New Lead Scientist Primed for Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta’s Challenges After a Lifetime Surrounded by Water

WESTERN WATER Q&A: Laurel Larsen stresses greater communication and inclusivity in a more nimble Delta science program

It’s perhaps no surprise new Delta

Lead Scientist Laurel Larsen finds herself in the thick of

untangling the many mysteries surrounding the Sacramento-San

Joaquin Delta ecosystem.

It’s perhaps no surprise new Delta

Lead Scientist Laurel Larsen finds herself in the thick of

untangling the many mysteries surrounding the Sacramento-San

Joaquin Delta ecosystem.

After all, Larsen grew up in Florida, where deep, marshy backwaters of the Everglades are reminiscent of the large tidal estuary that is California’s most crucial water and ecological resource. Larsen’s background stirred her interest early.

“I feel drawn to wet environments,” she said. “From the time I was in college, I was really interested in how to more sustainably manage water resources and ecosystems.”

Larsen, an associate professor of geography and civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, was appointed Delta Lead Scientist in April 2020. (She was alerted to the opening by a former student working at the Delta Stewardship Council.) Larsen, who began her three-year term in September, is the seventh person and first woman to lead the program since its creation in 2009.

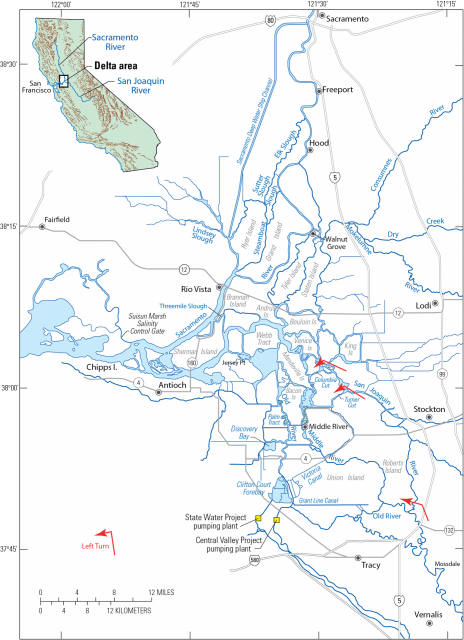

The Delta is a heavily altered, complex ecosystem that is the hub of a water supply network that conveys irrigation water to San Joaquin Valley farms as well as drinking water to two-thirds of California’s population. As Delta Lead Scientist, Larsen oversees a Delta Science Program that is charged with providing the best possible scientific information to inform water and environmental decision-making in the Delta. A key part of that mission is communicating that science to policymakers and decision-makers.

“From the time I was in college, I was really interested in how to more sustainably manage water resources and ecosystems.”

~Laurel Larsen, Delta Lead Scientist

The Delta has confounded water management for decades and questions perpetually abound about the state of the Delta ecosystem. Among emerging issues is the impact that severe wildfires upstream of the Delta in its vast watershed are having on its water quality and potentially water quantity. “We just don’t really have a handle yet on how these increasingly frequent extreme conditions in California are going to impact the Delta,” Larsen said.

Answers are expected this spring via the Delta Stewardship Council’s Delta Adapts program, a climate change vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategy conducted with the Delta Science Program. Emerging issues also will likely be addressed in the 2022 update to the Science Action Agenda, which identifies the science needed to inform management decisions and the major gaps in knowledge. Larsen will guide and edit the updated Science Action Agenda.

In an interview with Western Water, Larsen discussed her goals for the Delta Science Program, the need to think creatively in addressing the Delta’s future challenges and how she hopes to mobilize a more nimble science program to respond to rapidly changing conditions in the Delta.

WW: What attracted you to the position as lead Delta scientist?

LARSEN: As I’ve moved around the country in my professional life, I’ve become interested in restoration applications in a variety of aquatic environments. I went from the Everglades to the Chesapeake Bay to southern Louisiana. Living in the Bay Area, I spent a lot of my recreational time in or around water and started following very closely what was going on in the Delta. And I was able to learn more about that through my teaching a water resources class at Berkeley.

WW: You are the first woman to serve as Lead Delta Scientist.

LARSEN: It’s a

pretty cool feeling and it feels like I’m in good company. There

are so many female leaders in water in California. I just kind of

marvel at some of these executive-level meetings I’m in that are

dominated by women. It feels like there has been a lot of

progress in the right direction but also recognize that this is

the outcome of a really long struggle. I personally feel honored

to be in this position and feel we are moving in the right

direction. It’s why promoting inclusivity, equity and better

integration of social science into the whole scientific ecosystem

is such a priority.

LARSEN: It’s a

pretty cool feeling and it feels like I’m in good company. There

are so many female leaders in water in California. I just kind of

marvel at some of these executive-level meetings I’m in that are

dominated by women. It feels like there has been a lot of

progress in the right direction but also recognize that this is

the outcome of a really long struggle. I personally feel honored

to be in this position and feel we are moving in the right

direction. It’s why promoting inclusivity, equity and better

integration of social science into the whole scientific ecosystem

is such a priority.

WW: You’ve been on the job now since September. What have you learned? What has surprised you?

LARSEN: I am learning so much about this [Delta] system. What strikes me is how much of the Delta science enterprise is dependent upon relationships between the scientific community and stakeholders. There have not been too many negative surprises … but I didn’t realize how far we still have to go as a Delta science community to really integrate social science into all aspects of the Delta science enterprise. We need to listen to and engage and understand a much more diverse group of people.

WW: Which communities are you referring to?

LARSEN: There is a whole body of traditional ecological knowledge about the Delta coming from Native American communities that hasn’t really been considered in our Western approach to science and management of the Delta. We also need to engage people who live and work in the Delta, and scholars and students from historically underrepresented communities.

WW: How would you describe the state of the Delta’s health right now? Is Delta science able to keep up with rapid ecosystem changes?

LARSEN: I don’t have much positive news to report. We are trying to move the system to a healthier level, but it is faced with so many stressors right now. There are stressors of increasing temperatures that are outside the range of tolerance for many of the fish species. Invasive species present challenges. Water quality continues to be a concern with respect to emerging contaminants that we don’t know a lot about yet.

Laurel Larsen

- Age: 38

- Education: Bachelor’s and master’s degrees, Washington University, St. Louis; doctorate in civil engineering (water resources), University of Colorado, Boulder

- Current job: Delta Lead Scientist (three year appointment; currently on leave from the University of California, Berkeley, where she is an associate professor of geography and civil and environmental engineering)

- Previous job: Research hydrologist and ecologist, US Geological Survey, Reston, VA.

- Fun Fact: Larsen swam from the Golden Gate Bridge to the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, a distance of six miles, without a wet suit.

WW: You recently told the Delta Independent Science Board that you want to see nimble, forward-thinking, convergent Delta science? What does that mean?

LARSEN: By nimble I mean having a scientific governance system that can respond rapidly to changing conditions. Let’s say it looks like we’re going into another drought this year. We need to be able to quickly mobilize resources, personnel and agency priorities in order to establish a pre-drought baseline. Then conduct monitoring to determine how drought is impacting various aspects of Delta ecosystem health and our ability to supply water to the rest of California.

In terms of forward thinking, we need to be able to see into the future and anticipate challenges that maybe we haven’t thought about yet. The water quality challenges related to wildfires, the effects of sea level rise and temperature changes. We are working toward doing that … but we need to do it at a scale beyond the Delta Stewardship Council.

WW: You said the Delta Stewardship Council has mostly taken a reactionary approach to issues as a matter of necessity. Can you elaborate on that and explain how it can transition to a proactive approach?

LARSEN: The Delta

Stewardship Council is a fairly young agency. There are aspects

of our mission that are tied to pretty strict deadlines. For a

new organization that doesn’t have a huge amount of personnel or

funding, we did need to be responsive to those deadlines that we

are mandated to meet. We are in a position now where we can begin

looking to the future and think more proactively about how we

think collaboratively about scenarios for future management of

the Delta. We have the opportunity to question the way that we do

science in this rapidly changing world and be creative about

establishing new scientific procedures that are appropriate for

that rapid change.

LARSEN: The Delta

Stewardship Council is a fairly young agency. There are aspects

of our mission that are tied to pretty strict deadlines. For a

new organization that doesn’t have a huge amount of personnel or

funding, we did need to be responsive to those deadlines that we

are mandated to meet. We are in a position now where we can begin

looking to the future and think more proactively about how we

think collaboratively about scenarios for future management of

the Delta. We have the opportunity to question the way that we do

science in this rapidly changing world and be creative about

establishing new scientific procedures that are appropriate for

that rapid change.

We are moving in that direction. One of the other pleasant surprises that I had upon coming on is just how eager people are within the Delta Stewardship Council and our partner agencies to think big and creatively about the future.

WW: What is role of communication between the Delta Science Program and the greater water community and can it improve?

LARSEN: There are places we can improve and one of those is better communication of Delta science to the Legislature. There is good communication to scientists and managers in other agencies within the executive branch but there is a lot of room for better communication to the Legislature.

It is also reaching out to the academic scientific community. My predecessor [lead] scientists were excellent liaisons to the scientific community. What I want to do is take advantage of some of the newer communications formats [Twitter, Instagram, virtual seminars and panels] that are becoming available to us to bring in people from the scientific community who haven’t been doing Delta research already and have skills that could be brought to our common challenges.

“I do have a lot of optimism that we can change the fate of the Delta in a positive way.”

~Laurel Larsen, Delta Lead Scientist

WW: You want to develop a pathway for rapid competitive funding mechanisms. Can you explain what that means and how it would work?

LARSEN: It’s about enacting that nimble science. The idea is that if we have another drought or if it’s a really wet year and there are extreme flooding conditions in parts of the Delta or there is a levee failure, we need to be able to mobilize scientists to understand those effects in a way that can shed some light on management decisions that need to be made relatively soon. It is having a mechanism for funding projects that could respond to these rapidly changing conditions because right now, the funding process is kind of slow. There are a lot of administrative levels that funded projects need to pass through. I am looking into ways to make that whole funding system move a little more rapidly.

WW: What is the biggest unknown about the Delta you want to uncover?

LARSEN: One of the broadest, all-encompassing questions that we have is how we can effectively manage this complex system in a way that promotes resilience in the sense of maintaining the ecological function and maintaining the water supply function. … I do have a lot of optimism that we can change the fate of the Delta in a positive way. We have to do so by acting quickly and really establishing a framework for collaborative, inclusive science now in order to think proactively about the future and plan for it. I think we’re on the right track.

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.