Researchers Aim to Give Homeless a Voice in Southern California Watershed

NOTEBOOK: Assessment of homeless water challenges part of UC Irvine study of community water needs

A new study could help water

agencies find solutions to the vexing challenges the homeless

face in gaining access to clean water for drinking and

sanitation.

A new study could help water

agencies find solutions to the vexing challenges the homeless

face in gaining access to clean water for drinking and

sanitation.

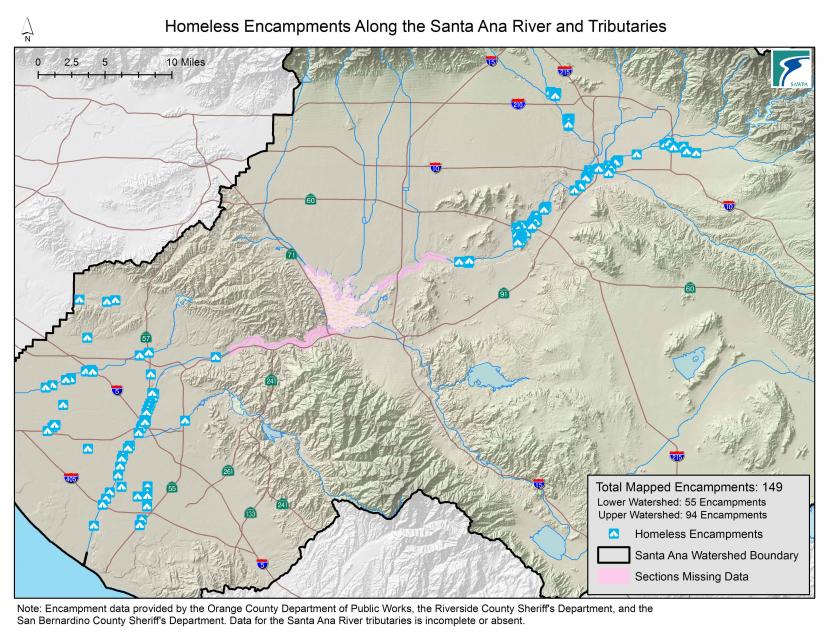

The Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority (SAWPA) in Southern California has embarked on a comprehensive and collaborative effort aimed at assessing strengths and needs as it relates to water services for people (including the homeless) within its 2,840 square-mile area that extends from the San Bernardino Mountains to the Orange County coast.

The effort also focuses on disadvantaged communities, which the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) defines as those with a median household income of less than 80 percent of the statewide average. Estimates are that 28 percent of the 6 million residents of the SAWPA watershed fall into that category.

SAWPA has enlisted the services of anthropologists with the University of California, Irvine, as part of a team that embarked this year on a three-year study of how water is thought of, used and conserved by people living and working within its boundaries.

“We are using an ethnographically

informed approach … that looks at culture and gathers things

like local knowledge, daily experiences and the explanatory model

that people use in their everyday lives,” said Emily Brooks, a

postdoctoral scholar in anthropology at UC Irvine. She said

the study is one of the first of its kind in California.

“We are using an ethnographically

informed approach … that looks at culture and gathers things

like local knowledge, daily experiences and the explanatory model

that people use in their everyday lives,” said Emily Brooks, a

postdoctoral scholar in anthropology at UC Irvine. She said

the study is one of the first of its kind in California.

Brooks said she and others are conducting interviews and listening sessions to identify trends and “compare them between and across communities.” The range of communities they’ll be talking with goes from middle class suburban households to low income and homeless people who often get overlooked.

“People in their wisdom and expertise have decided that just telling communities what they need is not necessarily working, so the idea is to change that flow.”

~ UC Irvine researcher Valerie Olson

Lead researcher Valerie Olson with UC Irvine said “one of the virtues of this project is that it’s being conducted, because there is a concern about the directionality of the information” between water agencies and the people they serve.

“People in their wisdom and expertise have decided that just telling communities what they need is not necessarily working, so the idea is to change that flow,” she said. “Instead of doing outreach and diagnostic approaches where experts diagnose problems in communities, the idea is to … flow it the other way and do ‘inreach’ – how do we understand what people are thinking and do it in a way, through narratives, that allows for the full explanation of water experiences to come through or community strengths as well as needs in order to create a larger context for thinking about problem-solving.”

Analyzing the needs of disadvantaged

communities is not a new phenomenon at SAWPA, where “extensive

work” has been done on environmental justice issues and goals to

support low-income communities, said Mike Antos, SAWPA’s senior

watershed manager.

Analyzing the needs of disadvantaged

communities is not a new phenomenon at SAWPA, where “extensive

work” has been done on environmental justice issues and goals to

support low-income communities, said Mike Antos, SAWPA’s senior

watershed manager.

But the focus on homelessness pushes the investigation into a new realm, he said, noting “there are vastly more intersections between homelessness and water management than most people think about.

“Most people in the water sector say it’s all about how encampments are a source of pollution and that’s where they start and stop thinking about homelessness,” he said. “The homeless advocates on the other side think about the lack of access to drinking water and a lack of access to sanitation.”

Under Proposition 1, the water infrastructure bond approved by voters in 2014, 10 percent of the statewide funding for the Integrated Regional Water Management Program must be directed to the Disadvantaged Communities Involvement Program. Within SAWPA, that amounts to about $6.3 million for the program. The goal is to ensure that members of disadvantaged communities, economically distressed areas and underrepresented communities are able to participate in the planning process.

The idea of including people who

often get overlooked, such as the homeless, has drawn attention,

Antos said.

The idea of including people who

often get overlooked, such as the homeless, has drawn attention,

Antos said.

“The idea has spread,” he said. “Other regions that are implementing the Disadvantaged Communities Involvement Program have adopted this focus on homelessness. Ventura, greater Los Angeles County and the Bay Area have decided it’s important and they are exploring the relationship between homelessness and water.”

Craig Cross, manager of DWR’s Disadvantaged Communities Involvement Program, agreed that the relationship between homelessness and water is emerging as a focus in the state’s urban areas, though state grant funding has limitations.

“Unfortunately, the money is strictly for water management,” he said. “The lens that it has to be looked through is water management.” And the focus must remain with water management, “because homelessness has a lot of other issues – mental health, addiction and housing in California, in general.”

“Most people in the water sector say it’s all about how encampments are a source of pollution and that’s where they start and stop thinking about homelessness.”

~ Mike Antos, SAWPA senior watershed manager

A goal of the UC Irvine study, Antos said, is to help water agencies contribute to improving the lives of the people who are the focus of the Disadvantaged Communities Involvement Program, including the homeless. SAWPA has identified flood protection, water quality, sanitation/health, riparian and recreational areas and the Human Right to Water as the issues for which innovative solutions for the homeless are needed.

California’s Human Right to Water Law, which became effective in 2013, states every human being has the “right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes.”

SAWPA staff notes that “additional work is needed at all levels of government as this … law becomes policy, and practice throughout the state,” and that homelessness “presents significant challenges to enacting this policy.”

Antos said he expects SAWPA’s work

will strengthen how water agencies move into the

collaborative realm of addressing the issue of homelessness.

Antos said he expects SAWPA’s work

will strengthen how water agencies move into the

collaborative realm of addressing the issue of homelessness.

“Our easiest win would be for all of us water sector folks to join up as partners in this effort,” he said. “Not seeking to be in charge or to lead, not claiming responsibility for the whole problem, but recognizing that we have a part to play and that a comprehensive solution is one that will benefit our missions too.”