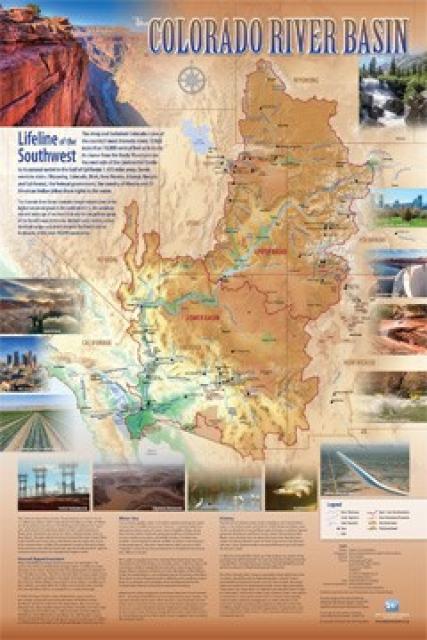

Imperial Valley

The Imperial Valley in the

southeastern corner of California receives the Colorado River

Basin’s single-largest share of water to support much of the

nation’s fruit and vegetable supply and hay for the

The Imperial Valley in the

southeastern corner of California receives the Colorado River

Basin’s single-largest share of water to support much of the

nation’s fruit and vegetable supply and hay for the

cattle and dairy industries.

The All-American Canal cuts across the desert for more than 80 miles to deliver the Colorado River water. The Imperial Irrigation District (IID) holds water rights dating to 1901. In 2022, Imperial County’s agricultural production totaled more than $2.6 billion.

The Imperial Valley is at once a success story and a cautionary tale of desert reclamation.

In the early 1900s, canals and aqueducts carrying Colorado River water helped transform much of the landscape into a rich agricultural area. The rupture of an irrigation canal in 1905 filled an ancient lakebed in the Colorado Desert, creating California’s largest lake, the Salton Sea.

By the 1920s, accumulating salts and a rising water table put some cropland out of production and threatened the productivity of thousands more acres.

A $2.5 million bond issue passed in 1922 allowed the IID to build a drainage system to collect water from farms and convey it to the Salton Sea. To date, 38,000 miles of subsurface tile drains have been installed beneath 500,000 acres or more than 95 percent of Imperial Valley farmland. About 1 million acre-feet of agricultural drainage water flow to the Salton Sea annually from IID, mostly from Imperial County farms.

Two northward-flowing river channels, the New and the Alamo, became the system’s main drainage conveyance channels. The Salton Sea also receives irrigation drainage from farms in northern Mexico and California’s Coachella Valley.

The Salton Sea

Over time, nutrients and salt from agricultural runoff built up in the Salton Sea, helping nurture a vibrant ecosystem of fish and birds but creating water and air pollution problems. Because the sea has no outlet, the salts concentrated, making the lake saltier than ocean water.

The high concentration of salts and trace minerals like selenium can be toxic to birds and fish.

The sea became a central issue in negotiations over the Quantification Settlement Agreement that would provide large, long-term water transfers from the Imperial Valley to cities in the Coachella Valley and San Diego County.

The deal lessened California’s

dependency on the overdrawn Colorado River, but farm runoff the

to Salton Sea dropped sharply as Imperial Valley farmers adopted

more efficient irrigation systems. With less farm drainage, the

lake has steadily receded.

The deal lessened California’s

dependency on the overdrawn Colorado River, but farm runoff the

to Salton Sea dropped sharply as Imperial Valley farmers adopted

more efficient irrigation systems. With less farm drainage, the

lake has steadily receded.

Dust from the exposed lakebed created for Imperial Valley some of the worst air quality in California. A 2019 survey found that 22 percent of children in the region have asthma, nearly three times the national average. About 100,000 people live within 10 miles of the sea.

California law makes the state Natural Resources Agency largely responsible for fixing environmental problems at the lake. But the agency stalled on doing the repairs for years. Imperial Irrigation District threatened to end its water transfers due to the lack of restoration progress.

In 2017 – 14 years after the signing of the Quantification Settlement Agreement – the resources agency released the Salton Sea Management Plan to create 30,000 acres of wetlands to control dust and revitalize habitat around the shrinking sea.

More than 8,000 acres of ponds for fish-eating birds will be filled by pumping water from the Salton Sea and mixing it with fresh water from the New River, providing a tolerable salinity level for fish. The plan includes a ditch to reroute agricultural drainage around the ponds to protect endangered desert pupfish.

The restoration plan received a major boost in 2022 when the Interior Department announced it would allocate up to $250 million for Salton Sea projects from Inflation Reduction Act funds, in exchange for Colorado River conservation efforts by water districts serving the Imperial and Coachella valleys. As of 2023, the state and federal governments had committed more than $830 million to the program.

The lack of long-term funding for maintaining the restoration is a major sticking point in discussions over the post-2026 set of Colorado River operating rules. If California agrees – or is forced – to reduce its river use, the Salton Sea may receive less irrigation drainage from the Imperial Valley, potentially slowing its environmental restoration.

Updated July 2024