Understanding Streamflow Is Vital to Water Management in California, But Gaps In Data Exist

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: A new law aims to reactivate dormant stream gauges to aid in flood protection, water forecasting

California is chock full of rivers and creeks, yet the state’s network of stream gauges has significant gaps that limit real-time tracking of how much water is flowing downstream, information that is vital for flood protection, forecasting water supplies and knowing what the future might bring.

California is chock full of rivers and creeks, yet the state’s network of stream gauges has significant gaps that limit real-time tracking of how much water is flowing downstream, information that is vital for flood protection, forecasting water supplies and knowing what the future might bring.

That network of stream gauges got a big boost Sept. 30 with the signing of SB 19. Authored by Sen. Bill Dodd (D-Napa), the law requires the state to develop a stream gauge deployment plan, focusing on reactivating existing gauges that have been offline for lack of funding and other reasons. Nearly half of California’s stream gauges are dormant.

“Stream gauges provide important information in this era of droughts and flooding, driven in part by climate change,” Dodd said in a statement after the bill’s signing. “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.”

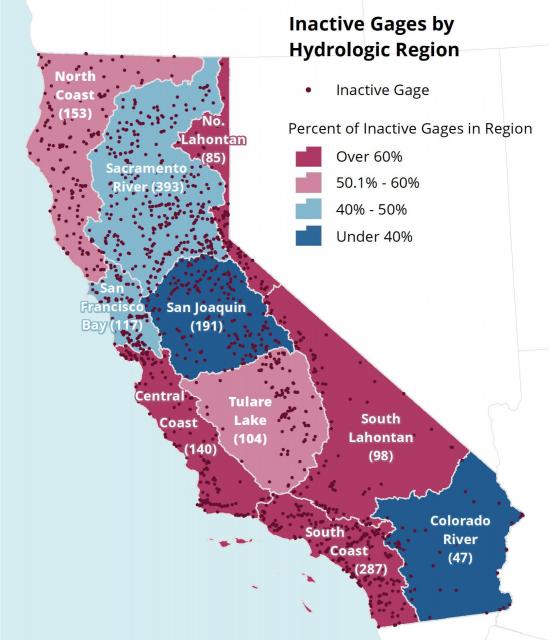

Gauges measure and relay information about streamflow and other data, but as currently deployed they give an incomplete picture of what’s happening on rivers and streams. Some provide data in real time, but many others do not and may even require regular monitoring. According to The Nature Conservancy, which sponsored the bill, stream gauges have been active at some point at more than 3,600 locations across California, but only 54 percent have been active recently.

Stream gauges “are crucial for all sorts of activities in terms of water supplies, safety and ecological concerns. They enable us to understand the water budget.”

~Eric Reichard, director of the U.S. Geological Survey’s California Water Science Center

David Guy, president of the Northern California Water Association, which supported the bill, called the signing of SB 19 a big deal despite the relative lack of news coverage. There’s been a lot of discussion about the need for more precise data on things such as river flows, Guy said, and improving the stream gauge network is an important piece of that. “It’s one of those subtle, small things that is a lot bigger than people think,” he said.

Stream gauges can be found throughout the state, operated by an array of local, state and federal agencies such as the U.S. Geological Survey. While a large quantity of data is available about gauges in California, “That data is challenging to harmonize and analyze if one wants a complete survey of California’s gauge network,” according to the conservancy.

Stream gauges can be found throughout the state, operated by an array of local, state and federal agencies such as the U.S. Geological Survey. While a large quantity of data is available about gauges in California, “That data is challenging to harmonize and analyze if one wants a complete survey of California’s gauge network,” according to the conservancy.

“We would do better managing a very precious and fragile resource if we have more information about it,” said Jay Ziegler, California policy director with The Nature Conservancy. “That helps whether I am an advocate for adequate flows for salmon or whether (a water district like) the Metropolitan Water District wants to have better assurances of what stream conditions are.”

Furthermore, improved flow data can help local and state agencies better understand water conditions during longer periods.

“When a gauge goes offline, we lose not only the current data, but also the ability to compare current trends to historical data points from the same site,” said a report by the conservancy titled “Gage Gap.” “That historical data is a key need as climate extremes become more frequent and damaging.”

GAUGE VS GAGE: Read why some spell it differently

Kasey Schimke, legislative director with the California Department of Water Resources, said the law takes a holistic approach at where data gathering points are missing, which gaps should get filled first and with what type of information. Improved stream gauge data “helps us verify our estimates about snowpack … and validates the science of it,” he said, adding that it’s also used during flood season to understand the pulses from the various Sierra Nevada watersheds.

Water supply agencies backed the bill as a way to strengthen water management during times of tight allocations and system volatility.

“I think it informs decision-making at all levels,” said Kathy Viatella, executive legislative representative with Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. “It’s really hard to manage the system for the multiple benefits that people are focused on when you don’t have adequate information.”

Defining Where Gaps Exist

Stream gauges gather important metrics such as flow (described as cubic feet per second) and temperature. That information is used to allocate water during drought, predict floods, ensure the protection of fish and to track illegal diversions.

Stream gauges gather important metrics such as flow (described as cubic feet per second) and temperature. That information is used to allocate water during drought, predict floods, ensure the protection of fish and to track illegal diversions.

“They are crucial for all sorts of activities in terms of water supplies, safety and ecological concerns,” said Eric Reichard, director of the U.S. Geological Survey’s California Water Science Center. “They enable us to understand the water budget.”

USGS operates about 500 stream gauges in California, some of which are more than 100 years old, Reichard said. The federal agency’s gauging network has been relatively constant for the past decade. But over the longer historical period gauges have gone out of service, in some cases intentionally and sometimes because funding expired, he said.

The lack of reporting gauges is not inconsequential. According to the conservancy’s “Gage Gap” report, the 2017 crisis at the Oroville spillway highlighted a “surprising gap” in the available reporting data from the gauge network below Oroville Dam. In the Bay Area, the report said, additional gauges and more real-time reporting would have provided more notification to people living near San Jose’s Coyote Creek, which flooded in 2017.

Gauges that instantly provide a breadth of real-time data average $25,000 to install and $15,000-$20,000 per year to maintain. Such gauges are often referred to as “gold-standard gauges,” the conservancy’s “Gage Gap” report said, noting that much of the cost in such a gauge is not in the hardware but in the expertise to manage and adjust both hardware and raw data to account for the highly changeable conditions in surface water.

Wanted: An Adequate System

A robust stream gauge network is crucial toward protecting people from flooding and having superior knowledge of water resources. The signing of SB 19 was the first step in a lengthy process that involves filling in data gaps and allocating money to build and possibly expand a stream gauge network.

Though work on implementing the law has just begun, Ziegler said it’s possible some of the data gaps will be filled as soon as next year. Ideally, he said, attention is first directed at gauges that were deactivated in the last five to 10 years.

Though work on implementing the law has just begun, Ziegler said it’s possible some of the data gaps will be filled as soon as next year. Ideally, he said, attention is first directed at gauges that were deactivated in the last five to 10 years.

The next steps for the law involve carving out the funding to fulfill its ambitions, a process that begins in early 2020 as budgetary priorities are set. Ziegler said the short-term estimate is that reactivating gauges in California would cost about $15 million to $20 million.

With demands growing to quantify the multiuse benefits of water management practices, including compliance with the state’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, stakeholders believe measures such as SB 19 are key parts of the toolbox.

“Having functioning stream gauges allows the state to determine how much water is available for diversion and helps address the questions of any potential unlawful diversions,” said Viatella with Metropolitan. “It can help them determine in a wet year how much excess water could be used to do flood capture and put that water into the ground.”

Right now, she said. “We don’t have an adequate system in place.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Gauge vs Gage

According to most dictionaries, gauge is spelled with a “u”. The U.S. Geological Survey spells it without one, and therein lies a story.In the late 1800s, USGS employee Frederick Newell devised techniques for measuring streamflow that the USGS still uses today. He also is reputed to be the person responsible for USGS’ spelling of gage. According to a USGS history, “Newell reasoned that “gage” was the proper Saxon spelling before the Norman influence added a ‘u’.” He also may have been influenced by an early dictionary’s spelling of the word.

The Associated Press Stylebook, which is our style guide, retains the “u” in gauge, thus the spelling you see in this story.