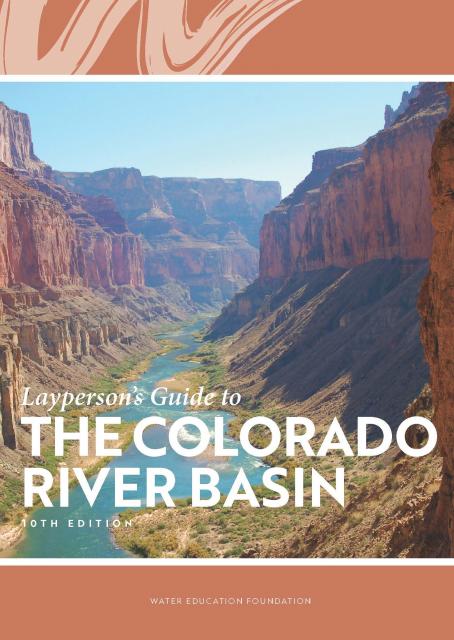

Colorado River

The turbulent Colorado River is one

of the most heavily regulated and hardest working rivers in the

world.

The turbulent Colorado River is one

of the most heavily regulated and hardest working rivers in the

world.

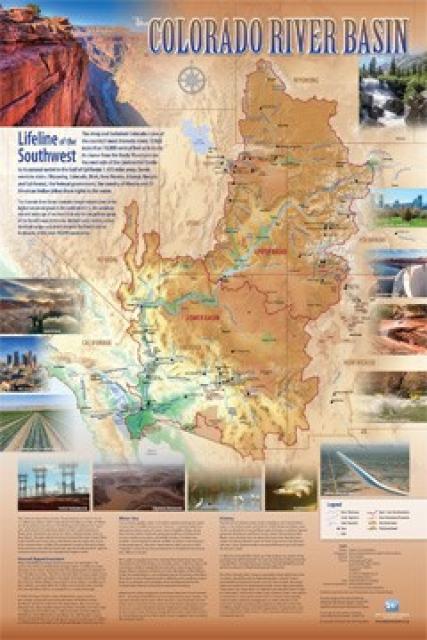

Geography

The Colorado falls some 10,000 feet on its way from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California, helping to sustain a range of habitats and ecosystems as it weaves through mountains and deserts.

From its headwaters in Colorado and Wyoming, the 1,450-mile-long river and its tributaries pass through parts of seven states and serves Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming along with 30 tribal nations. The river also winds through part of the Republic of Mexico before reaching, in wet years, the Gulf of California.

The chief tributary of the Colorado River is the Green River, a 730-mile-long artery that begins in the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming, winds through Colorado and Utah before joining the Colorado River in Canyonlands National Park in southern Utah.

Canyonlands and the Grand Canyon are among 11 National Park Service units that lie along the Colorado River and its tributaries, including Arches National Park, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

The mainstem of the Colorado River runs for about 300 miles through Marble Canyon and the Grand Canyon. The powerful forces of erosion have carved through 2 billion years of the earth’s geologic history at the Grand Canyon. Layers of limestone, sandstone, shale, granite, and schist make up the Grand Canyon’s rock sequences.

Serving as the “lifeline of the Southwest,” the Colorado River provides water to 40 million people and more than 5 million acres of farmland in a region encompassing some 246,000 square miles.

The canyon’s depth varies from almost a vertical mile along the South Rim to almost 6,000 feet at other locations. The canyon’s width ranges from an average of 10 miles across near Grand Canyon Village but may be as wide as 18 miles across from rim to rim.

Along the Colorado River’s journey from its headwaters to the Gulf of California, almost every drop of its water is allocated for use.

Colorado River Overview

The Colorado River has been tapped for use by humans for at least 1,500 years.

Today, more water is exported from the Colorado River Basin than any other river basin in the United States.

In Colorado, water is diverted over the Continental Divide to supply Denver and other Front Range cities. Water is diverted in Utah to the Salt Lake Valley, in New Mexico to the Rio Grande Basin to serve Albuquerque, in Wyoming to serve Cheyenne and in California to the southern coastal plain of Los Angeles and San Diego.

Much of the river’s water is diverted for irrigated agriculture, including the Palo Verde, Imperial and Coachella valleys in California, in central Arizona and the Yuma region, and in Mexico. (For a more in-depth look at the various Colorado River stakeholders, see the Layperson’s Guide to the Colorado River.)

As part of its diverse environments, the Colorado River boasts more than 30 fish species found nowhere else in the world. However, 50 percent of all native fish in the Colorado Basin have either gone extinct or are considered vulnerable.

The river itself was originally muddy, brown and seasonally warm (the source of its name Colorado) but is now clear and cold due to dams and reservoirs.

The Colorado River was the last major area of the 48 contiguous states to be explored. In 1869, an expedition led by John Wesley Powell first explored and mapped the Colorado and Green rivers.

In 1905, the Colorado River broke through a series of dikes built to serve agriculture in the Imperial Valley, flooding an ancient seabed as it had done so historically and forming today’s Salton Sea.

Recreation is also a significant part of the Colorado River system. The Colorado River Basin is used by millions of people annually for activities ranging from rafting to snow sports and generates billions of dollars in revenue.

Colorado River Agreements

Colorado River water is shared by states, the federal government, American Indian tribes and Mexico, resulting in many compromises, interstate compacts, a U.S. Supreme Court decree and an international treaty. Collectively, this is known as the Law of the River.

The need to equitably distribute the river’s resources resulted in the historic 1922 Colorado River Compact. The Compact divided the river into Upper and Lower Basins and apportioned the right to exclusive beneficial consumptive use of 7.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River system in perpetuity to the Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) and the Lower Basin (Arizona, California, and Nevada).

The Compact provides that the Upper Basin states will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry, Arizona, the dividing point between Upper and Lower Basins, to be depleted below an aggregate of 75 million acre-feet for any period of 10 consecutive years.

The Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 authorized construction of a dam along the river, construction of the All-American Canal to connect the river to the Imperial and Coachella valleys and it also divided the water among the Lower Basin states. Congress in 1947 officially designated the dam as Hoover Dam.

In 1944, a U.S.-Mexico treaty resulted in an annual 1.5 million acre-feet allocation to Mexico. Four years later, the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact created the Upper Colorado River Commission and apportioned the Upper Basin’s 7.5 million acre-feet among Colorado (51.75 percent), New Mexico (11.25 percent), Utah (23 percent), and Wyoming (14 percent).

The 1956 Colorado River Storage Project Act authorized construction of the Wayne N. Aspinall Unit in Colorado, the Flaming Gorge Unit in Utah, the Navajo Unit in New Mexico and the Glen Canyon Unit in Arizona. In 1968, the Colorado River Basin Project Act authorized construction of the Central Arizona Project (CAP) and made the priority of the CAP water supply subordinate to California’s apportionment in times of shortage. It also directed the secretary of the interior and the basin states to prepare long-range operating criteria for the river’s reservoirs.

The 2003 Quantification Settlement Agreement incorporated an Imperial Valley to San Diego County water transfer. This was followed by a 2007 agreement among the seven Colorado Basin states that established a new water release formula between Lake Powell and Lake Mead to help meet increased demand for water. (These 2007 agreements governing Colorado River operations expire in 2026, and the seven states and the federal government are negotiating a new set of post-2026 operating guidelines.)

In 2012, the U.S. and Mexico signed Minute 319. Minute 319 established new rules for sharing Colorado River water through a five-year pact. Mexico, with limited storage capacity, would be able to store some of its Colorado River water in Lake Mead. In exchange, should a shortage be declared in the Lower Basin, less water would be sent to Mexico.

A continuation of Minute 319, called Minute 323, was finalized in September 2017. One focus of Minute 323 is to provide water to habitat restoration sites, and to maintain and expand them to as many as 4,300 acres. Mexico will continue to store water in Lake Mead and both governments will provide funding and other resources for research projects along the border and throughout the region.

Minute 323 requires that the U.S. contribute $31.5 million to conservation projects in Mexico focused on improving infrastructure. These projects are expected to save about 200,000 acre-feet of water each year. The money will come not only from the U.S. government but from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, Southern Nevada Water Authority, Imperial Irrigation District and Central Arizona Water Conservation District. In return for their funding, these water agencies will receive a portion of the saved water. In addition to funding for conservation projects, the U.S. government and nongovernmental agencies will fund $18 million for the habitat restoration and monitoring.

The idea of a Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) emerged in 2013 as an overlay to the 2007 shortage-sharing agreement. After the intense drought of the early 2000s, stakeholders had breathed a sigh of relief with a high flow on the river in 2011, only to be followed by the lowest consecutive years on record. Suddenly, the possibility of Lake Mead dropping to dead pool (when the water level is so low that it cannot drain by gravity through Hoover Dam’s outlets) didn’t seem far-fetched.

After six years of negotiations, the DCP was signed into law in 2019. The Upper Basin portion of the plan protects elevations at Lake Powell and authorizes storage of conserved water in the Upper Basin. The Lower Basin DCP requires Arizona, California and Nevada to contribute additional water to Lake Mead storage and creates additional flexibility to incentivize voluntary conservation of water to be stored in Lake Mead.

Yet persistent drought continues to strain the river and the DCP has proved insufficient to protect water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. In 2022, the first-ever shortage declaration required additional reductions in use for Arizona and Nevada, and federal officials announced even deeper cuts in use would be required throughout the Colorado River Basin in 2023 and beyond.

Current Colorado River Challenges

Since the 1990s, many programs have been underway to boost endangered species and restore some riverine habitat. Both wildlife and the environment have been impacted by water diversion and development such as dams.

Since 2000, the Colorado River Basin also has experienced drought, which has included some of the driest conditions on record. Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam have both helped the Colorado River Basin weather the drought, though the combined water storage in the reservoirs they create has declined by more than 60 percent. The drought has led to tremendous disparity between high and low flows in the last decade.

Looking ahead, some experts predict climate change will cause the Colorado River Basin to become drier and warmer with less snowfall and runoff reducing water supplies. That prospect, combined with future projections of continued urban growth, has generated significant concern over how the Colorado River will meet future water demands.

With these issues in mind, in 2012 the Bureau of Reclamation published the Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study to help provide a road map for the future.

The study projected a wide range of potential long-term imbalances between supply and demand by 2060, with a median figure of 3.2 million acre-feet. The study noted that the amount of water available and the changes in demand during the next 50 years are “highly uncertain” and that the potential impacts of future climate change and variability “further contribute to these uncertainties.”

In 2018, the Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Tribal Water Study was released. That study described how tribes use their water, how future water development could occur and the potential effects of future tribal water development on the Colorado River system. The study identified challenges related to the use of tribal water and explored opportunities that provide a wide range of benefits to both Partnership Tribes and other water users.

Another 2018 study, the U.S. Global Change Research Program’s Fourth National Climate Assessment, concluded that Earth’s climate is changing rapidly compared to the pace of natural variations that have occurred throughout its history, with greenhouse gas emissions largely the cause.

Much of what the assessment expects to happen in the Colorado River Basin depends on several variables, including changes in water demand and the rate of greenhouse gas emissions. According to the assessment, under certain scenarios, higher temperatures would cause more frequent and severe droughts in the Southwest, including megadroughts — dry periods lasting 20 years or longer.

Projected substantial reductions in snowpack and increased rain, earlier runoff and warmer late-season stream temperatures combined with an increasing population in Southern California, which imports most of its water, would increase the probability of future water shortages, according to the assessment.