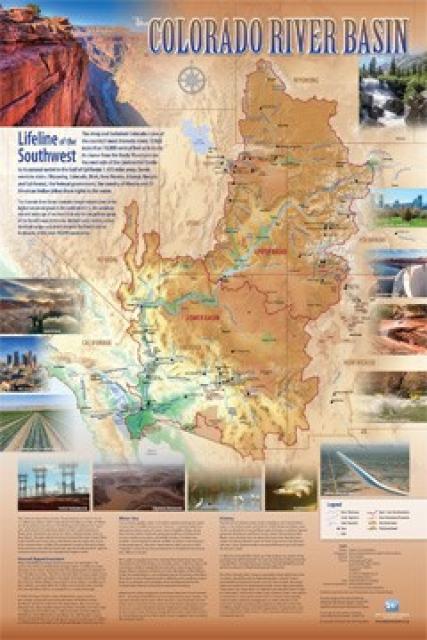

A Rancher-Led Group Is Boosting the Health of the Colorado River Near Its Headwaters

WESTERN WATER SPOTLIGHT: A Colorado partnership is engaged in a river restoration effort to aid farms and fish habitat that could serve as a model across the West

High in the headwaters of the Colorado River, around the hamlet of Kremmling, Colorado, generations of families have made ranching and farming a way of life, their hay fields and cattle sustained by the river’s flow. But as more water was pulled from the river and sent over the Continental Divide to meet the needs of Denver and other cities on the Front Range, less was left behind to meet the needs of ranchers and fish.

High in the headwaters of the Colorado River, around the hamlet of Kremmling, Colorado, generations of families have made ranching and farming a way of life, their hay fields and cattle sustained by the river’s flow. But as more water was pulled from the river and sent over the Continental Divide to meet the needs of Denver and other cities on the Front Range, less was left behind to meet the needs of ranchers and fish.

“What used to be a very large river that inundated the land has really become a trickle,” said Mely Whiting, Colorado counsel for Trout Unlimited. “We estimate that 70 percent of the flow on an annual average goes across the Continental Divide and never comes back.”

Ranchers on the river who once relied on floodwater from the Colorado River to irrigate their hayfields now must pump from the river to irrigate. The river is shallow, sandy and warm in spots. Irrigation ditches have sloughed. The stretch of the river near Kremmling has not been working well for ranchers or the environment.

Now, a partnership of state, local and conservation groups, including Trout Unlimited, is engaged in a restoration effort that could serve as a template for similar regions across the West. Centered around the high plateau near Kremmling, a town of about 1,400 people in northern Colorado about 100 miles west of Denver, the partnership aims to make the river function better for people and the environment.

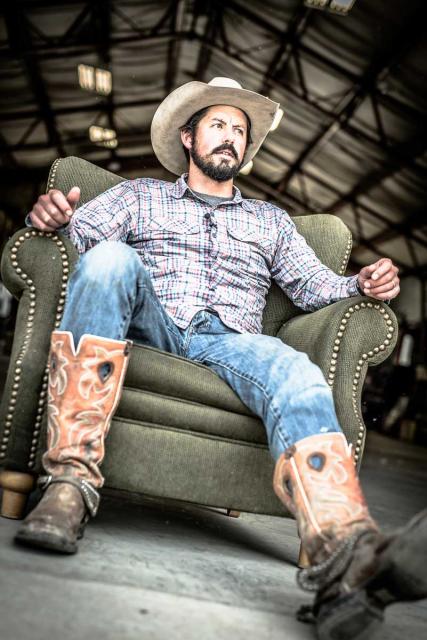

Paul Bruchez, a fifth-generation rancher of 6,000 acres near Kremmling who also runs fly fishing expeditions for tourists, sees the river’s challenges from both perspectives.

Paul Bruchez, a fifth-generation rancher of 6,000 acres near Kremmling who also runs fly fishing expeditions for tourists, sees the river’s challenges from both perspectives.

“Some of us involved with fly fishing care deeply about the environmental conditions within the river corridor,” said Bruchez. “Other landowners are more focused on the agricultural sustainability. But the one thing we agreed about is that things were collapsing.”

Restoring a Healthier River

The partnership, known as the Irrigators of the Lands in the Vicinity of Kremmling (ILVK), obtained grant funding in 2015 to start the process of assessing the river’s conditions and identifying possible pilot projects, such as stabilizing riverbanks and reviving irrigation channels across a meandering 12-mile stretch of the Colorado River. As projects are identified, ILVK members attempt to prioritize them and apply for grants with the project costs evenly divided between grantors and landowners, Bruchez said.

River improvements often have immediate benefits for irrigation infrastructure.

“Many of our irrigation laterals had washed into the river system and there was no large-scale look at the system as a whole and how it connects,” Bruchez said. “A lot of these simple bank stabilization projects not only create habitat but are literally safeguarding some of our irrigation laterals that we all rely on to deliver the water to our crops.”

The key, he said, is realizing that less can be more in re-establishing a proper flow regime. “You set the stage for the river then you let the river do the work itself instead of getting in there and manipulating everything,” he said.

Story continues below slideshow.

Trout Unlimited is a full partner in the project. It applied for all the funding and is the fiscal agent and manager of the grants. Whiting and Bruchez consult on project management, retention of consultants and scope of work.

“It’s a complete win for everybody. It’s just a question of money,” Whiting said. “It’s been so successful and such a good story and so far, we have been able to draw quite a bit of funding and turn that into impressive improvements for the river and the ranchers.”

The partnership has obtained $2.6 million in grants from funders such as the Colorado Water Conservation Board ($500,000), the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service ($2 million) and the Gates Family Foundation ($120,000).

“What used to be a very large river that inundated the land has really become a trickle.”

~Mely Whiting, Colorado counsel for Trout Unlimited

Four miles downstream from Bruchez, the Colorado River becomes a smaller river with warmer temperatures that have spurred algae growth. “The minimum stream level of the Colorado River at Kremmling is 150 cubic feet per second,” said rancher Bill Thompson. “That’s not much.”

Thompson, who ranches about 400 acres, moved to Kremmling in 1959. He said he’s spent about $200,000 to match grant funding for two grade-control projects that have raised the river channel 18 inches near his property. While helping him get the water he needs, the structures also help create fish habitat.

“I speed the water up, I’ve got them [fish] more oxygen and I’ve cooled [the water] down,” he said. “It’s a healthier river now because of it.”

River projects are undertaken to be cost-effective. “We are trying to do this in a capacity where it is more affordable,” Bruchez said. “These are not people that live on limitless budgets that are doing this for building Disneyland fish habitat. These are multigeneration ag producers that just want to be able to irrigate.”

Overcoming Skeptical Landowners

Moving water great distances helps meet Colorado’s water supply demand. The Continental Divide spans the length of the state, with watersheds on the west side flowing toward the Pacific Ocean and those on the east feeding the Atlantic Ocean. The more rural Western Slope of the Rockies gets most of Colorado’s precipitation, about 80 percent, and a vast network of storage and conveyance infrastructure moves water to major cities like Denver, Boulder and Aurora.

That diversion has come at the expense of the Colorado River in the area near Kremmling. “Where you had a very large river there is now a very small river,” Whiting with Trout Unlimited said. “It doesn’t have enough water; it is overly wide and shallow, and it gets really hot.”

Prior to the diversions, the Colorado River’s floodwaters washed over the land and helped prepare it for planting.

“You didn’t even need a water right,” said Thompson, the longtime rancher. “All you had to do was take your rake out there and scrape off the logs and the willows and start haying.”

Getting to a place where landowners agreed to commit themselves to projects took time. “It’s fair to say most landowners were pretty skeptical,” Bruchez said. “These are people that like private lives. They don’t like public dollars; they don’t like meetings and they don’t like talking about stuff. They like doing their thing.”

“When we all work together and are able to talk about the issues, we can solve problems. If we all go to our corners and put up our fists, it doesn’t work so well.”

~Paul Bruchez, fifth-generation rancher and fly fishing guide

Eventually a cost-sharing structure emerged that focused on improving the condition of the river, with grant funding helping to cover the gap beyond out-of-pocket expenses for traditional repairs. River fixes run the gamut, from rebuilding lost banks to altering the channel with rock that makes the current meander, ebb and flow. This, in turn, stimulates the production of insects that fish feast on. Bruchez said anglers tell him the results are “off the charts.”

Calming Suspicions

A restored Colorado River means good things for the ranchers near Kremmling and the trout that thrive in its waters. How much further work happens and at what scale remains to be seen, but it’s clear that the merits have been demonstrated. For her part, Whiting said the next challenge and hard conversation will entail finding ways to leave more water in the river.

Beyond the physical improvements to the river, the interaction between stakeholders has also worked well, Bruchez said, especially with trans-mountain diverters such as Denver Water. “We all view it now as a one-river thing, and when we all work together and are able to talk about the issues, we can solve problems,” he said. “If we all go to our corners and put up our fists, it doesn’t work so well.”

Whiting said partnerships between landowners and outside agencies work best when people like Bruchez are there to serve as a bridge.

Whiting said partnerships between landowners and outside agencies work best when people like Bruchez are there to serve as a bridge.

“They can go in and say, ‘These guys are not coming to take your water, they are not here to take your land,’” she said. “All these suspicions can be calmed when you have a trusted source who walks stakeholders through it.”

As 2019 moves toward 2020, more bank and river channel work is scheduled. Centered at the swirl of activity, Bruchez said he wants to keep things in perspective.

“We’ve got a lot of work to do and we are trying to not get too big for our britches,” he said. “We also recognize there are river-system challenges all over the country, especially in the Southwest, and we are hoping as a collective group that this project is enough of a success that we can really try and demonstrate to others how people can come together and accomplish a successful project, especially by reasonably affordable techniques of installation.”

How They Did It

2002-2006 Drought in Upper Colorado River Basin exacerbates irrigation challenges facing landowners near Kremmling, Colorado.2013-2014 Rancher Paul Bruchez and other landowners known as Irrigators of the Lands in the Vicinity of Kremmling (ILVK) solicit funds for an assessment of irrigation and stream restoration needs in approximately 12 miles of the Colorado River near Kremmling. The assessment is completed in 2014.

2015 The Colorado Basin Roundtable funds a pilot project to restore two riffle-pool structures on a stretch of the river. One ILVK landowner shares the cost. The project, completed in 2015, facilitated irrigation diversions and improved aquatic habitat.

2016-2019 The Colorado Water Conservation Board awards a $465,400 grant for improvement projects. ILVK landowners commit to match that with another $465,400. Construction is ongoing.

2016-Present USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service awards Trout Unlimited $7.75 million for the Colorado River Headwaters Project. About $2 million is dedicated for projects benefitting the ILVK region, including channel and habitat projects to improve irrigation systems as well as soil and water quality through the ILVK river reach.

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.