Can a New Approach to Managing California Reservoirs Save Water and Still Protect Against Floods?

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: Pilot Projects Testing Viability of Using Improved Forecasting to Guide Reservoir Operations

Many of California’s watersheds are

notoriously flashy – swerving from below-average flows to jarring

flood conditions in quick order. The state needs all the water it

can get from storms, but current flood management guidelines are

strict and unyielding, requiring reservoirs to dump water each

winter to make space for flood flows that may not come.

Many of California’s watersheds are

notoriously flashy – swerving from below-average flows to jarring

flood conditions in quick order. The state needs all the water it

can get from storms, but current flood management guidelines are

strict and unyielding, requiring reservoirs to dump water each

winter to make space for flood flows that may not come.

However, new tools and operating methods are emerging that could lead the way to a redefined system that improves both water supply and flood protection capabilities.

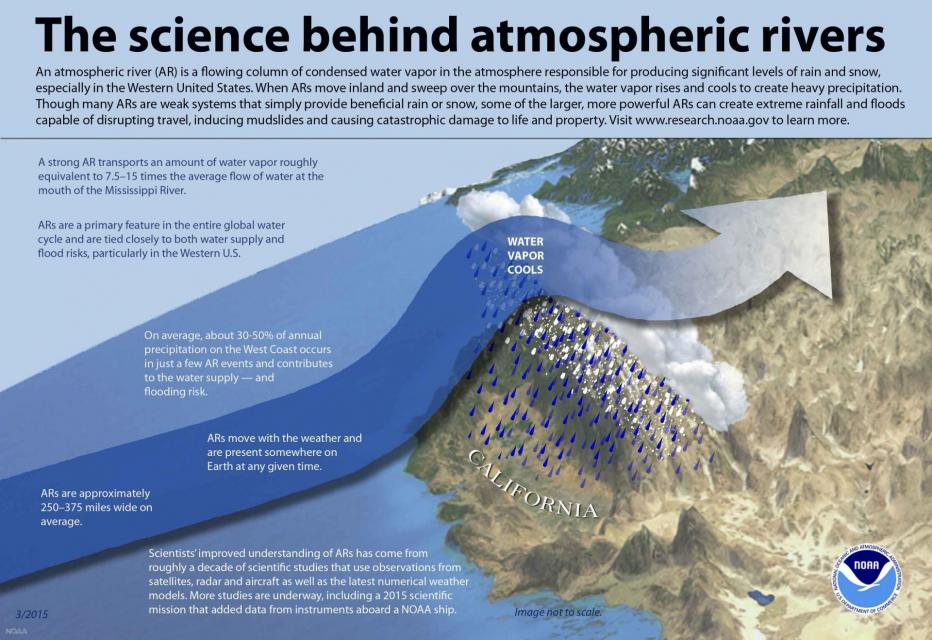

Known as Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations (FIRO), the approach centers on using the latest forecast technology to plan for the arrival of atmospheric rivers. Those are the torrents of moisture in the sky that barrel into California from the Pacific Ocean. Atmospheric rivers are critical to the state’s water supply, accounting for as much as half of its annual precipitation. But they can also cause catastrophic flooding.

FIRO’s advocates say its application is critical in a state that would do well to capture all the water it can during its short storm window.

“We have been managing our water resources the same way for the last 60 years and it’s time to change that,” said Michael McMahon, senior hydro-meteorologist with HDR Engineering in Denver, Colo. “We can improve what we already have without building anything new.”

McMahon, a consulting scientist, is working with FIRO projects at Folsom Dam, the Bureau of Reclamation facility near Sacramento, and at Lake Mendocino in Sonoma County, which is owned and operated by the Army Corps of Engineers.

FIRO is also being tested and evaluated at Prado Dam in Riverside County and in the Yuba and Feather river watersheds. Proponents say it is a valuable means to wring every available drop of water from atmospheric rivers while keeping the public safe.

“With FIRO, your water supply benefit is based on your last big storm event because at the end of the event, you are going to hold on to more water if the forecast is dry,” said Chris Delaney, senior engineer with Sonoma Water.

Flipping the Paradigm

California’s dams serve several purposes – flood control, water supply and maintaining adequate river flows for fish, wildlife and water quality. These multiple purposes often conflict as storing water or releasing it has consequences for people and the environment, especially during stormy weather.

“We have been managing our water resources the same way for the last 60 years and it’s time to change that.”

Michael McMahon, senior hydro-meteorologist with HDR Engineering

Operating rules state that reservoirs have a maximum storage level for water supply and must keep a portion of the reservoir dedicated to capturing high inflows and detaining them until high flows downstream have receded. That detention space is set at a high enough level to safely operate a project’s dam and spillway.

“With FIRO, we flip that paradigm and say we can store more water in the reservoir because we use forecasting,” Delaney said. “If we see something on the horizon, we will release water in advance so there is adequate space in the reservoir to still detain high inflows.”

Sonoma Water knows well the fickle nature of incoming storms. Several years ago, the agency released tens of thousands of acre-feet of water from Lake Mendocino in anticipation of an atmospheric river that never arrived. Dryness ensued and water supplies were tight.

Since then, advancements in understanding and forecasting atmospheric rivers have put them in a much better position to more accurately anticipate their size and timing. Applying FIRO at Lake Mendocino during the winter of 2018-2019 resulted in an additional 3,000 to 4,000 acre-feet in the lake. The water agency has permission from the Corps of Engineers to follow what’s called “a major deviation” from its established flood control operating rules for 2020, Delaney said.

The Corps, which writes the book on how federally

funded reservoirs are operated for flood management, recognizes

the benefit FIRO provides but must be absolutely sure a

reservoir’s flood risk management performance is not diminished.

The Corps, which writes the book on how federally

funded reservoirs are operated for flood management, recognizes

the benefit FIRO provides but must be absolutely sure a

reservoir’s flood risk management performance is not diminished.

Greg Kukas, chief of the hydrology and hydraulics branch for the Corps’ Sacramento District, said implementing and evaluating FIRO needs to be done on a project-specific basis because each dam has its own release and downstream flow characteristics that can limit the extent of the FIRO application.

Kukas pointed to the recently revised water control manual at Folsom Dam that provides operational flexibility to increase water storage in the spring and to reduce downstream flood risk through FIRO.

Joe Countryman, a member of the Central Valley Flood Protection Board, said FIRO’s functionality varies depending on the capacity of the river downstream of a reservoir. Oroville Dam has a large downstream capacity but is limited in how it can release water because the release gates are at the top of the reservoir, he said. In the San Joaquin River Basin, a place like New Don Pedro Reservoir has limited capacity in the downstream channel.

FIRO “is a valuable tool, but it’s not the end-all,” Countryman said.

Delaney said the goal is to permanently change the water control manual for Lake Mendocino based on the results of the next few years of research and implementation of the pilot program. Lake Mendocino operations are still in the development and evaluation phase, said Kukas, adding that Sonoma Water and the Corps are in “fine-tuning mode.”

FIRO is especially applicable in the

Yuba and Feather river systems, which have a long history of

catastrophic floods. Since 1950, five major floods have resulted

in 41 deaths and significant property damage. Curt Aikens,

general manager of Yuba Water Agency, said FIRO is “an overall

climate resiliency tool” that enables managers to get more

effective use from their reservoirs.

FIRO is especially applicable in the

Yuba and Feather river systems, which have a long history of

catastrophic floods. Since 1950, five major floods have resulted

in 41 deaths and significant property damage. Curt Aikens,

general manager of Yuba Water Agency, said FIRO is “an overall

climate resiliency tool” that enables managers to get more

effective use from their reservoirs.

“We will get a better forecast of the atmospheric rivers, which are the main cause of floods in our region,” he said. “That will give us a better forecast of runoff [and] we will be better be able to manage flood risks for our community.”

The Yuba and Feather river watersheds were slammed by an atmospheric river in 1997, putting large portions of southern Yuba County underwater after multiple levee failures. For its part, Yuba Water is guarding against a repeat through an updated water control manual that includes FIRO and a second spillway planned at New Bullards Bar Reservoir.

DeDe Cordell, communications manager for Yuba Water Agency, said engineers believe that should a 1997-sized storm return, the tools are in place to take significant pressure off the levee system and roughly double the level of flood protection.

Applying FIRO at Lake Mendocino during the winter of 2018-2019 resulted in an additional 3,000 to 4,000 acre-feet in the lake.

Meanwhile at Prado Dam in Riverside County, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography’s Center For Western Weather and Water Extremes is working with Orange County Water District and the Corps of Engineers to see the extent to which FIRO can be applied to the Santa Ana River watershed.

The downstream portion of the Santa Ana River flood control system, Prado Dam is an important water supply source for Orange County. The water district can temporarily store as much as 10,000 acre-feet of water behind the dam during the flood months between October and February and 20,000 acre-feet of water in the non-flood season. The goal is that through FIRO, 20,000 acre-feet can be stored year-round.

Accounting for Unpredictability

Flood control dams make many parts of California livable and with emerging science and technology, it appears a new way of managing reservoirs is on the horizon.

Public safety is paramount and is the reason why rule curves are aggressively conservative, said McMahon, the HDR hydro-meteorologist. He noted, however, that dams today serve many functions, including making sure minimal instream flows and cold water are available for fish.

FIRO “is a valuable tool, but it’s not the end-all.”

Joe Countryman, Central Valley Flood Protection Board

Because FIRO is based on atmospheric models built on observational data, an increase in remote sensing capabilities is needed to improve the forecasting process, McMahon said. FIRO is being tested against a broad spectrum of hydrologic scenarios that highlight how much a forecast can be wrong, said Kukas, noting that it’s crucial to understand the risks inherent in FIRO.

“The consequences can be a loss of storage by overreacting to a forecast or … not making a sufficiently large release based on a forecast that underpredicts actual runoff,” he said. “How well a given plan performs in the face of the remaining uncertainty in forecasts is a critical thing for us to understand.”

McMahon acknowledged it can take time to change people’s minds about FIRO, but he’s enthusiastic about where the effort is going.

“Are we going to be perfect right out of the gate? No,” he said. “But I guarantee beyond a shadow of a doubt we are going to get better as time goes on.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Further reading

- Western Water: Understanding Streamflow Is Vital to Water Management in California, But Gaps In Data Exist, Oct. 24, 2019

- Western Water: ‘Ridiculously Resilient Ridge,’ Climate Change and the Future of California’s Water, Feb. 9, 2018

- Western Water: Better Forecasting Is Key to Improved Drought and Flood Response, Nov. 14, 2017

- Western Water: Crisis at Oroville May Be Basis for Renewed Operations Criteria, March 27, 2017

- Aquapedia: Flood management

- Aquapedia: Atmospheric rivers