A Study of Microplastics in San Francisco Bay Could Help Cleanup Strategies Elsewhere

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: Debris from plastics and tires is showing up in Bay waters; state drafting microplastics plan for drinking water

Blasted by sun and beaten by waves,

plastic bottles and bags shed fibers and tiny flecks of

microplastic debris that litter the San Francisco Bay where they

can choke the marine life that inadvertently consumes it.

Blasted by sun and beaten by waves,

plastic bottles and bags shed fibers and tiny flecks of

microplastic debris that litter the San Francisco Bay where they

can choke the marine life that inadvertently consumes it.

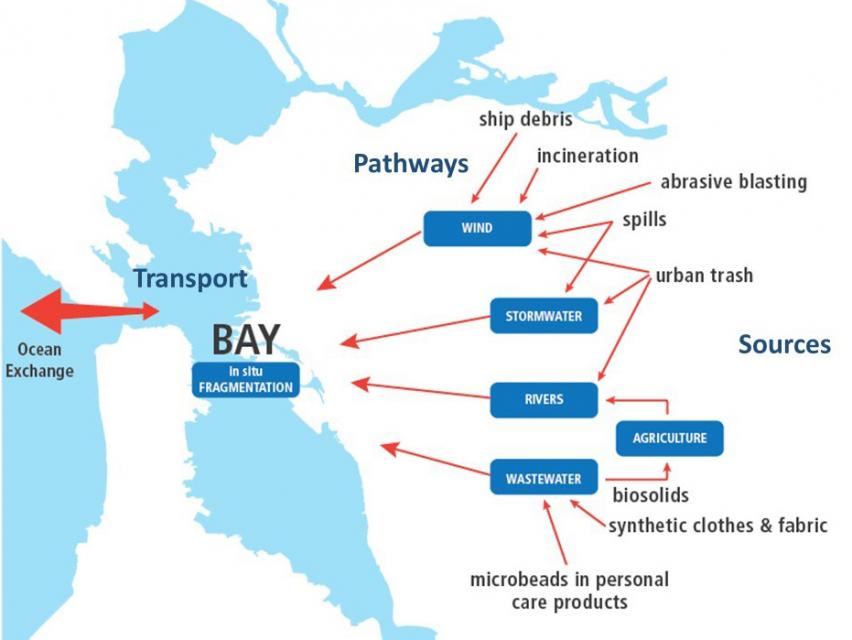

A collaborative effort of the San Francisco Estuary Institute, The 5 Gyre Institute, San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board and the regulated discharger community that aims to better understand the problem and assess how to manage it in the San Francisco Bay is nearing the end of a three-year study.

The conclusions and recommendations, while focused on the San Francisco Bay, could help other regions make similar assessments of microplastic pollution, said Diana Lin, an environmental scientist with the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) who is among the researchers working on the report. She spoke July 2 at the California Water Data Science Symposium in Sacramento.

“Our work is definitely intended for a wider audience,” Lin said. “Our field study design is focused on San Francisco Bay, but the results should be useful for evaluating other regions, and our recommendations will apply broadly.”

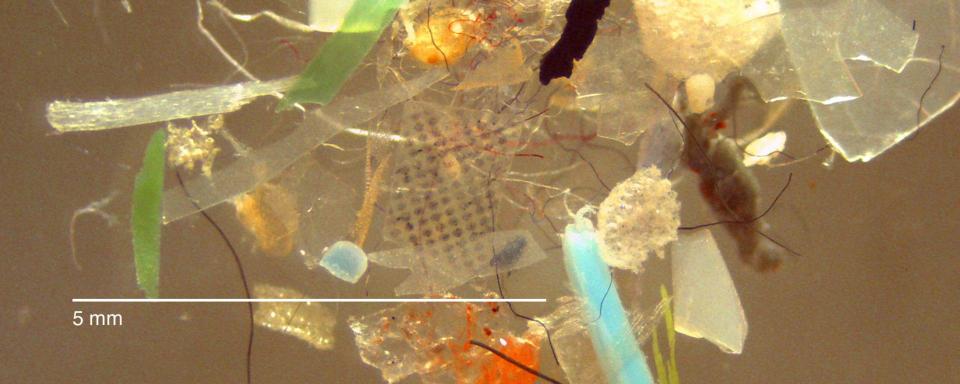

Plastics are a part of everyday consumer products, from toothpaste to clothing to food and beverage containers. When they break down into smaller pieces, the tiny (less than 5 millimeters, or smaller than the size of a sesame seed) bits of debris can wash ashore or be accidentally consumed by birds, fish or marine mammals. They may also be showing up in things people consume – particularly drinking water.

Scientists, water quality experts

and lawmakers are learning more about what microplastics are, the

extent of contamination and how to keep them out of the

environment. California aims to have the beginnings of a control

plan in place by 2021.

Scientists, water quality experts

and lawmakers are learning more about what microplastics are, the

extent of contamination and how to keep them out of the

environment. California aims to have the beginnings of a control

plan in place by 2021.

“Microplastics are being detected everywhere and the public is concerned, prompting action at the local, federal and state levels,” Lin said.

SFEI’s findings are expected to guide solutions, including where the best intervention points are. The study will explain the types of microplastics being found and their sources. The particles are identified as fragments, fiber, pellet, film and foam.

In addition to the harm caused to marine life, microplastics could be vectors for harmful bacteria. “We don’t yet know the ecological effects,” said Lin. “Once it’s in the environment, we can’t just pick it up.”

SFEI’s monitoring has looked at bay versus ocean conditions and wet versus dry season. Microplastics are measured at a maximum rate of 1 million particles per square kilometer and the evaluation process is challenging, with each sample taking 30 hours to analyze, Lin said.

The process differs based on the

techniques used and the number of particles in the sample. “Each

particle is individually and manually picked out of the sample,

and labeled on double-sided tape with an identification,” Lin

said. “Each particle is recorded for color, morphology,

measurement, and then it takes 15 minutes per particle to run

through [analysis] for plastic confirmation.”

The process differs based on the

techniques used and the number of particles in the sample. “Each

particle is individually and manually picked out of the sample,

and labeled on double-sided tape with an identification,” Lin

said. “Each particle is recorded for color, morphology,

measurement, and then it takes 15 minutes per particle to run

through [analysis] for plastic confirmation.”

The study team sampled both the wastewater treated at sewage treatment plants and the stormwater that rolls off hard surfaces, carrying urban runoff into storm drains. “Microplastics are really abundant in stormwater, with lots of rubbery fragments likely from tires,” she said. The stormwater concentrations were much higher than wastewater detections. Microplastics contamination can be very sporadic and work is continuing to figure out background levels, Lin said.

Microplastics in Drinking Water

Plastics are essentially indestructible. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, about 80 percent of marine debris comes from land-based sources, with food and beverage packaging making up the largest component.

In the home, when synthetic clothes are washed, microfibers are released from the washing machine. The microfibers travel to local wastewater treatment plants, where as much as 40 percent of the microfibers can enter waterways. Removing microfibers at the wastewater treatment level would be “prohibitively expensive,” Lin said.

People are ingesting microplastics

as well. In 2018, researchers at the State University of New York

and the University of Minnesota tested 159 drinking water samples

worldwide and found 83 percent of the samples contained

microplastics.

People are ingesting microplastics

as well. In 2018, researchers at the State University of New York

and the University of Minnesota tested 159 drinking water samples

worldwide and found 83 percent of the samples contained

microplastics.

How microplastics affect human health is an unresolved issue. A June 2019 study by the University of Victoria in Canada estimated that annual microplastics consumption by people ranges from 39,000 to 52,000 particles, with the numbers increasing to between 74,000 and 121,000 particles when inhalation is considered. People who drink bottled water exclusively may be ingesting an additional 90,000 microplastics particles annually, compared to 4,000 microplastics particles for those who consume only tap water, the study said.

“Microplastics are really abundant in stormwater, with lots of rubber fragments from tires.”

Diana Lin, an environmental scientist with the San Francisco Estuary Institute

“Our research suggests microplastics will continue to be found in the majority — if not all — of items intended for human consumption,” Kieran Cox, lead author of the study, said in a press release by the University of Victoria in Canada. “We need to reassess our reliance on synthetic materials and alter how we manage them to change our relationship with plastics.”

Plant-based plastics and natural materials such as cotton and hemp have been touted as alternatives to petroleum-based plastics for containers and clothing. Coca-Cola, for example, is bottling products using a recyclable PET plastic bottle made partially from plant waste. But studies suggest not all so-called bioplastics harmlessly decompose, and cultivating crops for fiber or bioplastics can have their own impacts on the environment.

A State Microplastics Strategy

California lawmakers in 2018 passed a package of bills to help increase the knowledge of the risks of microplastics and microfibers on the marine environment and in drinking water.

The first law requires the State Water Resources Control Board to adopt a definition of microplastics in drinking water and a standard testing method by July 2020. That law was followed by plans for a microplastics strategy that require state agencies to investigate the problem and submit the strategy to the state Legislature by the end of 2021. A progress report along with recommendations for policy changes or additional research is required by the end of 2025.

“It is crucial that the public be made aware of the extent of microplastics in the drinking water we consume daily,” Sen. Anthony Portantino, D-La Cañada Flintridge, who authored the bills, said in an October 2018 statement. “Greater knowledge of the contaminants in drinking water can lead to increased efforts of recycling, decreased use of plastics, decreased pollution, and overall a healthier public and planet.”

Wastewater treatment agencies are

aware of the microplastics problem. The San Francisco Public Utilities

Commission considers them a constituent of emerging concern

and is looking to better understand the role of wastewater

treatment plants in managing microplastics, Will Reisman, press

secretary with the PUC, wrote in an email to Western

Water.

Wastewater treatment agencies are

aware of the microplastics problem. The San Francisco Public Utilities

Commission considers them a constituent of emerging concern

and is looking to better understand the role of wastewater

treatment plants in managing microplastics, Will Reisman, press

secretary with the PUC, wrote in an email to Western

Water.

“Wastewater treatment plants are designed to remove trash and debris, like single-use plastic items, and recent research shows that existing wastewater treatment processes may remove some microplastics,” Reisman wrote. “Additional preliminary research shows microplastic removal [can be done] through green infrastructure, such as rain gardens and bioswales, which capture plastic before it enters our storm drains.”

The PUC does not expect to upgrade or retrofit its facilities to further treat for microplastics, nor does it expect state regulations requiring them to do so, according to Reisman. Instead, the plan is to address microplastics at the source through outreach, education and engagement with industry and the public, rather than waiting for the pollutant to reach the treatment plants downstream.

Still, Reisman wrote, “We would welcome conversations with our regulators and producers of plastics on how to best reduce microplastics in our environments and improve water quality in the San Francisco Estuary and Pacific Ocean.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.