Pandemic Lockdown Exposes the Vulnerability Some Californians Face Keeping Up With Water Bills

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: Growing mountain of water bills spotlights affordability and hurdles to implementing a statewide assistance program

As California slowly emerges from

the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, one remnant left behind by

the statewide lockdown offers a sobering reminder of the economic

challenges still ahead for millions of the state’s residents and

the water agencies that serve them – a mountain of water debt.

As California slowly emerges from

the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, one remnant left behind by

the statewide lockdown offers a sobering reminder of the economic

challenges still ahead for millions of the state’s residents and

the water agencies that serve them – a mountain of water debt.

Water affordability concerns, long an issue in a state where millions of people struggle to make ends meet, jumped into overdrive last year as the pandemic wrenched the economy. Jobs were lost and household finances were upended. Even with federal stimulus aid and unemployment checks, bills fell by the wayside.

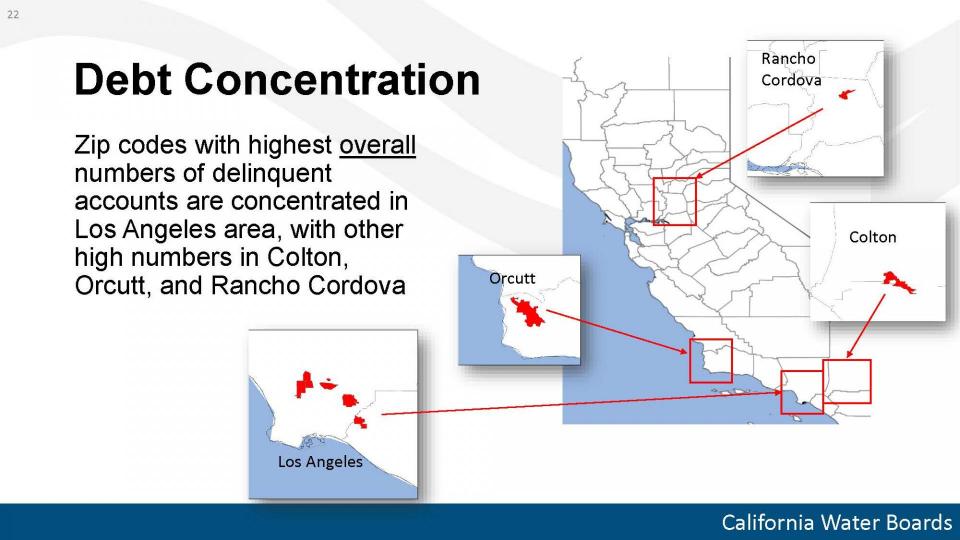

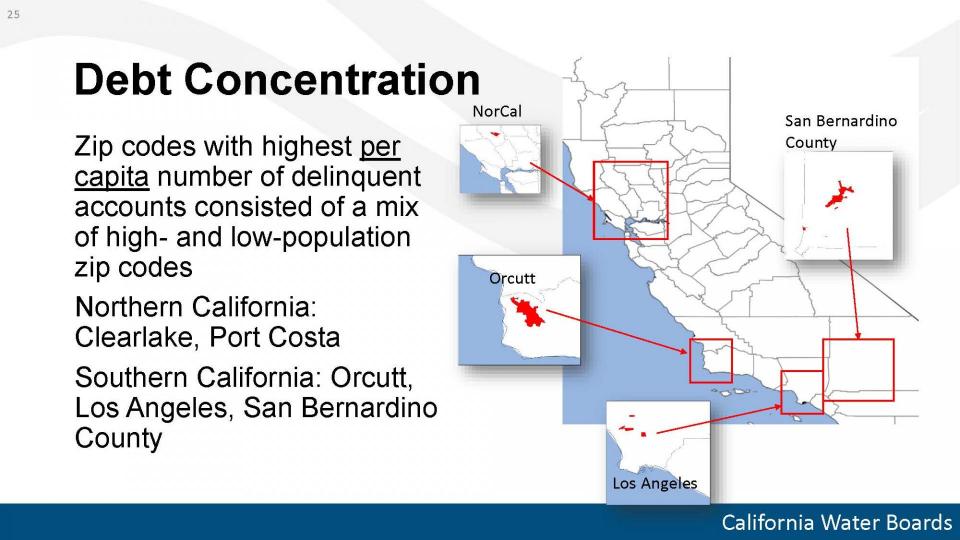

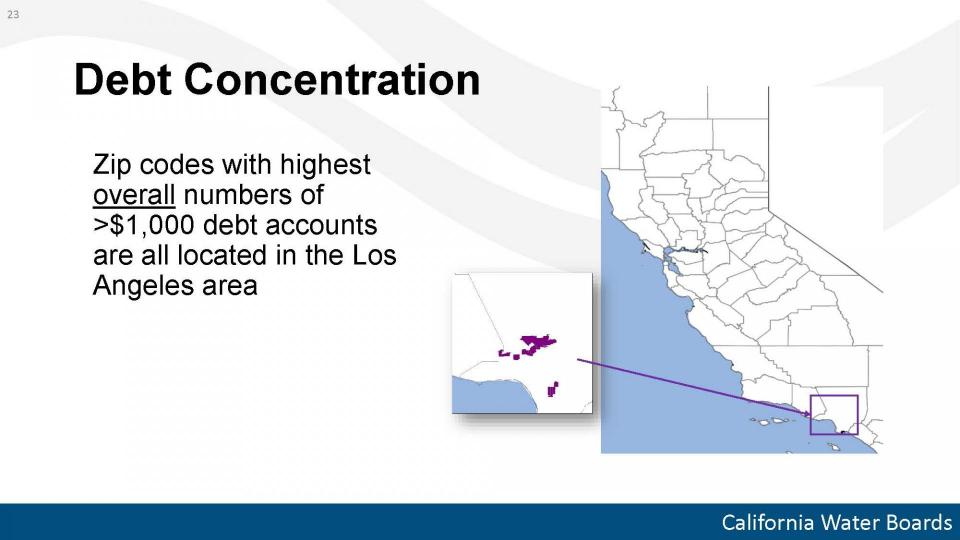

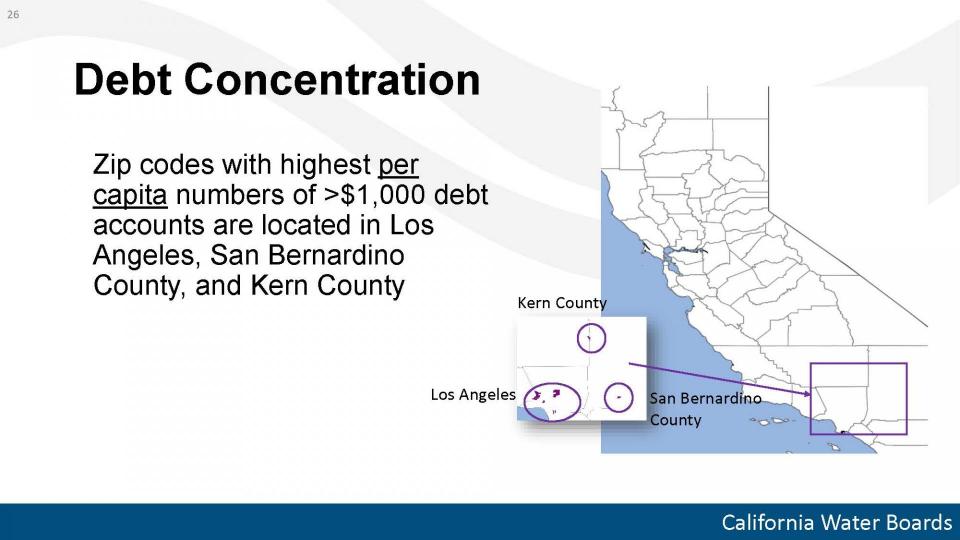

The crisis heightened the financial vulnerability many ratepayers face and spotlighted the larger issue of water affordability. The State Water Resources Control Board, after surveying water agencies about unpaid bills, reported in January that about 12 percent of California households, some 5 million people, are behind on their water bills with an average debt of $500 per household. The figure has grown steadily since then, approaching a collective $1 billion.

Until the state surveyed water systems, “we knew there was crisis, but we didn’t have a sense of the order of magnitude.”

~ Laurel Firestone, State Water Resources Control Board member.

Until the State Water Board’s survey, “we knew there was crisis, but we didn’t have a sense of the order of magnitude,” said Laurel Firestone, a State Water Board member. “I think it reinforces how much of a crisis this is and has elevated the urgency around addressing affordability.”

Despite the mounting water debt, delinquent ratepayers haven’t lost water service thanks to an ongoing statewide moratorium on utility shutoffs during the pandemic. The moratorium was signed by Gov. Newsom on April 2, 2020, to prevent people from losing their water, particularly because of the need to wash hands to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. But the crisis illustrates how unpaid water bills hurt customers and water agencies in different ways.

For water agencies, delinquencies during the pandemic are at a level they have not seen before. “We have this core population that we never had before that would have paid their bills but are not paying,” said Jennifer Bryant, director of administrative service with the Helix Water District in eastern San Diego County. Some, she added, are as many as six bills behind.

The Prop. 218 Hurdle

Solving the short-term problem of mounting COVID-19-related water debt and the longer-term issue of water affordability is complicated. A 1996 voter initiative, Proposition 218, essentially bars public water agencies from using ratepayer funds to pay for a rate assistance program. (Investor-owned utilities, regulated by the California Public Utilities Commission, are not constrained by Prop. 218.)

Some public water agencies, like

Helix, have tapped into creative finance methods to develop

workarounds or temporary programs to offer some kind of aid.

However, 56 percent of Californians have a water service provider

that does not offer rate assistance to low-income customers,

according to the State Water Board. On top of that, some agencies

are reluctant to take on the administrative costs of assessing

customer eligibility, with some enlisting outside social service

agencies to handle that task.

Some public water agencies, like

Helix, have tapped into creative finance methods to develop

workarounds or temporary programs to offer some kind of aid.

However, 56 percent of Californians have a water service provider

that does not offer rate assistance to low-income customers,

according to the State Water Board. On top of that, some agencies

are reluctant to take on the administrative costs of assessing

customer eligibility, with some enlisting outside social service

agencies to handle that task.

Helix, in February, dedicated $500,000 from surplus land sales to fund its assistance program that started in early April. The program, administered by a local nonprofit, offers a one-time credit of up to $300 for single-family residential customers who are behind on their water bills. Bryant said the district doesn’t know how far the money will stretch.

“One question we have is how many people are really in need and how many aren’t paying because they just don’t have to where before they had the threat of a shutoff,” she said. Still, the district’s board wanted to find a legally tenable way to help customers in need.

With Prop. 218, she said, “our hands were tied, which was very frustrating.”

Devising A Rate Assistance Framework

Public water agencies have tough water quality standards to meet and infrastructure to maintain, and those costs get passed on to customers. Many agencies are facing old conveyance systems that are expensive to replace.

There isn’t much budget flexibility. When customers can’t pay, that crimps the bottom line, especially for small water agencies.

“What I’ve seen over time is that for

small water districts, it’s very difficult for them to amortize

costs of water treatment over a small rate group,” said Sen. Bill

Dodd, D-Napa. He is carrying legislation that would create a

statewide low-income rate assistance fund. How it would be funded

is still to be determined.

“What I’ve seen over time is that for

small water districts, it’s very difficult for them to amortize

costs of water treatment over a small rate group,” said Sen. Bill

Dodd, D-Napa. He is carrying legislation that would create a

statewide low-income rate assistance fund. How it would be funded

is still to be determined.

“Everybody needs to pay their water bill,” Dodd said, but no one should be left without water.

In 2015, Dodd authored legislation that required the State Water Board to recommend a framework for a low-income rate assistance program. That report, finalized just before the pandemic hit in 2020, outlined the structure of low-income rate assistance, with possible funding coming from taxes on high personal income earners, bottled water taxes, surcharges on non-eligible households’ water bills or a soda tax.

As it stands, water bill assistance funded by ratepayers only exists for eligible customers of larger investor-owned water utilities, serving 1.4 million California customers but does not exist at public water agencies serving millions more in the state because of Prop. 218. The reaction by California’s public water agency community to a proposal for a low-income rate assistance program depends on how the program is written and funded, said Cindy Tuck, deputy executive director of government relations with the Association of California Water Agencies.

“We think there could be an effective statewide low-income rate assistance program for water, but it needs to be efficient and formulaic so that high administrative costs do not reduce the benefit to low-income households,” she said.

“We think there could be an effective statewide low-income rate assistance program for water, but it needs to be efficient and formulaic.” ~Cindy Tuck, deputy executive director, Association of California Water Agencies.

Details of a rate assistance program matter, Tuck said. “We think it should rely on a state agency that has experience implementing a low-income assistance program,” she said. “Another key piece is that it needs a good funding source that is progressive, not regressive.”

Furthermore, the idea of a public water agency creating a special fund to help low-income or senior ratepayers could raise questions of fairness among other ratepayers, said Bryant, with Helix Water District.

“We can only charge a customer what it costs to provide service to their parcel,” Bryant said. “A low-income program paid with water bill revenue says you have to pay part of your neighbor’s bill if they don’t pay it. That feels a little uncomfortable for some customers.”

Finding Creative Ways to Help

Water bills vary widely in California, based on the source of the water and the extent of water treatment. In some cases, a bill includes charges for electricity, wastewater, stormwater, taxes and fees. Rates are often structured as tiers or blocks. It also depends on the customer. Condominium dwellers with no outside irrigation might pay $20 each month while a 2-acre mansion in the hills of Santa Barbara with lush green grass might pay hundreds of dollars a month.

Customers in the Helix service area typically pay $77.56 per month for their water. In Northern California, ratepayers served by the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) pay about $63 per month.

Some public agencies are better

positioned to help with water rates. In San Francisco, the city

started an emergency assistance program at the beginning of the

pandemic. Paid for in part through the city’s general fund, the

program offers reduced rates for water and sewer services to

qualified applicants. The program, which launched in May 2020,

was set to expire at the end of last year but will now be

expanded through the end of June 2021 and could be extended

again.

Some public agencies are better

positioned to help with water rates. In San Francisco, the city

started an emergency assistance program at the beginning of the

pandemic. Paid for in part through the city’s general fund, the

program offers reduced rates for water and sewer services to

qualified applicants. The program, which launched in May 2020,

was set to expire at the end of last year but will now be

expanded through the end of June 2021 and could be extended

again.

“We hope to take some of the lessons learned from this emergency program – how to make the application process easier, how to reach more customers – and improve our existing discount program so that households still struggling can apply for it,” said Will Reisman with the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission.

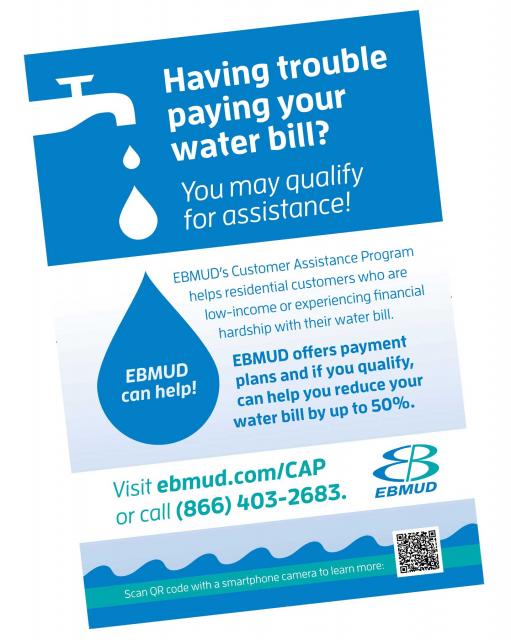

In Alameda County, the pandemic has spurred increased participation in East Bay Municipal Utility District’s long-standing customer assistance program.

“We saw a 20 percent growth in participation in 12 months,” said Andrew Lee, the district’s manager of customer and community services. “Typically, we would see a 4 to 5 percent increase.”

For more than 30 years, East Bay MUD’s customer assistance program has provided eligible customers credit on their water bills, at a maximum of 1,050 gallons per person per month. The program is largely funded from the proceeds of real estate leases the district has with telecommunications providers.

“Fortunately, we do have a pretty good program to create non-rate revenue to fund the customer assistance program,” Lee said.

In Riverside County, Eastern Municipal Water District’s Help2Others program pays $100 of a low-income customer’s water bill, one time in a 12-month period. The program is funded with non-rate revenues, such as income from land leases.

“EMWD partnered with United Way to

assist our customers in the most efficient and sustainable way

possible,” said Amanda Fine, Eastern’s spokeswoman. “United Way

administers the program, so we do not have to possess sensitive

customer information like income data.”

“EMWD partnered with United Way to

assist our customers in the most efficient and sustainable way

possible,” said Amanda Fine, Eastern’s spokeswoman. “United Way

administers the program, so we do not have to possess sensitive

customer information like income data.”

The district offers other programs to help customers in need, such as budget-based water rates where low-use customers pay an extremely low water rate.

Fine said the district notifies customers via phone, email and the postal service to help inform them of payment assistance options. More than 4,000 overdue customers have been called, she said, adding that the district is working to connect customers to Riverside County to apply for funding through the federal 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. The county has paid off $52,800 in customer water bills through the federal program.

For now, financing a low-income rate assistance program means getting creative to find money.

“Whether its excess land lease revenues, cell tower lease revenues or donations, these are not ongoing, sustainable, significant funding sources, but they are the only option available to public systems because they are subject to Prop. 218,” said Max Gomberg, the State Water Board’s water conservation manager who contributed to the 2020 rate assistance report.

More federal relief is on the way, but the $1.1 billion allocated thus far by Congress for water and wastewater assistance is spread across all 50 states and Indian tribes, which means California will have more need than it can respond to. Gomberg said California expects to get about $90 million to help water systems catch up. The state has yet to determine the specifics of the how the funds will be distributed.

One-time state funding is needed quickly to help with the level of water debt that has accrued because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tuck said. ACWA and other statewide associations are urging lawmakers and the governor to dedicate at least $1 billion from the state’s budget surplus to public water agencies and publicly owned electric utilities for that purpose.

Rising Cost of Water

California’s Human Right to Water Law in 2012 sparked a greater recognition that a lot of Californians face challenges in accessing safe and affordable water. Advocates say addressing part of that equation means providing a safety net for low-income residents statewide.

“In many cases the human right to water hasn’t meant enough,” Michael Claiborne with the Leadership Council for Justice and Accountability said on the March 11 Then There’s California podcast. “Progress has been made but there are still far too many Californians that lack access to safe and affordable water.”

According to the State Water Board, adjusting for inflation, the average California household paid about 45 percent more per month for drinking water service in 2015 than in 2007. The burden of that increase “falls disproportionately on the 13 million Californians living in low-income households, many of whom have seen their incomes stagnate during the same period,” the State Water Board’s affordability report said. “The high and rising costs of other basic needs for California residents, including housing, food, and other utility services, mean that cost increases for any single need, such as water, can force families to make difficult and risky tradeoffs which could harm their health and welfare.”

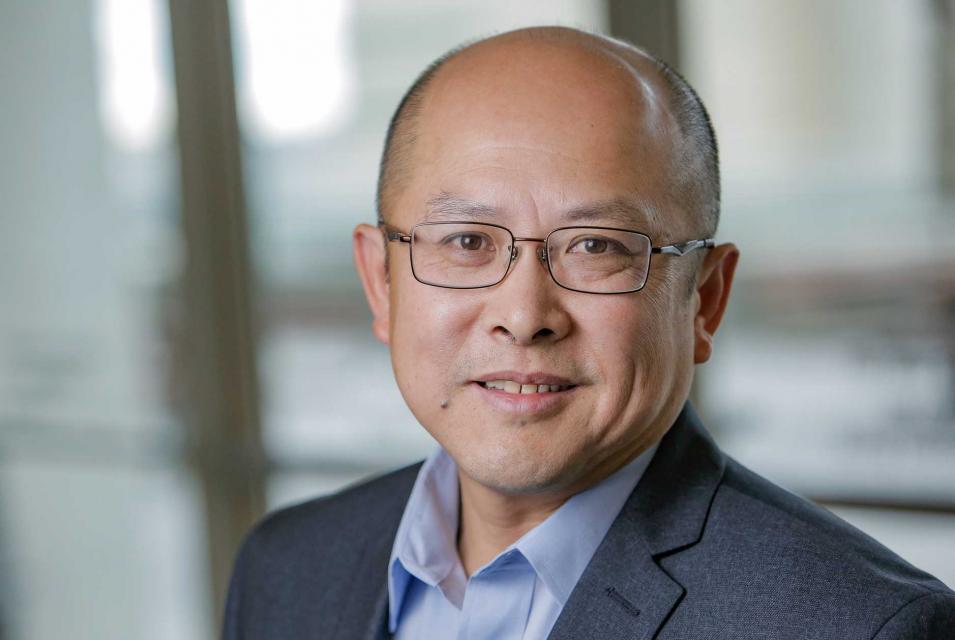

Kurt Schwabe, professor of environmental economics and policy at the University of California, Riverside, said while the 45 percent figure sounds large, it does not convey the complete picture if a rate increase leads to more reliable and/or higher quality water.

That, he said, could be thought of as a bargain over time, though he acknowledged “a bargain to one household may still be a barrier to another household.”

Schwabe’s research, which includes

surveying about 130,000 households in Eastern Municipal Water

District, has shown that while water and sewer service bills are

significantly lower than expenditures on other essential goods

like housing, transportation and health care, they are, as a

fraction of income, much higher for lower income households.

Schwabe’s research, which includes

surveying about 130,000 households in Eastern Municipal Water

District, has shown that while water and sewer service bills are

significantly lower than expenditures on other essential goods

like housing, transportation and health care, they are, as a

fraction of income, much higher for lower income households.

On the water delivery side, public water agencies, particularly small ones, are challenged in keeping water rates affordable when they must comply with ever-tightening water quality standards as well as system upkeep.

“It is a struggle,” said Jim Maciel, board member with the Armona Community Services District in Kings County, south of Fresno. The district has weathered the storm from the pandemic by tapping reserves, and none of Armona’s 1,200 customers have had water service cut off, he said. Fourteen customers owe more than $700 as of March 1, and seven owe more than $1,000. But neighboring water providers are in worse shape. “We’ve got enough of a critical mass that we are able to cover it but not forever.”

Part of the problem, Maciel said, is the requirements for small systems to meet drinking water standards. Many times, the treatment solutions are expensive, even with grant funding. “It’s just very hard for us to cover our costs,” Maciel said.

Water policy experts say a

low-income rate assistance program is one of the most intuitive

ways to make water affordable. Greg Pierce, a researcher at UCLA

and contributing author to the State Water Board report, said

even with rate reform that could offer breaks for low-volume

customers, direct assistance is needed because “there will still

be low-income customers who even the most progressive rates can’t

fully help.”

Water policy experts say a

low-income rate assistance program is one of the most intuitive

ways to make water affordable. Greg Pierce, a researcher at UCLA

and contributing author to the State Water Board report, said

even with rate reform that could offer breaks for low-volume

customers, direct assistance is needed because “there will still

be low-income customers who even the most progressive rates can’t

fully help.”

The State Water Board report said the biggest obstacle faced by existing programs is their limited funding and inability to support households that are most in need. Complicating the issue is that many low-income households live in apartments and don’t pay a water bill directly. In addition, many assistance programs have low enrollment levels and provide insufficient support, the State Water Board’s report said.

Firestone, the State Water Board member, regularly encountered the affordability issue in her prior work with the Community Water Center, the Visalia-based nonprofit she co-founded. “When you are a tiny system,” she said, “it’s just not feasible to have a low-income ratepayer assistance program if all of your 50 customers are low-income.”

Finding A Solution

While the COVID-19 pandemic will eventually recede, paying water bills on time will remains an issue for many Californians.

Pierce, the UCLA researcher, said a robust rate assistance program could have alleviated much of the water debt associated with the pandemic as well as largely avoiding the discussion of halting water shutoffs. He said officials should concentrate in the future on promoting system consolidation, rate reform, low-income assistance and shutoff prevention.

In the meantime, he said, the outstanding water debt will probably be taken care of by making sure higher income customers pay the full amount they owe, increased and extended debt management and partial repayment plans, absorption of lost revenue by utilities and some level of shutoffs due to non-payment.

Uriel Saldivar, senior policy

advocate with Community Water Center, said a low-income rate

assistance program should be available for all who need it, not

just those served by investor-owned utilities. “We don’t want to

have a disparity, we want something universal,” he said.

Uriel Saldivar, senior policy

advocate with Community Water Center, said a low-income rate

assistance program should be available for all who need it, not

just those served by investor-owned utilities. “We don’t want to

have a disparity, we want something universal,” he said.

Saldivar said he believes the opportunity exists to get a bill through the Legislature and signed by the governor. “This really does go across all sectors, all demographics and across the aisle,” he said.

Dodd, the state senator from Napa, said he believes the political will exists to get something done and he’s willing to do what it takes to get his bill through. “I’m an incrementalist,” he said. “Let’s get started, let’s get a fund built up. I’m not asking for any big allocation out of the state budget.”

Firestone said she is optimistic a solution can be reached.

“Doing nothing is not an option,” she said. “Whether we get to a perfect outcome or a clear, long-term outcome, I think we will be establishing programs that haven’t existed before because of the scale and magnitude of the crisis.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.