California Spent Decades Trying to Keep Central Valley Floods at Bay. Now It Looks to Welcome Them Back

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: Floodplain restoration gets a policy and funding boost as interest grows in projects that bring multiple benefits to respond to climate change impacts

Land and waterway managers labored

hard over the course of a century to control California’s unruly

rivers by building dams and levees to slow and contain their

water. Now, farmers, environmentalists and agencies are undoing

some of that work as part of an accelerating campaign to restore

the state’s major floodplains.

Land and waterway managers labored

hard over the course of a century to control California’s unruly

rivers by building dams and levees to slow and contain their

water. Now, farmers, environmentalists and agencies are undoing

some of that work as part of an accelerating campaign to restore

the state’s major floodplains.

At the Dos Rios Ranch Preserve near Modesto, crews with the statewide conservation nonprofit River Partners have set back levees along eight miles of the San Joaquin and Tuolumne rivers to invite seasonal flooding. Beside the Sacramento River, at Hamilton City north of Sacramento, a levee setback and habitat restoration project is opening up 1,361 acres to periodic inundation. The crown jewel in the state’s push for restored floodplains might be the ongoing projects within the Yolo Bypass near Sacramento. Here, advocates – including local farmers and fish biologists – hope to adjust key levees along the vast bypass so that Sacramento River water can more routinely inundate more than 20,000 acres of historic floodplain and, through a related project, expand that floodplain by 900 acres.

These are just a few of dozens of projects that together could add tens of thousands of acres to the Central Valley’s existing floodplain acreage. The hope, shared by stakeholders who have traditionally fought over water and land, is to rebuild habitat for fish, birds and other wildlife while simultaneously providing benefits, like improved flood protection and groundwater recharge, for towns and farms.

These ideas began coalescing into a field of science all its own in the 1990s and some projects lifted off the ground. Still, because of permitting delays and the complex logistics of remodeling the landscape, progress has remained sluggish.

That could change, though. In the past several years, both policy support and funding for this kind of multi-benefit floodplain restoration has gained momentum. Leaders and lawmakers have taken action to remove regulatory and bureaucratic hurdles, while state policy guides for addressing climate change and flood risk in the Central Valley have incorporated “green infrastructure” into their planning. Priming these efforts for takeoff is the recently approved state budget, which includes tens of millions of dollars for floodplain projects that offer distinct benefits to different stakeholder groups.

“The concept of multiple benefits has made floodplain restoration very appealing,” said Jeffrey Mount, a watershed expert and senior fellow with the Public Policy Institute of California. “Basically, everyone’s on board.”

“The concept of multiple benefits has made floodplain restoration very appealing.”

Jeffrey Mount, senior fellow with the Public Policy Institute of California.

The rapid decline of the Delta ecosystem, including its fish populations, has coaxed stakeholders to the negotiating table. So has the calamitous fallout of climate change, which is hitting home and fueling a sense of urgency around landscape adaptation measures. Drought now gripping California is forcing new approaches to distributing surface water and managing the use of groundwater. On the wetter side of climate change, Oroville Dam came close to bursting in the state’s last very wet year, 2017, and last month’s torrential atmospheric river was a reminder that disastrous floods are sure to come. Nature-based solutions, according to officials in numerous offices, will be essential in absorbing the deluges.

“The way to do it is move back the levees and make the rivers bigger,” said Tim Ramirez, a board member with the Central Valley Flood Protection Board, a state agency that oversees the valley’s flood risk reduction system.

Sounding the Flood Alarm

In Sacramento, officials in many offices have latched onto the

science, concepts and talking points of floodplain restoration.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom included “green infrastructure” in

his

Water Resilience Portfolio, a 140-page guide to protecting

the state’s water resources in the face of a rapidly changing

climate.  Similarly, California’s

Central Valley Flood

Protection Plan, updated in 2017, recommends “wise land use

and floodplain management” as “cost-effective means of reducing

long-term flood risk.” That document sounded the alarm that

flooding in the Central Valley is expected to increase markedly

in the decades ahead. Floods, scientists predict, will be

particularly large and damaging in the San Joaquin Valley, which

drains vast expanses of high-altitude peaks that climate change

may soon render too warm to hold substantial snow.

Similarly, California’s

Central Valley Flood

Protection Plan, updated in 2017, recommends “wise land use

and floodplain management” as “cost-effective means of reducing

long-term flood risk.” That document sounded the alarm that

flooding in the Central Valley is expected to increase markedly

in the decades ahead. Floods, scientists predict, will be

particularly large and damaging in the San Joaquin Valley, which

drains vast expanses of high-altitude peaks that climate change

may soon render too warm to hold substantial snow.

Wade Crowfoot, secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency, has emphasized the importance of floodplain revival. Late last year he introduced the “Cutting Green Tape” initiative, meant to increase the pace and scale of conservation work.

At the Department of Water Resources, Steve Rothert, manager of the Division of Multi-Benefit Initiatives – itself a recently formed office aimed at putting boots and bulldozers on the ground – said in an interview that the impacts of climate change in California and around the world have made it clear that new ways of managing the Central Valley’s water and natural resources are overdue.

“The trajectory of climate change is going to be steeper and faster than we thought it would be,” Rothert said, and floodplain projects “are going to be absolutely essential” in buffering the Central Valley against changing precipitation patterns.

From Gray to Green Infrastructure

Fortunately for advocates, funding

for such work is arriving in a fiscal flood – spillover from the

latest state budget. On Sept. 23, the governor signed a $15

billion package of 24 bills that collectively direct hundreds of

millions of dollars toward projects that offer flood protection,

groundwater recharge and habitat benefits.

Senate Bill 155 provides $593 million in the 2022–23 fiscal

year and $175 million in the year following to the California

Natural Resources Agency “to support programs and activities that

advance multi-benefit and nature-based solutions.”

SB 170 provides $131.5 million to the restoration of Central

Valley river habitat, with an emphasis on multi-benefit and

climate resiliency projects.

Fortunately for advocates, funding

for such work is arriving in a fiscal flood – spillover from the

latest state budget. On Sept. 23, the governor signed a $15

billion package of 24 bills that collectively direct hundreds of

millions of dollars toward projects that offer flood protection,

groundwater recharge and habitat benefits.

Senate Bill 155 provides $593 million in the 2022–23 fiscal

year and $175 million in the year following to the California

Natural Resources Agency “to support programs and activities that

advance multi-benefit and nature-based solutions.”

SB 170 provides $131.5 million to the restoration of Central

Valley river habitat, with an emphasis on multi-benefit and

climate resiliency projects.

“We finally have money coming at the scale where we can expect population-level changes,” said Jacob Katz, a fishery biologist studying chinook salmon in the Sacramento River. Katz, with the nonprofit California Trout, has been working on the Yolo Bypass for a decade, leading unique experiments to predict just how flood-oriented restoration here could improve the plight of California’s ailing chinook salmon runs. He said that, in the wake of recent actions in Sacramento, “there is now serious momentum building” toward reconnecting rivers to their adjacent floodplains – what he and many more scientists believe will reenergize and repopulate inland aquatic ecosystems.

“We finally have money coming at the scale where we can expect population-level changes.”

~Jacob Katz, a California Trout fishery biologist.

Julie Rentner, River Partners’ president, said the government’s shift of attention from gray to green infrastructure – that is, from concrete structures to natural landscape features – combined with newly available funding could lead to thousands of acres of revitalized floodplains in the San Joaquin Valley.

“River Partners is sitting on a pipeline of projects,” she said, referring to nine sites in the San Joaquin Valley that total about 10,000 acres of land.

While state policy now prioritizes floodplain restoration, progress in revitalizing them is likely to remain slow.

“With all the people, all the agencies, and all the permitting requirements, these projects don’t move quickly,” said Carson Jeffres, a biologist with the University of California, Davis Center for Watershed Sciences. “It can be a little frustrating.”

Mount, whose colleagues at the PPIC coauthored a recent report outlining the need for faster permitting in restoration programs, echoes the sentiment.

“We only got the Resilience Portfolio a year ago,” he said, “and our agencies are glacial.”

‘Slow It, Spread It, Sink It’

When farmers and land managers lined the Central Valley’s rivers with levees in the 19th and 20th centuries, they had a clear goal in mind: Transport flood waters rapidly off the landscape, downstream toward the ocean. Large bypasses were eventually built into this system to receive river water during exceptional flood events. This highly engineered system functioned more or less as planned, containing rivers, protecting the growing town of Sacramento, and rendering most of the Central Valley’s fertile acreage useable year-round.

However, significant tradeoffs came

from such landscape overhauling, and it took decades for

Californians to recognize them. Habitat for birds was lost,

culling the huge migratory flocks that historically swept through

the Central Valley. Less obvious was the fact that fish were

similarly robbed of vital feeding and nursery grounds.

However, significant tradeoffs came

from such landscape overhauling, and it took decades for

Californians to recognize them. Habitat for birds was lost,

culling the huge migratory flocks that historically swept through

the Central Valley. Less obvious was the fact that fish were

similarly robbed of vital feeding and nursery grounds.

Preventing flooding also stifled groundwater recharge. Soil can be leaky, and when water moves slowly over it, some portion of it sinks into the Earth. This is the process that helped create the voluminous aquifers and groundwater basins under the Central Valley, where Californians draw on average 40 percent of their water – and much more in drought years. It’s also the process that inspired the snappy six-word mantra for floodplain evangelists everywhere – “Slow it, spread it, sink it.”

But that important percolation process has been removed from much of the valley. This, coupled with a free-for-all deep dive into the San Joaquin Valley’s aquifers in the 20th century, has depleted groundwater stores, with disastrous consequences. Wells by the thousands went dry in California in the last drought, and a similar outcome is happening now. Land has subsided, damaging surface infrastructure.

Restoring floodplains can be an

effective way to recharge aquifers at little cost and with other

benefits for stakeholders. However, groundwater recharge doesn’t

occur equally at every site. How it works depends on soil type. A

layer of impermeable clay beneath the alluvial deposits of the

floodplain can prevent deep recharge, ushering water horizontally

back into the river it came from. This provides a valuable

ecosystem service, potentially keeping rivers flowing high even

during drought.

Restoring floodplains can be an

effective way to recharge aquifers at little cost and with other

benefits for stakeholders. However, groundwater recharge doesn’t

occur equally at every site. How it works depends on soil type. A

layer of impermeable clay beneath the alluvial deposits of the

floodplain can prevent deep recharge, ushering water horizontally

back into the river it came from. This provides a valuable

ecosystem service, potentially keeping rivers flowing high even

during drought.

But if a floodplain is to help replenish a groundwater basin, it must sit directly above deposits of loose sand and gravel. Knowing exactly where such substrate lies can be difficult to impossible, but emerging technology, guided by researchers at Stanford University, is now providing a clear understanding of the earth’s composition under the San Joaquin Valley.

Rosemary Knight, a Stanford geophysics professor, has helped innovate mobile electromagnetic earth imaging units that can generate high-resolution maps of the subsurface zone deep underground. Already, the system has helped farmers in the Tulare Irrigation District identify soils suitable for active recharge in the 150-foot-depth zone, typically achieved by flooding orchards or fallow ground.

Now, Knight is collaborating with River Partners to identify the best sites for situating floodplain projects in the interest of recharging groundwater basins. Funding from the new state budget and allocated by recent legislation, SB 170, could support application of the imaging technology.

“This will help us get the maximum benefit out of these recharge projects,” Knight said.

The Storm That Changed Perceptions

The other major human benefit of restoring floodplains is flood control. Many of the levees in the Central Valley were built by the Army Corps of Engineers to channelize the watershed and rapidly funnel mountains’ worth of mining tailings out of the valley, and into the ocean, to prevent clogging of shipping lanes.

“It worked well, but it wasn’t a very

effective way to protect against flooding,” said Leslie

Gallagher, executive officer of the Central Valley Flood

Protection Board.

“It worked well, but it wasn’t a very

effective way to protect against flooding,” said Leslie

Gallagher, executive officer of the Central Valley Flood

Protection Board.

Today, levees as flood protection are seen in many cases by floodplain scientists as outdated artifacts of old-school engineering. Ramirez, at the Flood Protection Board, said a key turning point in the transition from gray to green infrastructure came with a warm and powerful winter storm that hit Northern California in the last days of 1996. Over the course of a week, more than three feet of rain fell at high elevations. Such unseasonal rainfall melts the snow it lands on, significantly increasing the resulting runoff. Downstream, the lowlands of the Central Valley and Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, though guarded by levees, experienced major flooding.

Such storms are expected to grow more frequent as the climate warms.

“Those rain-on-snow events are going to be very problematic,” Ramirez said.

Setting levees back from the river’s edge increases the basin’s volume, reducing peak flows and the chances of a rupture in areas where levees must be kept relatively close together, like in urban areas.

Making levees higher is seen as a risky enterprise and ultimately ineffective.

“That just sends the problem downstream,” Rothert, at the Department of Water Resources, said.

The Yolo Bypass and other flood

containment basins are currently functional in reducing flood

severity in developed areas downstream, but it’s past time,

Rothert said, for upgrades. A package of projects outlined in the

Central Valley Flood Protection Plan will, he said, substantially

increase the capacity of the Yolo and Sacramento bypasses,

reducing flood-stage waters by two vertical feet in Sacramento.

These projects kicked off in May, and more are scheduled to break

ground next year.

The Yolo Bypass and other flood

containment basins are currently functional in reducing flood

severity in developed areas downstream, but it’s past time,

Rothert said, for upgrades. A package of projects outlined in the

Central Valley Flood Protection Plan will, he said, substantially

increase the capacity of the Yolo and Sacramento bypasses,

reducing flood-stage waters by two vertical feet in Sacramento.

These projects kicked off in May, and more are scheduled to break

ground next year.

“We have to make the bypasses bigger,” Rothert said.

There are different approaches to floodplain restoration in the Central Valley. Some projects involve setting back levees to restore historic floodplains while others entail creating small spillways that allow riverside farmland to flood in the wet season. PPIC’s Mount considers the former – levee setbacks and restored floodplain – as the more effective approach for reducing flood risk, but very little work of this sort has been completed in California. A few levees have been shifted along the Feather and Bear rivers, Mount said. Otherwise, the most talked-about projects involve “engineering leaks in the system to get water onto agricultural floodplains,” as seen in the plans for encouraging flooding of the large Sacramento Valley bypasses – not the same thing, Mount said, as truly restoring a floodplain.

“We still don’t see the big levee setback projects that were advocated for more than 20 years ago,” he said.

Helping the Chinook

Still, most stakeholders are cheering on the plans to notch the Fremont Weir, a low dam built into the levee, and encourage routine and prolonged flooding of the Yolo Bypass – a simple flooding cycle that many believe could help build back the Central Valley’s dwindling chinook salmon.

Though the valley’s rivers mark the southern extent of the chinook’s geographic range, this hot, arid zone was nonetheless the stronghold of the species. Between 1 million and 2 million adult chinook are estimated to have historically migrated up the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers to spawn each year, and key to their success here were the high mountains of the Sierra Nevada that shed cold water into the valley all summer combined with rich riverside floodplains.

Today, much of that habitat has been lost, sacrificed to Western industries, and the chinook salmon’s numbers have declined precipitously from historic highs.

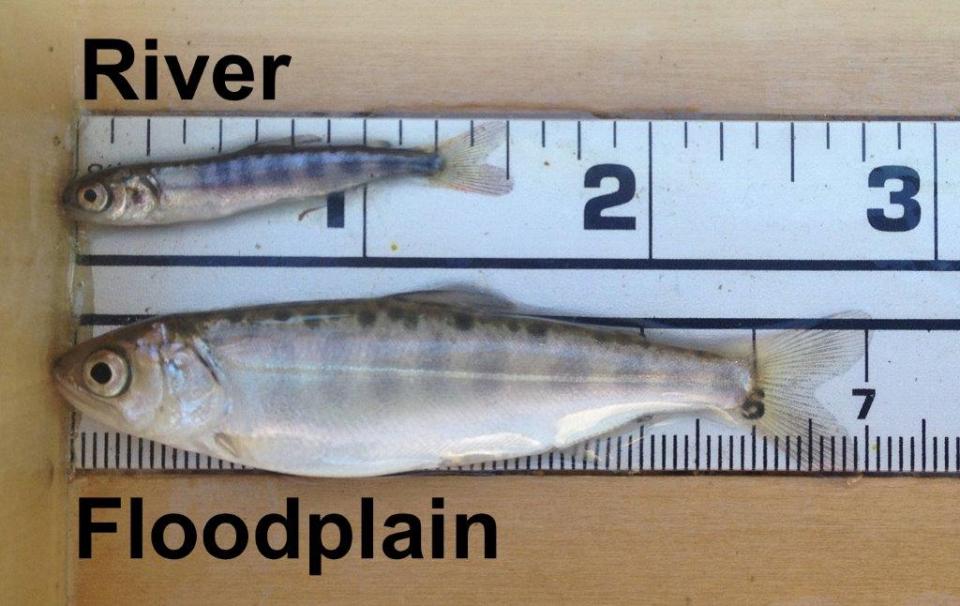

SIDEBAR: Creating A Floodplain Buffet for Salmon Smolts

By Alastair Bland

Biologists have designed a variety

of unique experiments in the past decade to demonstrate the

benefits that floodplains provide for small fish. Tracking

studies have used acoustic tags to show that chinook salmon

smolts with access to inundated fields are more likely than

their river-bound cohorts to reach the Pacific Ocean. This is

because the richness of floodplains offers a vital buffet of

nourishment on which young salmon can capitalize, supercharging

their growth and leading to bigger, stronger smolts.

Biologists have designed a variety

of unique experiments in the past decade to demonstrate the

benefits that floodplains provide for small fish. Tracking

studies have used acoustic tags to show that chinook salmon

smolts with access to inundated fields are more likely than

their river-bound cohorts to reach the Pacific Ocean. This is

because the richness of floodplains offers a vital buffet of

nourishment on which young salmon can capitalize, supercharging

their growth and leading to bigger, stronger smolts.

Proof is in the pictures – notably the well-known photos Carson Jeffres, a biologist with the University of California, Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, took in 2014 of two salmon smolts side by side.

Environmental groups are scrambling to help the fish, and while many salmon advocates call on regulators to keep more water in the Central Valley’s rivers, others are focusing their campaigning on more complex elements of the chinook’s habitat – especially floodplains.

For decades, in fact, floodplain rearing habitat was left out of the picture.

“It’s one of the missing links,” Jeffres, at UC Davis, said. “Floodplains have been this underrepresented component of the life history of the fish.”

It’s on these lowland environments

where a little water can go a long way. That’s because when a

river spills over its banks a profound ecological chain reaction

begins. Microorganisms proliferate, some feeding on sunlight

through photosynthesis, others metabolizing the carbon stored in

submerged plant debris. When small fish enter these environments,

they feast on invertebrates, growing larger and stronger than

they would if they remained in the mainstem of the river.

It’s on these lowland environments

where a little water can go a long way. That’s because when a

river spills over its banks a profound ecological chain reaction

begins. Microorganisms proliferate, some feeding on sunlight

through photosynthesis, others metabolizing the carbon stored in

submerged plant debris. When small fish enter these environments,

they feast on invertebrates, growing larger and stronger than

they would if they remained in the mainstem of the river.

“Ecosystems run on energy, that energy comes from the sun, and we need to route that sunlight into the landscape,” Katz, with California Trout, explained. Floods, he said, allow fish “to capitalize on these processes.”

‘No Extra Water Needed’

David Guy, president of the Northern California Water Association, said farmers have supported efforts to preserve fish and wildlife and have been enthusiastic about floodplain restoration as a fishery enhancement. Guy’s organization is a member of the Floodplain Forward Coalition, a Central Valley-based collective that includes farms and conservation groups that has helped coordinate floodplain-focused restoration along the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers.

“We have seen success working with these same partners for waterfowl along the Pacific Flyway and spring-run salmon in Butte Creek, both of which have benefitted from reactivating the floodplain and spreading water out and slowing it down,” Guy said.

He added that while farmers support preservation of the region’s fish and wildlife, they know “we can stretch our water across the floodplain in a way that also sustains water for farming into the future.”

One of the strongest selling points

of floodplain restoration among traditionally adversarial

stakeholders is that, in many cases, no extra water is needed.

While this isn’t everywhere true – in the San Joaquin Valley,

Rentner said, river depletion and streambed scouring means

flooding will not happen in the average year – in the Sacramento

system, it is. Here, simple restructuring of the levees lining

the valley’s rivers can revive annual flood cycles.

One of the strongest selling points

of floodplain restoration among traditionally adversarial

stakeholders is that, in many cases, no extra water is needed.

While this isn’t everywhere true – in the San Joaquin Valley,

Rentner said, river depletion and streambed scouring means

flooding will not happen in the average year – in the Sacramento

system, it is. Here, simple restructuring of the levees lining

the valley’s rivers can revive annual flood cycles.

“With a notch at Fremont Weir, all those years when we don’t get floods under current circumstances will have floods in the future,” Jeffres said, referring to the flood control gate at the upstream end of the Yolo Bypass. A little further north, the Sutter Bypass, he said, is similarly positioned to flood with relatively minor changes to the landscape.

Just as important as increasing the frequency of floods on these large bypasses is increasing their duration, Katz explains. Currently, the Yolo Bypass, which was engineered in the early 20th century, only floods during peak flow events, and by design it only retains floodwaters for a brief period. Katz hopes to see a system of berms, gates and weirs installed that will extend the duration of flood events from days to weeks on about 10,000 acres of the bypass.

The ecological benefits of floodplains go far beyond fish. Birds of many species, notably migratory waterfowl by the millions, utilize inundated floodplains, as do reptiles, amphibians and mammals large and small.

“We’re talking everything from bugs to bunnies,” said Mount, with PPIC.

After the Dos Rios Ranch floodplains near Modesto were restored, endangered riparian brush rabbits reappeared on their own.

“That was a great surprise,” said Rentner, with River Partners. “We thought we would need to reintroduce them.”

And there are still other unique benefits layered into restoration work of this kind: On some seasonally flooded land, summer farming can continue, while land that is restored to its natural state could, in some cases, be opened to public access, giving recreational value to floodplain projects. These projects also sequester planet-heating carbon from the air by restoring riparian woodlands.

“If we’re still talking about doing this in 20 years, then I’d say we missed an opportunity.”

~Tim Ramirez, Central Valley Flood Protection Board member.

Momentum is building on projects across the valley, but there is widely shared agreement that the pace of change remains too slow for projects formally embedded in state policy. Stakeholders are eager to get these projects done, but it’s not clear when the growing buzz of interest in floodplains will translate into earth-moving action on the ground.

Ramirez, at the Flood Protection Board, said many levee setback and floodplain projects now on the drawing board saw their conception with the floods of 1997. The governor’s Resilience Portfolio only came out a year ago, he points out, “and it takes a year just to write and receive a grant.”

He knows years more will pass before routine flood events are restored to vast areas of currently dry Central Valley farmland.

“But if we’re still talking about doing this in 20 years,” he said, “then I’d say we missed an opportunity.”

Alastair Bland is a freelance writer who has covered a wide range of topics including water, climate change, fisheries, marine conservation and research, and agriculture. He also curates the Foundation’s Aquafornia daily water news roundup. Please send any comments on the article to Doug Beeman, Deputy Director, News & Publications. Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.