California Gold Rush and Today’s Water

More than 100 years ago, California’s Gold Rush left a toxic legacy that continues to cause problems in Northern California watersheds.

The discovery of gold in John Sutter’s millrace at Coloma in the 1840s drew people from around the globe.

Over the course of decades, intense efforts were focused on washing and prying gold from the hills of the Sierra Nevada.

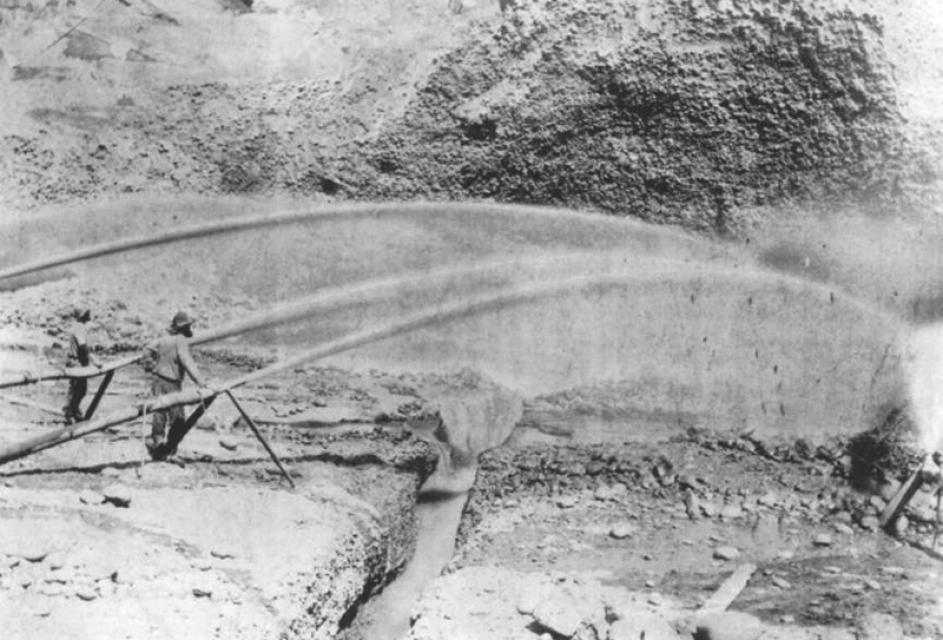

Mercury was an essential commodity of gold mining, as it greatly increased the recovery efficiency of primitive mining technology. Mercury, which was plentiful from deposits in the nearby Coast Range, acts as a magnet of sorts, drawing gold to it in a ready-made, easily recoverable amalgam from rock, gravel or soil. Once gathered, miners heated the amalgam to separate the two metals. Pressure washing from water cannons, used to separate gold from other minerals, also flushed toxins into the water supply.

More than a century later, the miners have long since departed, but the mercury remains, with harmful consequences. While some mercury is naturally occurring, escaping from near surface deposits, volcanoes and hot springs, the majority of what exists in the environment today is the result of industrial activity.

Relatively benign in its inorganic form, mercury’s organic cousin methylmercury is a persistent, bioaccumulative toxin that moves through the food chain and can build up in fish tissue to levels that could pose serious health threats to people who eat large amounts of contaminated fish.

Methylmercury’s damaging effects to the human body, particularly its harm to unborn children, has propelled it to being a prime concern among water quality and public health regulatory agencies.

In Northern California, Gold Rush-era mercury contaminated both sides of the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys and is difficult to remove. Some estimates are that 10 percent of the state’s landmass would have to be dredged or bulldozed to remove all contamination sources.

Faced with such a daunting scenario, efforts are being focused toward increasing the understanding of mercury’s fate in the environment and the most effective ways to keep it from embarking on its toxic path.

Oversight of the issue rests with the federal Food and Drug Administration and Environmental Protection Agency, and in California, the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. The agencies emphasize the nutritional benefits of eating fish, but encourage women, especially pregnant women, to modify the amount and type of fish they consume.