When Water Worries Often Pit Farms vs. Fish, a Sacramento Valley Farm Is Trying To Address The Needs Of Both

WESTERN WATER SPOTLIGHT: River Garden Farms is piloting projects that could add habitat and food to aid Sacramento River salmon

Farmers in the Central Valley are broiling about California’s plan to increase flows in the Sacramento and San Joaquin river systems to help struggling salmon runs avoid extinction. But in one corner of the fertile breadbasket, River Garden Farms is taking part in some extraordinary efforts to provide the embattled fish with refuge from predators and enough food to eat.

Farmers in the Central Valley are broiling about California’s plan to increase flows in the Sacramento and San Joaquin river systems to help struggling salmon runs avoid extinction. But in one corner of the fertile breadbasket, River Garden Farms is taking part in some extraordinary efforts to provide the embattled fish with refuge from predators and enough food to eat.

And while there is no direct benefit to one farm’s voluntary actions, the belief is what’s good for the fish is good for the farmers.

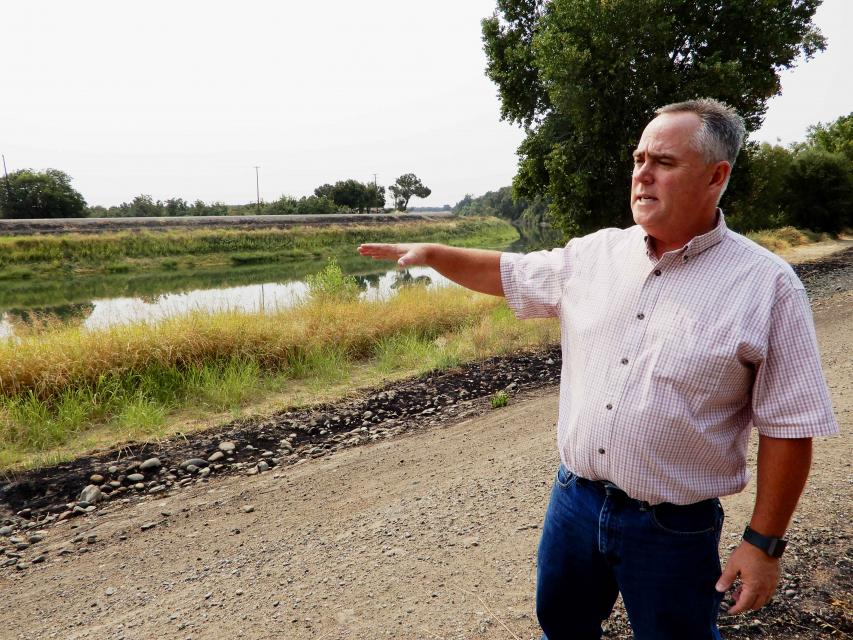

“How well [salmon] do is how well the rest of us do with our water supply,” said Roger Cornwell, general manager of River Garden Farms in Knights Landing, about 30 miles north of Sacramento. “Water is a fundamental business asset … and we’re going to be investing in our water.”

River Garden, which grows rice, walnuts, sunflowers and other crops on about 15,000 acres, is pursuing two multiyear efforts designed to aid salmon, particularly the endangered winter-run Chinook. If the science proves out – and researchers from the University of California, Davis are gathering data – then the experiments may offer a model throughout the Sacramento River region and beyond for sustaining salmon.

“How well [salmon] do is how well the rest of us do with our water supply.”

~Roger Cornwell, general manager of River Garden Farms

The fish face an arduous journey from where they hatch in the northern Sacramento Valley (via hatchery and in the wild) to the ocean where they spend about four years before returning to the river to spawn. In many places, the river has been scrubbed, stripped bare and riprapped for flood management, allowing the water to move through but leaving the fish with essentially a desert environment underwater.

Enter River Garden. Last year, they invested $400,000 (the Bureau of Reclamation contributed $200,000) in an ambitious operation to re-establish refuge spots for juvenile salmon along a quarter-mile stretch of the Sacramento River in Redding, more than 100 miles from their farm. In an impressive engineering feat, giant boulders, some with walnut tree stumps bolted to them and others with almond canopies, were lowered into the river at key locations at a bridge crossing.

River Garden Farms has taken the lead on two multi-year experiments to aid imperiled salmon in the Sacramento River: Refuge structures have been planted in the Sacramento River in Redding to help shelter juvenile salmon; and rice fields are flooded and flushed several times over the fall and winter to foster growth of microorganisms to feed fish.

Learn more: Roger Cornwell with River Garden Farms will discuss their Salmon Habitat Restoration Project during a stop on our Northern California Tour Oct. 10-12. Here’s where you can learn more about the tour and sign up.

The structures are designed to improve upon a barren river bottom where young fish have little if any way of evading hungry predators or taking a break from the pulsating current.

Everyone following the plight of salmon survival in the river is eagerly watching the three-year experiment to confirm its utility and see if it can be the catalyst for similar ventures. Sonar imagery has confirmed juvenile fish are using the artificial refuge, but more monitoring needs to be done.

“The creation of cover by planting and anchoring root wads is fundamentally a good idea, but monitoring is needed to see how the juvenile salmon interact with predators also attracted to the cover,” Peter Moyle, professor emeritus in the Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology Department at UC Davis, wrote in an email to Western Water. “But I would also argue that the more complex cover there is available along the major rivers, the better, especially in channelized, leveed or otherwise altered reaches.”

River Garden’s effort stems from a desire to view agricultural operations, river health and salmon preservation/restoration through a holistic lens, said Les Canter, a general partner at River Garden. Canter and others are concerned that the state of California is taking a strict regulatory approach that focuses too narrowly on river flows in its quest to update water quality downstream in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

River Garden’s effort stems from a desire to view agricultural operations, river health and salmon preservation/restoration through a holistic lens, said Les Canter, a general partner at River Garden. Canter and others are concerned that the state of California is taking a strict regulatory approach that focuses too narrowly on river flows in its quest to update water quality downstream in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

The State Water Resources Control Board in July released a final draft plan to increase water flows through the lower San Joaquin River and its tributaries — the Stanislaus, Tuolumne and Merced rivers — to prevent what it deemed “an ecological crisis, including the total collapse of fisheries.” A similar plan is being prepared for the Sacramento River and its tributaries, Delta eastside tributaries (including the Calaveras, Cosumnes and Mokelumne rivers), Delta outflows and interior Delta flows.

Not surprisingly, the idea of leaving water in the rivers has polarized opinions. Supporters of the idea say it’s vital to reinvigorate a dying ecosystem while opponents, who turned out en masse at a state Capitol protest Aug. 20, decry the plan as a “water grab.” The protest came ahead of two days of contentious hearings by the State Water Board, which deferred a decision on the San Joaquin River plan.

In an email to Western Water, State Water Board spokesman Tim Moran noted that “there are other factors, such as habitat restoration and predator suppression, but that flow is central to restoring native fisheries.” He added that the State Water Board is encouraging settlement agreements with water rights holders that would address those other factors.

“Neither of these efforts are magic bullets to stop salmon decline because salmon need help at all life stages.”

~Peter Moyle, professor emeritus in the Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology Department at UC Davis

Canter said he believes that when regulators zero in on precise numeric flow standards they neglect the important intangibles such as proper food sources and habitat for fish.

“Globally, that’s what’s missing in the dialogue right now,” he said. “The State Water Board has a very narrow directive. They have a knob they can turn and it’s a water knob [but] I don’t think anybody believes unimpaired flows is the right way to go. It would cause chaos.”

Moyle noted that regulators use increased flows “because it is an action for which they have some control (releases from dams) and it is obvious the environment has not gotten its ‘fair share’ of the water over the decades.”

However, “more water without adequate habitat with which to interact may not produce the desired results of increasing fish production. For salmon, for example, if conditions are not right for all life-history stages, restoration efforts for one life stage may not pay off if others are neglected.”

Canter said he subscribes to the idea of “reconciliation ecology,” which acknowledges that while human activity has greatly alerted the landscape, it is possible to preserve and boost the health and vitality of an ecosystem using existing infrastructure.

Canter said he subscribes to the idea of “reconciliation ecology,” which acknowledges that while human activity has greatly alerted the landscape, it is possible to preserve and boost the health and vitality of an ecosystem using existing infrastructure.

“If we can put a remote-control jeep on Mars, we can do this,” he said.

Canter, Cornwell and like-minded people in the science community embrace the idea of manipulating the floodplain environment in a manner that helps produce a bountiful buffet of tiny aquatic life-forms that are a crucial food source for juvenile salmon. The “aha” moment occurred, Canter said, several years ago with a slew of evidence highlighting the benefit of reconnecting rivers with their historical floodplains.

Through subtle tweaks to their irrigation schedule in October through the end of February, River Garden leaves water on rice-harvested fields at key depths and intervals before that water —filled with microorganic nutrients — is diverted back to the river.

The effect, Canter said, is “we are dosing the river” with fish food that would otherwise be nonexistent or at minimal levels. Previously, harvested rice fields were flooded and left that way for months as the stubble decomposed throughout the winter.

The effect, Canter said, is “we are dosing the river” with fish food that would otherwise be nonexistent or at minimal levels. Previously, harvested rice fields were flooded and left that way for months as the stubble decomposed throughout the winter.

“All we are doing is draining the fields every three to four weeks,” Cornwell said. “We are bringing water onto the landscape and watching the magic happen.”

The results are impressive. Cornwell said 100 acres of flooded rice fields can produce enough nutrients to support 135,000 juvenile salmon. River Garden is in the third and final year of the fish food experiment, with the next step being the quantification of the extent and reach of the food bloom in the mainstem Sacramento River. He’s already looking ahead to the next phase.

“We prove the concept, then start adding more acreage in fish food production,” Cornwell said.

While River Garden is physically disconnected from the river, other floodplain sites remain along the river where the possibility exists of providing salmon a direct stopover to fatten up. More than 500,000 acres annually are devoted to rice farming in the Sacramento Valley. It may be impossible to re-establish the environment the fish once traveled — from the cold, upper reaches of the Sacramento River and its tributaries all the way to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta — but the idea is to create “hot spots” of food productivity along the route to make life for the fish a little easier.

“We can’t re-connect them all, but we can mimic floodplains on a rice field,” Cornwell said. “It’s a lake we can control.”

The approach has buy-in from fish experts. Moyle with UC Davis wrote there is a growing consensus that raising salmon on floodplains can benefit populations, although tracking floodplain-reared fish to see if they return at higher rates than other salmon has yet to be done.

A major problem he noted, is getting wild-spawning salmon onto the flooded fields.

What River Garden and others are doing will only succeed if the activities do not become entangled in burdensome regulatory permitting, Canter said, noting that “we need to keep this very simple. If it becomes too hard … you can’t get traction.”

Cornwell said the hope is that by proving the habitat restoration and fish food projects work, they might attract water-bond financing that leverages local money to expand the footprint of even more fish-friendly endeavors. What’s needed, he said, is money to support ongoing monitoring and possibly to assist smaller-acreage growers who wish to undertake projects.

Cornwell said the hope is that by proving the habitat restoration and fish food projects work, they might attract water-bond financing that leverages local money to expand the footprint of even more fish-friendly endeavors. What’s needed, he said, is money to support ongoing monitoring and possibly to assist smaller-acreage growers who wish to undertake projects.

“If we could get 50,000, 60,000 or 100,000 acres signed up overnight, then we’d see a landscape-sized change,” he said.

Abrupt change in the population of all the salmon runs will not happen overnight, but providing them refuge and food can only help, according to Moyle. Finding money to expand such efforts is worthwhile.

“Neither of these efforts are magic bullets to stop salmon decline because salmon need help at all life stages,” Moyle wrote. “But they are clearly bold moves that will contribute to long-term survival of salmon populations in the Central Valley.”

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Learn more

The Water Education Foundation has written extensively about fish and flood challenges in the Sacramento Valley. These readings may add to your understanding.

Western Water: Preservation and Restoration: Salmon in Northern CaliforniaWestern Water: Levees and Flood Protections: A Shared Responsibility

Western Water: Making a Future for Fish: Preserving and Restoring Native Salmon and Trout