Testing at the Source: California Readies a Groundbreaking Hunt to Check for Microplastics in Drinking Water

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: Regulators and water systems are finalizing a first-of-its-kind pilot that will determine whether microplastics are contaminating water destined for the tap

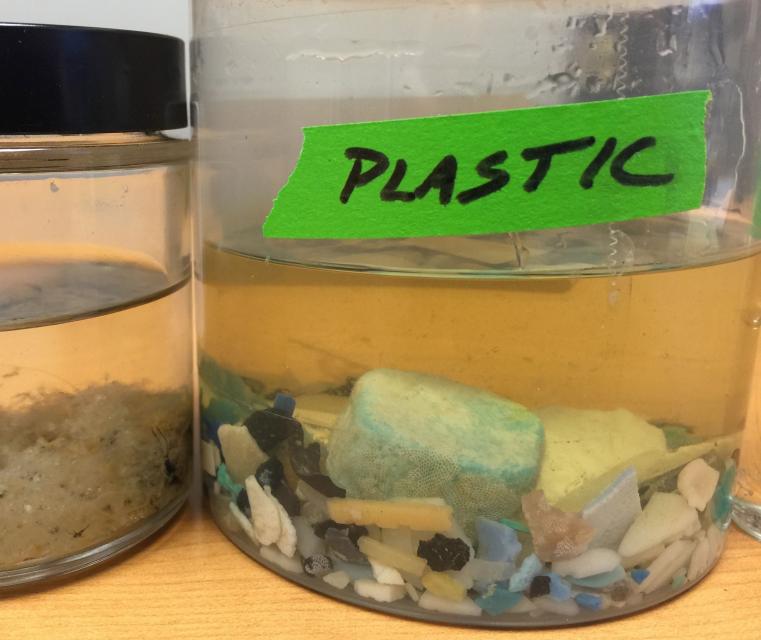

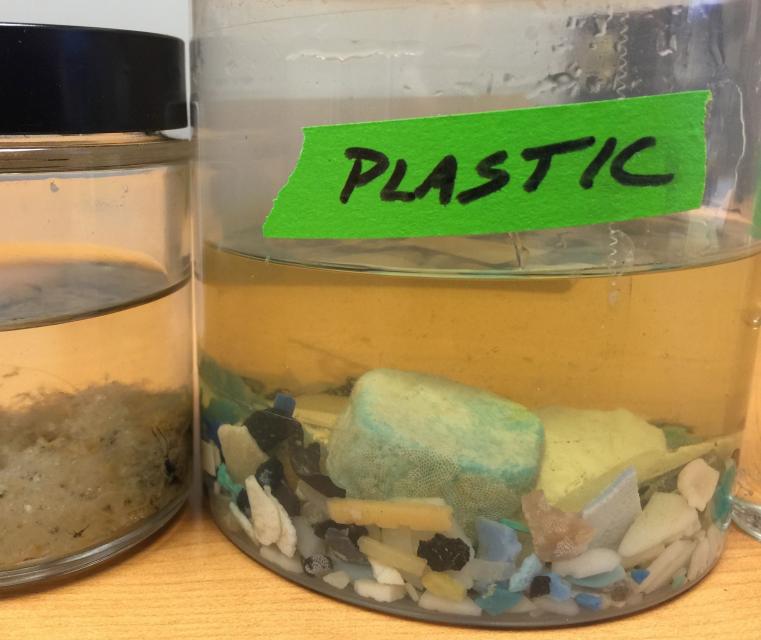

Tiny pieces of plastic waste shed

from food wrappers, grocery bags, clothing, cigarette butts,

tires and paint are invading the environment and every facet of

daily life. Researchers know the plastic particles have even made

it into municipal water supplies, but very little data exists

about the scope of microplastic contamination in drinking

water.

Tiny pieces of plastic waste shed

from food wrappers, grocery bags, clothing, cigarette butts,

tires and paint are invading the environment and every facet of

daily life. Researchers know the plastic particles have even made

it into municipal water supplies, but very little data exists

about the scope of microplastic contamination in drinking

water.

After years of planning, California this year is embarking on a first-of-its-kind data-gathering mission to illuminate how prevalent microplastics are in the state’s largest drinking water sources and help regulators determine whether they are a public health threat.

The State Water Resources Control Board has approved standardized testing methods and is courting laboratories to process samples before the world’s first microplastics monitoring program begins in late 2023. Meanwhile major water agencies tapped for the first round of testing are gathering resources, figuring out how to take samples and readying public messaging strategies in case microplastics turn up in streams and reservoirs.

“No regulating authority has done a monitoring program before, so it’s groundbreaking,” said Paul Rochelle, water quality manager for Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. “The state is on a journey and we’re on that journey along with other California water agencies.”

California Acts First

Plastic pollution has been mounting globally for decades but it’s no longer an abstract threat floating in the oceans and gathering on secluded beaches. Small bits of plastic debris are coating mountain snowpacks, contaminating indoor air quality and littering drinking water sources.

“If your water source is a reservoir or a river, which is the case for a decent amount of the United States, then there’s a high likelihood that there is some microplastic in it.”

~Scott Coffin, research scientist, State Water Resources Control Board

Microplastics – plastic debris measuring less than 5 millimeters, or about the size of a sesame seed – enter the environment as industrial microbeads or as larger plastic litter that degrade into small pellets. Most microplastics can take thousands of years to naturally biodegrade and some of the tiny particles can escape traditional wastewater treatment systems before ending up in oceans or freshwater waterways. The main sources of microplastics in freshwater come from commonly used items: single-use food packaging, clothing, tires, paints, cigarette butts and personal care products.

Researchers have confirmed that humans are ingesting microplastics in both bottled and tap water. A 2017 analysis by Orb Media, a Washington D.C. based nonprofit journalism organization, examined tap water from across the globe and found the microscopic plastic fibers in 83 percent of the samples.

“If your water source is a reservoir or a river, which is the case for a decent amount of the United States, then there’s a high likelihood that there is some microplastic in it,” said Scott Coffin, research scientist at California’s State Water Board.

The California Legislature, prompted by the troubling scientific evidence, in 2018 passed Senate Bill 1422, which required the State Water Board to develop microplastics testing methods for municipal water systems. A companion bill also required the state to implement a statewide strategy to reduce marine plastic pollution.

As part of SB 1422, the State Water Board in 2020 adopted a microplastics in drinking water definition and in 2022 it approved the world’s first policy handbook for testing water supplies for microplastics.

Testing at the Source

Approximately 30 of California’s largest water systems will have to submit quarterly tests for two years, beginning sometime this fall or winter. The State Water Board is still finalizing the list, but it will include an assortment of major urban systems that provide water to residents of cities like Los Angeles, Fresno, San Francisco and Sacramento.

According to the State Water Board’s

Coffin, who led the international working group that developed

California’s testing strategy and has been studying microplastics

since 2014, California’s primary concern isn’t with groundwater

supplies but surface water. For the first half of the four-year

program, test samples will come directly from untreated surface

water sources, potentially sites like the Sacramento River, Hetch

Hetchy Reservoir in Yosemite National Park that provides drinking

water to San Francisco or Metropolitan’s Diamond Valley Lake, a

water storage reservoir that supplies much of Southern

California.

According to the State Water Board’s

Coffin, who led the international working group that developed

California’s testing strategy and has been studying microplastics

since 2014, California’s primary concern isn’t with groundwater

supplies but surface water. For the first half of the four-year

program, test samples will come directly from untreated surface

water sources, potentially sites like the Sacramento River, Hetch

Hetchy Reservoir in Yosemite National Park that provides drinking

water to San Francisco or Metropolitan’s Diamond Valley Lake, a

water storage reservoir that supplies much of Southern

California.

Coffin said testing source water first is necessary because most water treatment plants are already removing particles down to such a low amount that current testing techniques can’t reliably identify the smallest plastic fibers that can escape the water treatment process. If the testing technology evolves to accurately detect the smallest of plastic particles — something Coffin expects to happen — the second phase of the testing program will extend to treated drinking water.

Results from the tests, which are expected to cost around $2,000 per sample, will be listed on the State Water Board’s website and in some water systems’ Consumer Confidence Reports.

In addition to crafting the testing program, Coffin and the State Water Board have been convening workshops and studies to better understand the health effects of microplastics. Coffin said there is growing research showing that ingesting microplastics can cause inflammation and oxidative stress to humans, and unlike some chemicals, microplastics don’t target certain organs or systems.

“They pretty much just hurt any cell they come in contact with,” said Coffin.

Unique Challenges

California’s microplastics mandate is presenting a variety of hurdles for water agencies that are trying to adopt the unique system.

Lesley Dobalian, chair of the Association of California Water Agencies (ACWA) microplastics in drinking water work group, said water agencies are training employees, scrambling to draft testing protocols and figuring out how to pay for the new requirements.

“There are challenges that are unique to this type of monitoring,” said Dobalian, who is also a principal water resources specialist for the San Diego County Water Authority.

“If microplastics are detected in source water, that doesn’t mean microplastics are present in the treated water that is actually delivered to our homes.”

~Lesley Dobalian, chair, Association of California Water Agencies microplastics work group

A particular concern for water agencies is figuring out how to accurately gather samples, as the risk of background contamination with microplastics is higher than for other constituents that are currently tested, said Metropolitan’s Rochelle. Standard labs are filled with items that contain plastic from instruments, carpets, wall coverings to employees’ clothes.

“It’s very important to do all of the quality assurance and quality controls and run lots of sampling and analysis blanks to make sure that if we do find microplastics, we know they’re actually coming from the water we sampled,” said Rochelle.

Metropolitan, which has 26 member agencies that serve 19 million people across six Southern California counties, has repurposed a room at its water quality lab specifically to handle microplastics and it will apply for accreditation with the state to analyze its own samples. Rochelle said Metropolitan has been budgeting for several years to accommodate the new monitoring load.

“Although it is additional work, I wouldn’t classify it as a burden because this is what we’re here for. This is part of water quality’s reason to exist, to prepare for and respond to emerging issues as they come up,” he said.

Others are not as far along in their planning and contend they need more guidance from the State Water Board.

The city of Fresno, which gets its surface water supply from the San Joaquin and Kings rivers, said it doesn’t know if it will be required to test groundwater, surface water or treated water.

“We are awaiting direction on how testing will be conducted,” Sontaya Rose, the city’s director of communications, wrote in an email. “Without knowing the specific protocol, it’s hard to anticipate challenges.”

If microplastics are found in the

city’s water, Rose added, it most likely would be in its surface

water sources.

If microplastics are found in the

city’s water, Rose added, it most likely would be in its surface

water sources.

Coffin, the State Water Board’s microplastics specialist, countered that the monitoring guidelines are spelled out in the handbook released last year and added that the State Water Board will be providing guidance and training for water agencies on test sampling protocols this summer.

Dobalian, with ACWA’s microplastics committee, said water agencies must be ready to accurately explain what the results of the first round of testing actually mean and reassure the public that tap water is safe.

“If microplastics are detected in source water, that doesn’t mean microplastics are present in the treated water that is actually delivered to our homes,” she said.

Coffin echoed the need for clear communication and noted that many common water treatment methods, including reverse osmosis and microfiltration, remove microplastics at a high rate. He said the last thing the State Water Board wants is for residents to turn to bottled water, which creates more plastic pollution and contains up to three times higher concentrations of microplastic than tap water.

Coffin cast the testing program as an opportunity for water agencies to craft carefully considered messaging campaigns and ultimately win trust from their customers.

“They can say ‘we are monitoring for something no one else in the world is and that’s because we care about your health and we’re being transparent about it,’” said Coffin.

On The Cusp

California and its water agencies are on the verge of creating a unique dataset that will verify whether its streams, reservoirs and tap water are polluted with tiny fragments of plastic and synthetic fibers such as polyester used in clothing. The information may also help epidemiologists determine if certain illnesses or diseases are occurring at a higher rate in areas that have microplastic in their water. Coffin worked on a 2022 study that found ingesting microplastics may harm the male reproductive system.

The testing program could also

lay a foundation for California to take another pioneering

step and set an enforceable threshold for microplastics in

drinking water.

The testing program could also

lay a foundation for California to take another pioneering

step and set an enforceable threshold for microplastics in

drinking water.

Nearly five years after the passage of SB 1422, California remains the only state with a mandate to test for microplastics in drinking water. Others are paying attention though as the New Jersey Legislature has proposed a similar program and the New York City Council is considering routine testing for microplastics in the city’s tap water.

“California is clearly leading the way on this globally,” Coffin said, “and it’s caused so much research, innovation and widespread collaboration that it really has prompted progress in the [microplastics] field.”

Reach Writer Nick Cahill at ncahill@watereducation.org, and Editor Doug Beeman at dbeeman@watereducation.org.

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook , Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.