150 Years After John Wesley Powell Ventured Down the Colorado River, How Should We Assess His Legacy in the West?

WESTERN WATER Q&A: University of Colorado’s Charles Wilkinson on Powell, Water and the American West

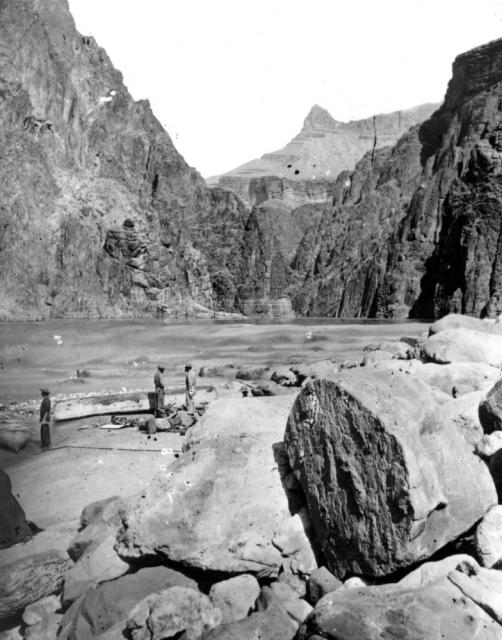

We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls ride over the river, we know not. Ah, well! We may conjecture many things.

~John Wesley Powell

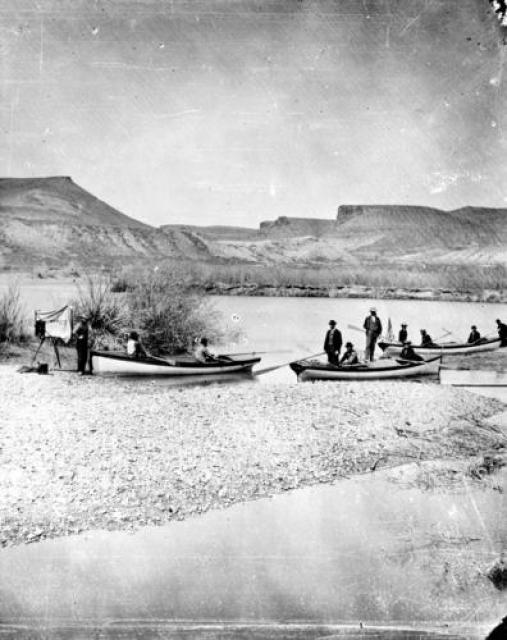

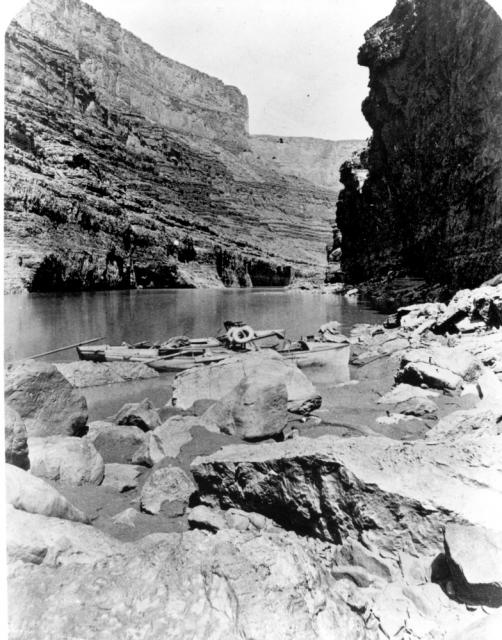

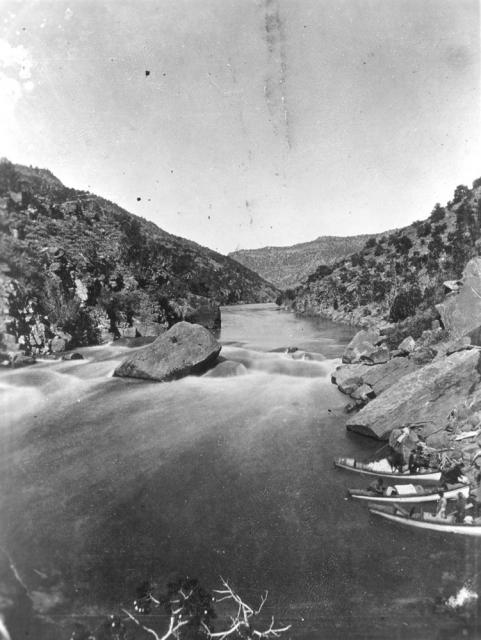

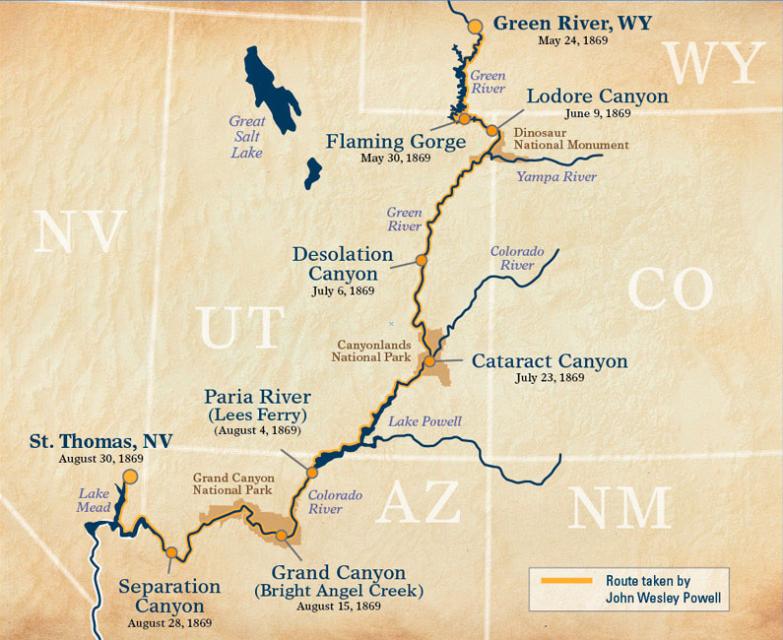

Powell scrawled those words in his journal as he and his expedition paddled their way into the deep walls of the Grand Canyon on a stretch of the Colorado River in August 1869. Three months earlier, the 10-man group had set out on their exploration of the iconic Southwest river by hauling their wooden boats into a major tributary of the Colorado, the Green River in Wyoming, for their trip into the “great unknown,” as Powell described it.

Powell scrawled those words in his journal as he and his expedition paddled their way into the deep walls of the Grand Canyon on a stretch of the Colorado River in August 1869. Three months earlier, the 10-man group had set out on their exploration of the iconic Southwest river by hauling their wooden boats into a major tributary of the Colorado, the Green River in Wyoming, for their trip into the “great unknown,” as Powell described it.

Powell’s trip down the Colorado River and his subsequent account are a staple of the history of the American West and a key moment in the understanding of the region’s geology and hydrology. One hundred and fifty years after Powell and his party began their trip on May 24, 1869, the magnitude of his accomplishment remains fascinating. After enduring a harrowing ride through pounding rapids while surviving on near-starvation rations, six exhausted men emerged from the 930-mile journey on Aug. 30, 1869. (One man quit after a month, while three others departed on Aug. 28, never to be seen again.) Powell would return in 1871 for a second trip.

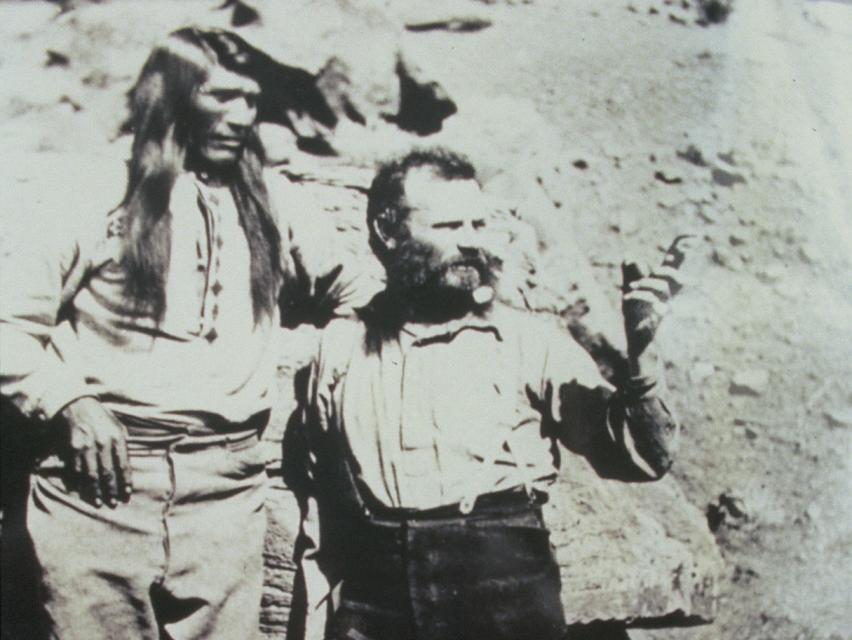

University of Colorado Professor Emeritus Charles Wilkinson has written about Powell and his legacy, including the foreword to an upcoming book on Powell by a collection of contributors called “Vision & Place: John Wesley Powell & Reimagining the Colorado River Basin.” Wilkinson described the Western icon and one-armed Civil War veteran as a complex character, a larger-than-life person and an early visionary of wise water use in an arid West. Powell, the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey, “could be viewed as an early climate scientist,” according to USGS’ official biography, because of his belief that lands west of the 100th meridian were not generally suitable for agricultural development but for a small percentage. He advocated for organizing settlements around water and watersheds, which would encourage collaboration and local control and force water users to conserve.

University of Colorado Professor Emeritus Charles Wilkinson has written about Powell and his legacy, including the foreword to an upcoming book on Powell by a collection of contributors called “Vision & Place: John Wesley Powell & Reimagining the Colorado River Basin.” Wilkinson described the Western icon and one-armed Civil War veteran as a complex character, a larger-than-life person and an early visionary of wise water use in an arid West. Powell, the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey, “could be viewed as an early climate scientist,” according to USGS’ official biography, because of his belief that lands west of the 100th meridian were not generally suitable for agricultural development but for a small percentage. He advocated for organizing settlements around water and watersheds, which would encourage collaboration and local control and force water users to conserve.

“I tell you gentlemen you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not enough water to supply the land,” Powell told an audience of farmers and developers in October 1893, a year before he resigned from the USGS.

Wilkinson spoke recently with Western Water about Powell and his legacy and how Powell might view the Colorado River today.

WW: How did you first become acquainted with Powell’s story?

CHARLES WILKINSON: A lot of people of my vintage give the same answer, which is Wallace Stegner’s book. (“Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West.”) I proceeded to read about half of Stegner’s other works in a month. Finally, I wrote him a letter. He said come down and we’ll talk, and we became close friends. [Former Secretary of the Interior] Bruce Babbitt said Stegner’s book was the “rock that came through the window” for him, and I think Powell is somebody you can look at that way. He opened so much for us. He was the Lewis and Clark of the Southwest. The country didn’t know about the region and Powell picked up so much information about it.

WW: What’s the context in which we view Powell and his journey today?

WILKINSON: It’s the specifics of going down the canyon — the sense of daring, bravery, ambition and looking out into the future. Along the way, he’s meeting with Indian tribes, Hispanic communities, Mormon communities and so you are starting to get a sense of land-based people and diverse societies. Powell believed in cooperation in water policy and public land policy. On the public land side, he had ideas about homesteading. He favored it, but the problem in the mid-19th century was the big combines were the ones benefiting because they would find ways to buy up homestead land and make money out of it. Also, there was this notion that the U.S. wanted everyone to move west and there were a whole lot of people coming out saying, ‘there’s no rain out here through the summer’ and everything was brown instead of green. Powell favored a truth-in-lending approach toward homesteading so that potential homesteaders knew what they were in for.

WILKINSON: It’s the specifics of going down the canyon — the sense of daring, bravery, ambition and looking out into the future. Along the way, he’s meeting with Indian tribes, Hispanic communities, Mormon communities and so you are starting to get a sense of land-based people and diverse societies. Powell believed in cooperation in water policy and public land policy. On the public land side, he had ideas about homesteading. He favored it, but the problem in the mid-19th century was the big combines were the ones benefiting because they would find ways to buy up homestead land and make money out of it. Also, there was this notion that the U.S. wanted everyone to move west and there were a whole lot of people coming out saying, ‘there’s no rain out here through the summer’ and everything was brown instead of green. Powell favored a truth-in-lending approach toward homesteading so that potential homesteaders knew what they were in for.

WW: What did Powell contribute to our modern thinking about water in the West?

WILKINSON: David Getches [former dean of the University of Colorado Law School] wrote the best legal book about the Colorado River and he called for community governance, but he got that from Powell. The idea of the people of the watershed and the different large river tributaries being communities and being able to have their own values evidenced in land policy and water policy really dates to Powell. Would Powell be an environmentalist? Not exclusively in any way explicitly. He was kind of just before John Muir … and during his formative years … environmentalism in any modern sense hadn’t come about yet. He never would have argued for using every drop of the river, but he thought agriculture was the future of the West, the Jeffersonian ideal, and so he saw Western rivers and the Colorado River watershed as having a lot of diversions from it for agriculture.

WILKINSON: David Getches [former dean of the University of Colorado Law School] wrote the best legal book about the Colorado River and he called for community governance, but he got that from Powell. The idea of the people of the watershed and the different large river tributaries being communities and being able to have their own values evidenced in land policy and water policy really dates to Powell. Would Powell be an environmentalist? Not exclusively in any way explicitly. He was kind of just before John Muir … and during his formative years … environmentalism in any modern sense hadn’t come about yet. He never would have argued for using every drop of the river, but he thought agriculture was the future of the West, the Jeffersonian ideal, and so he saw Western rivers and the Colorado River watershed as having a lot of diversions from it for agriculture.

WW: Does the attention paid to Powell’s story come at the expense of others?

WILKINSON: When we talk about Powell, we talk about what he had to offer us. One was intellectual ambition. Powell came up with comprehensive plans for the settlement of the West that were beyond what anyone was thinking. He did think big. He thought big about going down the river in the first place. His policy proposals were easily the most important work done in the 19th century in terms of Western land. He was a man who refused to have any limitations to his intellect and there wasn’t any idea he didn’t want to take on. He wanted to take on the biggest and toughest ones he could find.

WILKINSON: When we talk about Powell, we talk about what he had to offer us. One was intellectual ambition. Powell came up with comprehensive plans for the settlement of the West that were beyond what anyone was thinking. He did think big. He thought big about going down the river in the first place. His policy proposals were easily the most important work done in the 19th century in terms of Western land. He was a man who refused to have any limitations to his intellect and there wasn’t any idea he didn’t want to take on. He wanted to take on the biggest and toughest ones he could find.

With Indians, it’s a big subject and as a starting point, I think you have to say Powell had a very unfortunate impact on Indian policy. He was the head of the Bureau of Ethnology and his ethnologies were very patronizing. He didn’t think of governance for tribes. Of course, today, tribes are known as sovereign. He has these immense proposals of different kinds for how to govern Western lands and paid a lot of attention to water rights generally, but he never proposed any right for tribes, so this is a black mark against him.

WW: How would he view the issues that exist on the Colorado River today?

WILKINSON: We had [with the Drought Contingency Plan] a partial approach toward reconciling Upper Basin and Lower Basin water interests and I think Powell would have liked that very much because it fits with his idea of local government and people of the watershed making decisions. He favored reclamation, and the Reclamation Act of 1902 was partly his work. But I can’t help but feel that the way it spun out of control with so much development on so many rivers, that he would have thought it was out of proportion. But who can say?

The best way to go about Powell is to recognize his general philosophical position and be inspired that somebody could do so much conceptualizing about what the West ought to be. It tells us that we should think big. His belief in science is something we should really respect. He was the person who started the use of public science in American natural resource management, and that’s an example of a person thinking big.

Distinguished University Professor, Moses Lasky Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Colorado Law School.

Age: 77

Education: B.A., Denison University (1963); LL.B., Stanford University (1966)

Notable:

- Special counsel to Interior Department for the drafting of the 1996 presidential proclamation establishing the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah.

- Special adviser to the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition in the creation of the Bears Ears National Monument, proclaimed in 2016.

- Author of 14 books on law, history and society in the American West.

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.