‘If You Unbuild It, They Will Come’

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: Scientists Chart Transformation of Klamath River and Its Salmon Amid Nation’s Largest Dam Removal Project

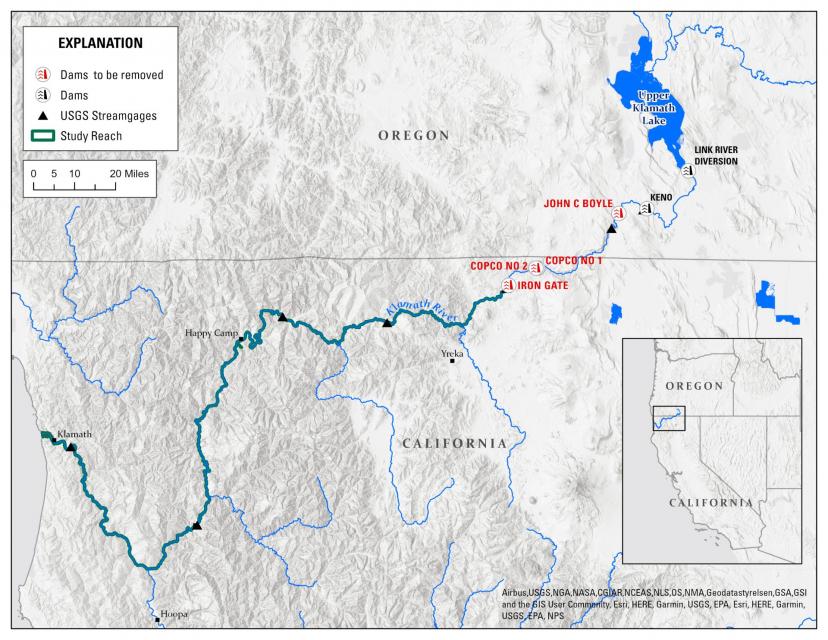

The Klamath River Basin was once one

of the world’s most ecologically magnificent regions, a watershed

teeming with salmon, migratory birds and wildlife that thrived

alongside Native American communities. The river flowed rapidly

from its headwaters in southern Oregon’s high deserts into Upper

Klamath Lake, collected snowmelt along a narrow gorge through the

Cascades, then raced downhill to the California coast in a misty,

redwood-lined finish.

The Klamath River Basin was once one

of the world’s most ecologically magnificent regions, a watershed

teeming with salmon, migratory birds and wildlife that thrived

alongside Native American communities. The river flowed rapidly

from its headwaters in southern Oregon’s high deserts into Upper

Klamath Lake, collected snowmelt along a narrow gorge through the

Cascades, then raced downhill to the California coast in a misty,

redwood-lined finish.

For the past century, though, the Klamath – a name derived from a Native American term for swiftness – hasn’t been free-flowing or flush with salmon. Dams block fish from the upper watershed’s spawning grounds. Reservoirs host toxic algae blooms. Parasites and pathogens that can flourish when dam-regulated flows are low have wiped out salmon by the tens of thousands.

The Klamath’s ecological vitality — above and below the dams — has diminished along with longstanding tribal connections to the river.

Now, after decades of tireless negotiating among myriad parties, the Klamath is being given a chance to return to a more natural state. Construction crews this summer are taking out the first of four essentially defunct hydroelectric dams choking a 64-mile stretch, with the remaining three slated to come out by the end of 2024 in the largest dam removal project ever undertaken.

“A dam removal of this size is unprecedented. Everyone, I would say, is watching this.”

~Sarah Null, watershed sciences professor at Utah State University

But several questions remain: Will the Klamath’s damaged ecosystem recover? How will salmon respond, and can they find their way back above the former dam sites for the first time in more than 100 years? How will the river’s food web change? Will the algae blooms disappear with the reservoirs?

Scientists aren’t exactly sure — a river restoration plan of this size has never been tried — but they are pouncing on the opportunity to find out.

Using techniques and lessons learned from previous dam removals, biologists are studying salmon ear bones to track migratory routes, charting water temperature and chemistry changes and mapping cold water pools salmon use to survive the summer heat.

Native Americans most affected by the dams are on the front lines of the research. Along the river, from its origin in Klamath Falls, Oregon to its mouth near Crescent City, California, basin tribes are tracking fish populations, monitoring water quality and gathering other data across a rugged, remote watershed larger than the states of Vermont and Connecticut combined.

Success on the Klamath River could serve as a blueprint for restoring other watersheds and, proponents say, energize a growing worldwide trend of removing obsolete or seismically unsafe dams.

“We’re now in the age of dam removal, so we’re going to learn a ton out of this,” said Robert Lusardi, a freshwater ecologist with the University of California, Davis, who is tracking watershed changes in collaboration with the Karuk and Yurok tribes. “There’s such a larger purpose here for the science and the work and understanding what dam removals mean for the ecology — and also the people of the Klamath River.”

Removing the dams won’t fully return the Klamath to its natural state. Other major dams on the 263-mile river will remain and growers and communities will continue to take their legal share of its flows. Also, river temperatures are bound to grow warmer with climate change and water quality problems tied to the basin’s legacy of gold mining and logging will linger.

Nevertheless, the world is paying close attention to the remote basin that straddles California and Oregon, eager to see how the dam removals will change the well-being of the river, its fish and the region’s Native Americans who see themselves as part of the Klamath’s ecosystem.

“A dam removal project of this scope is unprecedented,” said Sarah Null, a Utah State University professor who studies the effects of dams on ecosystems and fish diversity. “Everyone, I would say, is watching this.”

Nation’s Biggest Dam Removal Takes Shape

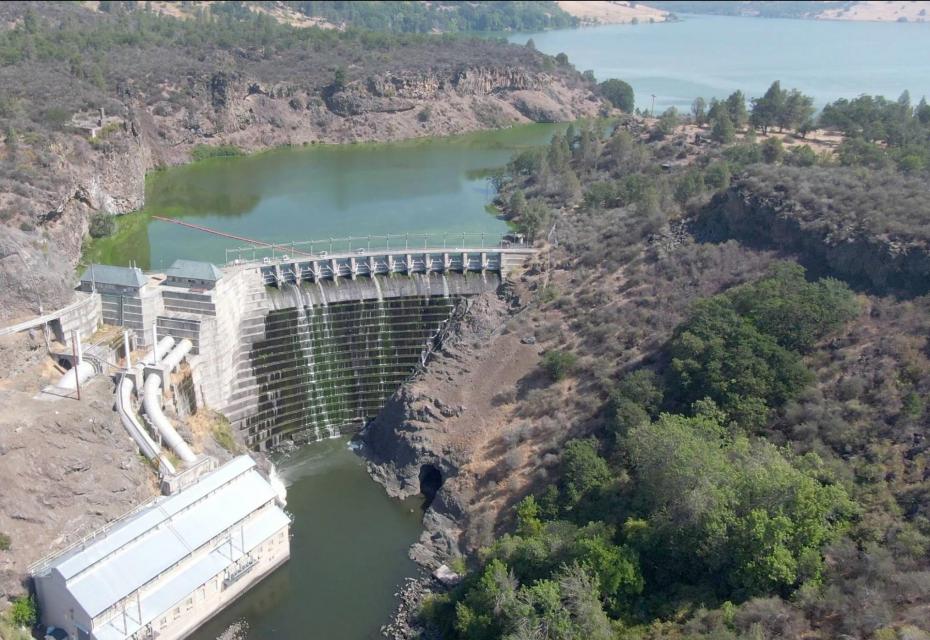

The four dams were built between 1908 and 1962 to generate electricity for the developing agricultural region, but cost concerns and political pressure from tribes and environmental groups ultimately drove the decision to remove them.

The dams’ owner, PacifiCorp,

couldn’t get them relicensed in the early 2000s without spending

at least $450 million on fish ladders and other renovations.

Besides, there was little demand for the electricity, the

reservoirs weren’t designed for irrigation or flood control, and

they were slowly filling with sediment. The Berkshire Energy

subsidiary decided to abandon the federal relicensing process.

The dams’ owner, PacifiCorp,

couldn’t get them relicensed in the early 2000s without spending

at least $450 million on fish ladders and other renovations.

Besides, there was little demand for the electricity, the

reservoirs weren’t designed for irrigation or flood control, and

they were slowly filling with sediment. The Berkshire Energy

subsidiary decided to abandon the federal relicensing process.

A constellation of tribes, environmental groups and fishing interests blamed the dams for “cutting the river in half,” spurring algae blooms and blocking salmon from more than 400 miles of their critical spawning and rearing habitat. They used an unprecedented 2002 disease outbreak on the Klamath that killed more than 34,000 adult salmon to generate public and political support for dam removals.

The Klamath’s salmon populations were sliding toward extinction and removing the dams was the quickest way to arrest the decline of the fish and the tribes’ cultural ties, the groups argued. Since the first power dam was built more than a century ago, an entire run of chinook went extinct and other salmon species have declined by 90 percent.

“We’ve changed the ecosystem to be unfit for a lot of species,” said Alex Gonyaw, senior fish biologist for the Klamath Tribes. “We have seven species that are struggling or are extinct from here and then there’s a lot of others that are holding on but very much struggling.”

In 2016, dozens of parties signed the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement, including the Department of the Interior, the states of Oregon and California, basin tribes and several local governments and irrigation districts.

“We’ve changed the ecosystem to be unfit for a lot of species.”

~Alex Gonyaw, Klamath Tribes biologist

Still, it took several years for PacifiCorp to clear regulatory hurdles and devise a plan that would limit its financial obligations. It ultimately handed control of the dam demolitions and habitat restoration to a newly created nonprofit, the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, which is run by a group of appointees representing Oregon and California, basin tribes and non-governmental organizations. A similar nonprofit was created a decade ago to remove two dams and build a fish bypass around a third impoundment on Maine’s Penobscot River.

Last fall, after negotiations that spanned more than 20 years, the long-held aspirations of tribes and environmentalists became reality. Federal regulators approved a sweeping dam removal plan.

“It’s not the only dam removal but it’s the biggest one so far in terms of complexity, number of dams and positive impact for rivers,” said Brian Johnson, president of the renewal corporation’s board of directors. “We think of it as the start of the biggest river restoration effort that anybody has ever seen.”

The project’s estimated $450 million cost is being covered by surcharges PacifiCorp collected over nine years from customers in Oregon and California and $250 million from Proposition 1, a sweeping water bond California voters approved in 2014.

In June, the dam removal proponents’

efforts began to pay off as heavy machinery started tearing away

the gates and spillway of the smallest dam, Copco No. 2. The dam

will be completely out by September and the reservoir drawdowns

will begin early next year along with the demolition of the three

other dams.

In June, the dam removal proponents’

efforts began to pay off as heavy machinery started tearing away

the gates and spillway of the smallest dam, Copco No. 2. The dam

will be completely out by September and the reservoir drawdowns

will begin early next year along with the demolition of the three

other dams.

The combined height of the four dams is more than 400 feet and up to 15 million cubic yards of impounded sediment will wash down the river toward the ocean. Draining the reservoirs will muddy stretches of the river and may cause short-term water quality issues for fish. However, that is scheduled in the winter when salmon aren’t migrating.

Experts predict the bulk of the sediment will settle in the river system or reach the estuary after two years. This sediment removal approach has been used in other high-profile dam removals without causing major changes to river channels.

Farmer and rancher groups, however, have raised concerns about who will be on the hook for potential unintended consequences the dam removals may cause. They are worried that water from Upper Klamath Lake allocated for farming will be diverted to help flush out sediment or aid habitat restoration.

“If the experts are wrong, the habitat is degraded and anadromous fish stocks don’t recover, our concern is that the water needed to clean up the mess will come at the expense of agriculture,” said Moss Driscoll, director of water policy for the Klamath Water Users Association.

Providing Scientific Clues

Scientists and conservationists see the Klamath dam removals as a rare opportunity to chronicle a large-scale restoration of a watershed.

For the past several years, researchers with government agencies, universities, tribes and non-governmental groups have been gathering information on the river’s current state. After the dams are gone, they will use the data to detect changes in fish migration, water quality, food webs and sediment.

Salmon will be reintroduced to the

formerly dam-blocked stretches of Klamath, and scientists want to

make sure the river habitat has enough deep pools and vegetation

to shelter juvenile fish from predators and hot temperatures.

Healthy rearing habitat in the river is key to salmon survival

and rebuilding the Klamath’s beleaguered native fish populations.

Knowing favored salmon hideouts and rearing areas can help take

the guesswork out of post-dam habitat restoration work.

Salmon will be reintroduced to the

formerly dam-blocked stretches of Klamath, and scientists want to

make sure the river habitat has enough deep pools and vegetation

to shelter juvenile fish from predators and hot temperatures.

Healthy rearing habitat in the river is key to salmon survival

and rebuilding the Klamath’s beleaguered native fish populations.

Knowing favored salmon hideouts and rearing areas can help take

the guesswork out of post-dam habitat restoration work.

One group of researchers believes clues can be culled from the salmon’s ear bones.

Ear bones, or otoliths, taken from salmon carcasses have markings that track a fish’s rate of growth, like tree rings. Researchers have long used otoliths to measure the age of fish, but now a team led by UC Davis’ Lusardi, the Yurok Tribe, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service are using them to map salmon movements.

About the size of a black bean, otoliths have unique patterns that correspond to levels of strontium, a silvery earth metal that seeps into waterways naturally. Researchers measure the percentages of strontium in the otoliths and compare the data with strontium water samples collected throughout the Klamath basin.

“We can understand where salmon rear, how long they rear and what time they leave for the ocean by using this strontium identifier or geolocator,” said Lusardi, who also works for California Trout, a nonprofit group.

Lusardi called the method “pioneering” in relation to dam removal and said the results will help guide habitat restoration work in the Klamath basin and elsewhere.

“We can understand where salmon rear, how long they rear and what time they leave for the ocean.”

~Robert Lusardi, UC Davis researcher, on using earbones of salmon to map their movements

Further up the river in California’s Humboldt and Siskiyou counties, Karuk Tribe biologists are working with Lusardi and Alison O’Dowd, a river ecologist at Cal Poly Humboldt, to track how salmon diets change during and after the dam removals.

Researchers are using carbon and nitrogen isotopes from fish collected by the Karuk to establish baseline salmon diets. The sampling process will continue over the next several years to gauge how a more free-flowing river affects aquatic food webs.

The Karuk Tribe has witnessed firsthand the dams’ devastating effects on salmon as its ancestral territory is just downstream of the lowest hydroelectric dam to be removed. Like the others, Iron Gate Dam was built in 1962 without a fish ladder so it became the final stopping point for sea-run fish.

Toz Soto, Karuk fisheries program manager, said Iron Gate Dam and other dams are largely to blame for the extinction of an entire run of spring-run chinook that once supported a bustling tribal fishery. He said the Karuk Tribe, California’s second largest in enrolled members, is optimistic about the possibility of resuming a salmon fishery once the dams are gone.

“The ability for Karuk tribal people to practice their ceremonies again and harvest spring-run salmon…it’s a big deal,” Soto said. “We’re hoping within a few generations of salmon returns we’ll start to see positive impacts from the dam removals.”

In addition to the dams, the Karuk are trying to document other contributing factors to the salmon decline.

Soto said the tribe has a variety of research projects in addition to food webs, including chinook genotyping, water quality on the Klamath and the Scott and Shasta river tributaries and wildfire effects on fish and hydrology. He predicts the algae blooms that have become emblematic of Klamath reservoirs will happen less frequently once the dams are gone.

The Karuk have looked to a major dam

removal project in Washington state to guide their own research.

The tribe has visited and held conferences with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, which

played a prominent role in the demolition of two

salmon-blocking dams on the Elwha River more than a decade ago.

Soto said the Elwha created a “proof of concept” that the Karuk

and other Klamath basin tribes have tried to implement.

The Karuk have looked to a major dam

removal project in Washington state to guide their own research.

The tribe has visited and held conferences with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, which

played a prominent role in the demolition of two

salmon-blocking dams on the Elwha River more than a decade ago.

Soto said the Elwha created a “proof of concept” that the Karuk

and other Klamath basin tribes have tried to implement.

“There’s a lot of cross-pollination between the two removal efforts,” he said.

Meanwhile, upstream of the dam removals, at the top of the Klamath watershed, the Klamath Tribes and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife are releasing juvenile salmon into the upper basin for the first time since the hydroelectric dams were built.

The Klamath Tribes, whose members include the Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin-Paiute, want to understand how chinook salmon will navigate stretches above the dam that have been blocked for more than 100 years. To do this, biologists implant acoustic tags in young hatchery salmon and release them strategically throughout the upper basin. The goal is to pinpoint areas the fish find hospitable for habitat restoration.

Once salmon and other native fish species like steelhead trout and Pacific lamprey can move back by themselves into the upper basin, they will face a completely altered and, in many ways, impaired ecosystem. One major hurdle is Upper Klamath Lake, the largest freshwater body west of the Rocky Mountains where the river’s headwaters drain in southern Oregon.

Early results have been encouraging. Fish have found their way from the upper tributaries to the southern end of Upper Klamath Lake. The next test is whether fish can withstand the lake’s poor water quality and warm water during the often inhospitable summer months.

“The big question is will they survive Upper Klamath Lake?” said Gonyaw, a Klamath Tribes biologist. “We’ve added (non-native) fish species that weren’t there before, we’ve likely added diseases and we’ve altered the hydrology of the lake.”

After Upper Klamath Lake, salmon will still face a gauntlet of obstacles on their journey to the ocean, including navigating fish ladders on dams that aren’t being removed and predatory fish and birds.

Prepping the Ecosystem

Repairing ecosystem damage caused by humans is important to the ultimate success of the Klamath dam removals.

Habitat work is underway between

Iron Gate and Keno dams, a severely degraded 60-mile stretch

where little research or restoration work has been done compared

with other parts of the watershed.

Habitat work is underway between

Iron Gate and Keno dams, a severely degraded 60-mile stretch

where little research or restoration work has been done compared

with other parts of the watershed.

To help fill the data gaps, researchers are using helicopters equipped with thermal infrared cameras to map cold springs where salmon can still thrive in a warming climate, said Bob Pagliuco, a marine habitat specialist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is responsible for recovery of struggling salmon populations. Little is known about these cold springs because they have been covered by reservoirs over the last century or are on private land largely inaccessible to researchers.

On the ground, Pagliuco’s team is investigating ways to reconnect the Klamath to its floodplains, developing relationships with private landowners and evaluating whether canals and diversions need fish screens. He said more than 25 groups have expressed interest in the 82 projects ranked in a restoration guidebook his agency prepared with Trout Unlimited and the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission.

“Ecological restoration, by its very nature, comes with uncertainties.”

~Trish Chapman, manager of a 2015 dam removal on California’s Carmel River

“There hasn’t been a lot of investment here so it’s kind of fertile ground,” Pagliuco said of the stretch of the river between the four dams being removed. High on the repair list are the Klamath’s tributaries that were drowned by the dam. They must be cleared of the muck the reservoirs leave behind.

The Yurok Tribe is one of the groups restoring the landscape around Iron Gate Reservoir and has recruited an ecologist who headed the Elwha River revegetation in Washington. The tribe is clearing invasive grasses and will monitor changes in stream velocity and water quality. Billions of native plant seeds and thousands of trees such as oaks will be planted across 2,200 acres of previously submerged land.

Reintroducing native species to sites where they haven’t been for decades will deter starthistle, meadow knapweed and other non-native invasive plants from overtaking the riverbanks.

The tribe is also planning habitat work downstream of the dams on the Trinity River, the largest Klamath tributary.

Earlier this year, the Yurok

received a $4 million California state grant to remove mine

tailings and bring back 32 acres of degraded floodplain. The

Yurok hope the

Oregon Gulch Project will provide badly needed juvenile

salmon and steelhead habitat and allow the approximately

one-mile-long river corridor to evolve into a more natural state.

Earlier this year, the Yurok

received a $4 million California state grant to remove mine

tailings and bring back 32 acres of degraded floodplain. The

Yurok hope the

Oregon Gulch Project will provide badly needed juvenile

salmon and steelhead habitat and allow the approximately

one-mile-long river corridor to evolve into a more natural state.

The Yurok Tribe, California’s largest by enrolled members, canceled its commercial salmon fishery in 2023 for the fifth year in a row due to dwindling salmon populations.

“I am confident that we can rebuild salmon stocks through dam removal, habitat restoration, and proper water management, to a level that would support tribal, ocean commercial and recreational fisheries,” Barry McCovey Jr., Yurok Fisheries Department director, said in a statement.

Trish Chapman, who managed the 2015 removal of San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River for the California State Coastal Conservancy, said the restoration challenges will continue after the Klamath dams are gone and that planners must adapt to unforeseen changes.

“Ecological restoration, by its very nature, comes with large uncertainties. For a project to be resilient, you need to account for those uncertainties in the design,” said Chapman, whose agency is helping with the removal of the Klamath dams and Matilija Dam in Ventura County.

‘If You Unbuild it, They Will Come’

In late June, the nonprofit entity in charge of the demolitions released aerial photos showing excavators digging into the core of Copco No. 2. The photos garnered press coverage and were shared on social media, but more importantly they signaled the Klamath project had finally moved out of the planning phase.

The images of yellow heavy machinery

tearing into the dam’s spillway gates prompted a cathartic

release for many who have been fighting for decades to open this

stretch of the Klamath.

The images of yellow heavy machinery

tearing into the dam’s spillway gates prompted a cathartic

release for many who have been fighting for decades to open this

stretch of the Klamath.

“I’m still in a little bit of shock,” said Soto, the Karuk biologist. “This is actually happening…It’s kind of like the dog that finally caught the car, except we’re chasing dam removal.”

Old dams are coming out across the nation and in Europe more frequently than ever before: Last year, 65 U.S. dams were removed in 2022 and a total of 2,025 since 1912. In Europe, at least 325 dams or weirs came down last year alone, according to American Rivers which advocates for and tracks the removals.

Recent history has shown that aquatic species can bounce back quickly once rivers are undammed.

A pair of hydroelectric dams came out on the Elwha River in 2012 and 2014, allowing federally threatened salmon, bull trout and steelhead to approach the river’s headwaters in Washington’s Olympic Mountains for the first time in nearly a century.

Summer steelhead, chinook and coho salmon are no longer fenced out of their spawning areas and have recolonized naturally above the old dams. One species, sockeye salmon, has returned to the Elwha from as far away as Alaska.

“This is actually happening…It’s kind of like the dog that finally caught the car, except we’re chasing dam removal.”

~Toz Soto, Karuk fisheries manager

“If you unbuild it, they will come,” said Sam Brenkman, a National Park Service chief fisheries biologist whose team is monitoring fish populations in 12 major watersheds, including the Elwha.

Brenkman also attributed the recovery to a fishing moratorium on the Elwha that has been in place since 2011.

Klamath proponents are also buoyed by a similar recovery on Maine’s Kennebec River, where large numbers of native sea-run species such as shad, salmon, sturgeon and blueback herring have returned nearly 25 years after the removal of Edwards Dam. The resurgence of the Kennebec fish populations has roundly surpassed biologists’ expectations and many credit the 1999 project with igniting the dam removal trend that continues today.

In California and Oregon, the Klamath project is setting a new bar: “Never before have so many large dams been removed from a single river at one time in the United States,” a Congressional Research Service report states. Many are interested in the project as a proof of concept for other major dam removals.”

You don’t have to look far from the Klamath basin to find other dams that have outlived their usefulness, said Soto, the Karuk fisheries manager. He noted the Wiyot Tribe and others on the nearby Eel River are pushing for the removal of two hydroelectric dams that are close to the end of their lifespans.

“We have set a good example (on the Klamath),” Soto said. “I think the biggest lesson is it takes time and persistence and I think tribes have that. They’re not going anywhere and there’s people who will fight for dam removal and when they’re gone, their kids will fight for dam removal.”

Reach writer Nick Cahill at ncahill@watereducation.org

Know someone who wants to stay connected to water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.