. “If they had market tools that determine where and how water goes, then the way they are using water would have an opportunity cost.”

Economists such as Quinn say the true cost of something is what you give up to get it, otherwise known as the opportunity cost.

Marcus said the State Water Board’s plan seeks “the smartest way to manage this block of water to achieve the purposes and do it in a better way than just a flat percentage of unimpaired flow, but that takes people coming together to manage that block of water in concert with non-flow measures to make a real difference on the ground.

“That piece has been missing in the simplistic talking points about flow only,” she said, adding “we are as much about changing the dynamic to reward action as we are the numbers.”

The State Water Board also needs better and more timely data on water rights and flows “to manage a modern system,” she said.

The Way Forward

Whether the idea of an environmental water right or something like it gains traction remains to be seen. However, the challenge of providing enough water for people and the environment will continue to keep state officials and stakeholders busy for the foreseeable future.

“The Public Trust Doctrine is potentially a very powerful tool that depends largely on litigation to implement,” PPIC’s Gray said. “That’s a document that has great influence, but it’s not well defined to do that, you need to bring a case before the board or before the courts to then define what the public trust means and requires, and what’s the reasonable allocation of water to meet the public trust given the competing demands on the resource. That’s a very time-consuming process and that’s why we have seen relatively few public trust cases.”

“The Public Trust Doctrine is potentially a very powerful tool that depends largely on litigation to implement,” PPIC’s Gray said. “That’s a document that has great influence, but it’s not well defined to do that, you need to bring a case before the board or before the courts to then define what the public trust means and requires, and what’s the reasonable allocation of water to meet the public trust given the competing demands on the resource. That’s a very time-consuming process and that’s why we have seen relatively few public trust cases.”

Scheuring said that most farmers “won’t stand in the way of any truly win-win proposition.” He added, “the key to that here is that it must be developed in a way that’s respectful of existing users.” The question remains of how to allocate water to people and the environment in a way in which the needs of both are met.

“Scarcity is a fundamental problem in a growing California,” Scheuring said. “We have tripled the population that was here when the system was largely built out. In the last generation we have overlaid a network of environmental regulations that have really ratcheted down the system, so it’s the zero-sum problem that any viable long-term solution should address.”

MWD’s Patterson said there is potential in dedicating a block of water for fish and the environment.

“Let’s say that you were successful in securing an instream flow right and have a storage right that goes with that,” he said. “That gives you flexibility to do whatever water users do and you may have conditions where you don’t need water for instream flows for a certain period of time; you could essentially sell it and generate some money … for habitat and get more fishery benefit out of the flow you have.”

Knight and others believe the environmental water right/budget has the necessary flexibility to work.