How Private Capital is Speeding up Sierra Nevada Forest Restoration in a Way that Benefits Water

WESTERN WATER SPOTLIGHT: A bond fund that fronts the money is expediting a headwaters restoration project to improve forest health, water quality and supply

The majestic beauty of the Sierra

Nevada forest is awe-inspiring, but beneath the dazzling blue

sky, there is a problem: A century of fire suppression and

logging practices have left trees too close together. Millions of

trees have died, stricken by drought and beetle infestation.

Combined with a forest floor cluttered with dry brush and debris,

it’s a wildfire waiting to happen.

The majestic beauty of the Sierra

Nevada forest is awe-inspiring, but beneath the dazzling blue

sky, there is a problem: A century of fire suppression and

logging practices have left trees too close together. Millions of

trees have died, stricken by drought and beetle infestation.

Combined with a forest floor cluttered with dry brush and debris,

it’s a wildfire waiting to happen.

Fires devastate the Sierra watersheds upon which millions of Californians depend — scorching the ground, unleashing a battering ram of debris and turning hillsides into gelatinous, stream-choking mudflows.

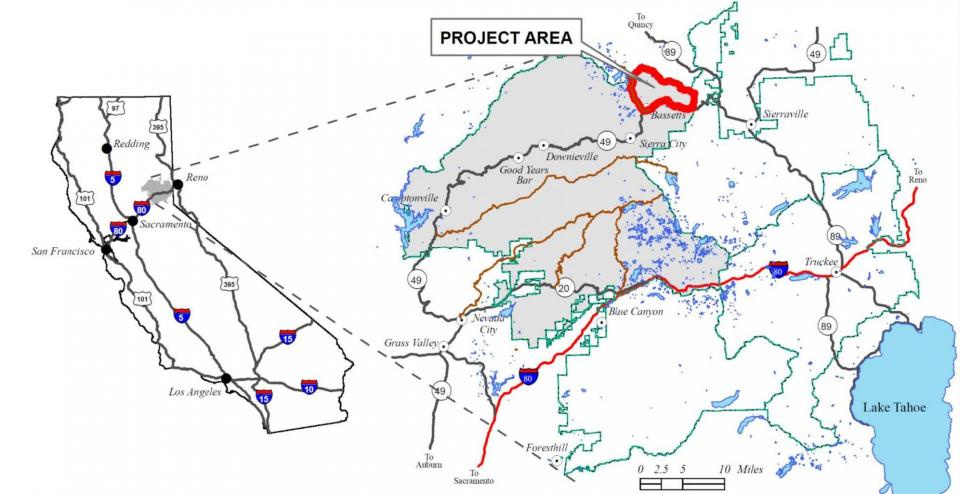

Fixing this crisis scenario could take a decade in any watershed. But in the North Yuba River watershed northeast of Sacramento, the effort has been kicked into high gear thanks to an innovative infusion of public and private sector dollars that fund forest projects with many benefits — including improved water supply.

“You’ve got communities in fire-prone areas and they’re at risk, and frankly our forest is at risk. You lose the forest, you essentially lose the soil. The water isn’t going into the ground, it’s just going to come and go.”

~Tahoe National Forest District Ranger Lon Henderson

“There is a big opportunity to address climate resiliency using money that typically resides in bonds, funds and markets,” said Nick Wobbrock, co-founder of Blue Forest Conservation, an investment firm that has developed the Forest Resilience Bond. The bond is a way for investors to direct private money toward forest restoration work that typically has been slowed by governmental budgetary restrictions or public funds redirected to firefighting.

Said Wobbrock: “There are way more dollars in our pension funds than in our government budgets.”

The project in the North Yuba River watershed has drawn together federal, state and local agencies, including the Yuba Water Agency, which expects that a healthier forest means a firmer and more reliable water supply for the 60,000 acres of irrigated lands it serves in Yuba County.

Step one is thinning an overpopulated landscape to make way for the movement of water. Estimates are that a fully restored forest landscape can increase the water yields by as much as 10 percent in the North Yuba watershed.

“If there are less trees per acre, there is less transpiration and more water available for the soil,” said Willie Whittlesey, the project manager overseeing Yuba Water Agency’s forest initiatives. “That water makes it through the soil into the small tributaries and larger streams and for us, into the North Yuba River and our reservoir.”

The Forest Resilience Bond uses

private capital to finance forest restoration activities.

Beneficiaries, including the U.S. Forest Service and the California Department of Forestry and

Fire Protection, reimburse investors over time. Yuba Water

has pledged $1.5 million toward the project and the state of

California has committed $2.6 million in grant funding, with

additional funding from the

Sierra Nevada Conservancy.

The Forest Resilience Bond uses

private capital to finance forest restoration activities.

Beneficiaries, including the U.S. Forest Service and the California Department of Forestry and

Fire Protection, reimburse investors over time. Yuba Water

has pledged $1.5 million toward the project and the state of

California has committed $2.6 million in grant funding, with

additional funding from the

Sierra Nevada Conservancy.

“The buzz phrase is ‘accelerate the pace and scale,’” said Whittlesey. “Blue Forest and the Forest Resilience Bond are a catalyst for getting this done. This project was already planned by the U.S. Forest Service. It was shelf-ready; they just didn’t have the funds to do it.”

Implementation of the project is being led by the National Forest Foundation, a nonprofit partner of the U.S. Forest Service. Blue Forest Conservation structured the investment and raised $4 million from foundations, impact investors and an insurance company to help complete the estimated $4.6 million project, according to Zach Knight, Blue Forest’s co-founder and managing partner.

Accelerating the Timeline

The aim of the first project undertaken by Blue Forest is to focus on 15,000 acres of forestland in the North Yuba River watershed with tree thinning, meadow restoration, prescribed burning and invasive species management.

The initial 5,000-acre work plan would typically take as long as a decade to complete but is now expected to be done in three years with the help of Blue Forest, said Lon Henderson, a district ranger with the U.S. Forest Service’s Yuba River District.

Blue Forest “brings a fantastic way of expediting the whole process,” he said. “They have changed our whole timeline.”

Typically, projects involve a lag time between contracted work and reimbursement with grant funds. With the Forest Resilience Bond, “that check is immediately available to be written … so if you are a contractor, you know you are going to be paid right away,” Henderson said. That, in turn, increases the number of bidders — boosting competition and lowering the cost.

How It Works

- Investors buy into the Forest Resilience Bond

- The money raised is then used to fund restoration activities, including prescribed burns, forest thinning, invasive species removal and meadow restoration work

- Restoration work funded through the bond is expected to reduce wildfire risk and emissions, improve water runoff, protect water and air quality, revitalize rural economies through jobs, reduce fire exposure to insured assets and protect both habitat and recreational values

- Agencies that benefit from the work pay off the bonds, allowing bond holders to recoup their investment

Henderson said the Yuba River watershed is one of the largest undamaged watersheds in the Sierra Nevada. It’s time to take the necessary actions such as thinning and meadow restoration to protect lives and property, the forest environment and water supply for those downstream, he said.

“You’ve got communities in fire-prone areas and they’re at risk, and frankly our forest is at risk,” he said. “You lose the forest, you essentially lose the soil. The water isn’t going into the ground, it’s just going to come and go.”

“We tell people that when you look at the forest from afar, it’s not going to look much different. There is just going to be less trees per acre.”

~Willie Whittlesey, Yuba Water Agency

The fallout from California’s recent spate of devastating wildfires and the anticipated effects of climate change on watersheds are ushering a revamped approach of forest stewardship.

About 80 miles south of the Yuba River watershed, the state Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund through the California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 is helping to pay for forest thinning as part of an eight-year project that directly benefits Placer County Water Agency’s hydroelectric power operations and water supply. Andy Fecko, the water agency’s director of resource development, said averting catastrophic wildfire protects millions of dollars in hydroelectric infrastructure and protects the water quality of the reservoirs upon which the agency depends.

Placer County Water Agency has several million dollars and contractors on standby every winter to clear debris from the American River, said Fecko, adding that sediment from the 2014 King Fire that burned nearly 98,000 acres continues to flow into Ralston Afterbay.

Furthermore, forest thinning boosts the landscape’s ability to act as a sponge for all the moisture it receives.

“The thing that touches both the water and the energy side is if the sponge doesn’t work … we get all the water in concentrated pulses and are not able to store it and meter it out,” Fecko said.

The Overstocked Forest

The Sierra Nevada’s emerald forest of today looks nothing like it did 100 or 150 years ago, in part because of a management structure that emphasized fire suppression.

“If you are not from here, you say, ‘Wow, that’s a beautiful forest,’ and it is, but it’s not what’s been here historically,” said Henderson. “You’d have a greater variety of trees, less homogeneity and quite a few gaps because of that normal fire-return interval.”

During a 2017 TED talk, Paul Hessburg, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service, said the science behind the need for a new management approach is clear. “If we don’t change a few of our fire management habits,” he said, “we are going to lose many more of our beloved forests.”

Hotter and drier summers and windier conditions have stretched the fire season by as many as 80 days a year, Hessburg said. Prescribed burning is needed to thin trees and consume other fuels.

“We need to restore the power of the patchwork,” he said. “We need to put the right kind of fire back into the system again. It’s how we can resize the severity of many of our future fires.”

Uncontained fires, which have a 1 to 3 percent chance of occurring each year, are devastating in their scale of destruction. The heat is so intense that an organic vapor from burned vegetation clings to soil particles, repelling water and resulting in more runoff and less infiltration, said Kathleen Harrison, a principal geologist with Geosyntec Consultants who spoke June 12 in Los Angeles at a seminar called “Strategizing Against the Flame: What’s Next for California’s Wildfires?”

“The higher the burn severity, the more runoff will occur,” she said.

In addition, a thinned forest is important in the Sierra Nevada, where snowpack means everything for the state’s water supply. Too many trees mean snow lands on treetops and melts before touching the ground.

“You lose water with an overstocked forest,” Henderson said. “The moisture doesn’t make it to the ground and the moisture that does gets pulled up by the overstocked forest.”

A More Resilient Landscape

Chopping down trees can cause an emotive response by the public, but Whittlesey with Yuba Water said it’s important to keep the bigger picture in mind.

“We tell people that when you look at the forest from afar, it’s not going to look much different,” he said. “There is just going to be less trees per acre. We are trying to bring forests back to their pre fire-exclusion condition.”

The goal, he said, is to have a mix

of different densities — some open and more meadow-like and

others that are dense. The result is a watershed that more

efficiently stores and releases spring runoff.

The goal, he said, is to have a mix

of different densities — some open and more meadow-like and

others that are dense. The result is a watershed that more

efficiently stores and releases spring runoff.

“Can we capture and use that water for hydropower generation? Sometime yes, sometimes maybe not,” said Whittlesey. “It’ll spill and make its way to the Delta, but no matter what, it’s going to provide water for habitat all the way from the headwaters into the Delta.”

The Forest Resilience Bond works entirely without revenue from timber sales, although if there were to be a timber sale, that could offset some of the restoration cost, said Wobbrock.

Henderson with the Forest Service said a healthier, more vibrant landscape is the aim.

“I really do want the timber off the landscape, but not for the reason you are going to accuse the Forest Service of,” he said. “It’s to restore a more resilient landscape and the value of the timber we take off goes a long way toward financing the restoration work that needs to be done.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.