Can Steadier Releases from Glen Canyon Dam Make Colorado River ‘Buggy’ Enough for Fish and Wildlife?

WESTERN WATER Q&A: Ted Kennedy, U.S. Geological Survey aquatic scientist

Water means life for all the Grand Canyon’s inhabitants, including the many varieties of insects that are a foundation of the ecosystem’s food web. But hydropower operations upstream on the Colorado River at Glen Canyon Dam, in Northern Arizona near the Utah border, disrupt the natural pace of insect reproduction as the river rises and falls, sometimes dramatically. Eggs deposited at the river’s edge are often left high and dry and their loss directly affects available food for endangered fish such as the humpback chub.

Water means life for all the Grand Canyon’s inhabitants, including the many varieties of insects that are a foundation of the ecosystem’s food web. But hydropower operations upstream on the Colorado River at Glen Canyon Dam, in Northern Arizona near the Utah border, disrupt the natural pace of insect reproduction as the river rises and falls, sometimes dramatically. Eggs deposited at the river’s edge are often left high and dry and their loss directly affects available food for endangered fish such as the humpback chub.

Ted Kennedy, a U.S. Geological Survey aquatic biologist, led a recently concluded experimental flow that is raising optimism that the decline in insects such as midges, blackflies, mayflies and caddisflies can be reversed. Conducted under the long-term, comprehensive plan for Glen Canyon Dam management during the next 20 years, the experimental flow is expected to help determine dam operations and actions that could improve conditions and minimize adverse impacts on natural, recreational and cultural resources downstream.

Western Water spoke with Kennedy about the experiment, what he learned and where it may lead. The transcript has been lightly edited for space and clarity.

WW: What is the problem this experimental flow is addressing?

KENNEDY: We think that the dam is creating an artificial intertidal zone that runs all the way down to Lake Mead because of how canyon-bound the river is and because there’s no really large tributaries in the Grand Canyon segment. We think that the artificial intertidal zone is constraining the abundance and diversity of the invertebrate prey that’s available for fishes. We are hoping that by providing stable and low flows on weekends during periods of peak aquatic insect activity that we can increase survival of these aquatic insect eggs and then eventually get larger populations of larval and adult insects that can fuel fishes, birds and bats.

KENNEDY: We think that the dam is creating an artificial intertidal zone that runs all the way down to Lake Mead because of how canyon-bound the river is and because there’s no really large tributaries in the Grand Canyon segment. We think that the artificial intertidal zone is constraining the abundance and diversity of the invertebrate prey that’s available for fishes. We are hoping that by providing stable and low flows on weekends during periods of peak aquatic insect activity that we can increase survival of these aquatic insect eggs and then eventually get larger populations of larval and adult insects that can fuel fishes, birds and bats.

Mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies are really common insect groups that a lot of people have heard of. Well, it turns out we don’t have them in the Grand Canyon. Basically, 80 percent of aquatic insects have river-edge, egg-laying behavior. So, if you impose an artificial intertidal zone, these female insects, they don’t realize the water is going to drop out hours later; they’re just sticking their eggs right at the water’s edge.

WW: What did the river environment look like before the construction of Glen Canyon Dam?

KENNEDY: Before the dam there were much greater annual scale changes in discharge from large snowmelt flows in May and June to much lower flows than we see now in the fall. The range of annual fluctuations used to be much greater and what we have now are flows that are much more stable on an annual timescale, but over hourly timescales they are much more variable now because of [hydropower operations].

WW: What prompted the creation of the “bug flow” and how does it help with the production of the desired insects?

KENNEDY: I and other investigators had noticed the absence of mayflies and caddisflies from the Grand Canyon and were never quite sure why. These insects are used as indicators of river health in a lot of places and so people were raising the alarm, 15 to 20 years ago. But other people said it’s the fish that drive the management and we’re not sure that these insects are really limiting the fish populations. … There are two types of aquatic insects [midges and blackflies] in the Grand Canyon and these were the key prey items for fishes everywhere we looked. We went back to the managers and … got permission to go back and take another look at why we are missing mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies and why is the abundance of the insects we have so low.

… I realized that if I wanted to understand what was constraining aquatic insects, I needed to look at all the life stages [not just larval stages]. I got the idea to partner with these river rafters. I basically set them up with a simple light trap that they put out each night in camp and they catch the adult life stages of these aquatic insects.

… I realized that if I wanted to understand what was constraining aquatic insects, I needed to look at all the life stages [not just larval stages]. I got the idea to partner with these river rafters. I basically set them up with a simple light trap that they put out each night in camp and they catch the adult life stages of these aquatic insects.

It was through looking at some of these data on aquatic insect abundance of adult life stages throughout the Grand Canyon that we started seeing these links between the [hydropower operations] and the aquatic insect abundance.

“Early indications are the number of fish being caught on the weekends when these flows are low and steady seems to be significantly higher compared to prior years, when weekend flows weren’t steady.”

~USGS aquatic biologist Ted Kennedy

WW: In addition to fish, what are some of the other species that would benefit from a greater abundance of aquatic insects?

KENNEDY: Aquatic insects are the foundation of river food webs as larvae and as emergent adults they are key prey items for fish. The adults, once they emerge from the river, are key prey items for swallows, swifts, bats and all of the terrestrial wildlife that we are so used to seeing along rivers. If we can increase the abundance and diversity of aquatic insects in the Grand Canyon through this flow experiment, we expect it’s going to benefit the fish populations, but we also think it will cascade out of the river and benefit the terrestrial wildlife.

WW: The experimental flow has been occurring for a few months now. What are you seeing? Do you expect the predicted 26 percent increase in insects will happen?

KENNEDY: I’ve been out on the river four times since the experimental flow started in May and it feels really buggy out there. At a stakeholder meeting in June … one of the river guides said, “Yeah, it’s been really buggy.” We don’t have data yet from our monitoring to back that up, but anecdotally it just seems to be buggy. The other thing that we weren’t expecting is … early indications are the number of fish being caught on the weekends when these flows are low and steady seems to be significantly higher compared to prior years, when weekend flows weren’t steady. I think we will reach [the 26 percent increase] and it could be we see a greater increase than that.

WW: This is the first experiment of the Long-Term Experimental and Management Plan. What happens next?

KENNEDY: We think that if we could provide these weekend steady flows we could get a boost in midge numbers. But what we’d really like to see is if we could get some of these mayflies and stoneflies and caddisflies that are present in the tributaries, but are super rare in the mainstem. If we could get some of them colonizing the mainstem, we would have a more diverse prey base. These stoneflies and mayflies, they tend to be longer-lived, like one generation a year, so we’ve been telling managers a robust test of this policy would be three consecutive years of the flow experiment. This might take that long for the mayflies and these rarer species to respond.

KENNEDY: We think that if we could provide these weekend steady flows we could get a boost in midge numbers. But what we’d really like to see is if we could get some of these mayflies and stoneflies and caddisflies that are present in the tributaries, but are super rare in the mainstem. If we could get some of them colonizing the mainstem, we would have a more diverse prey base. These stoneflies and mayflies, they tend to be longer-lived, like one generation a year, so we’ve been telling managers a robust test of this policy would be three consecutive years of the flow experiment. This might take that long for the mayflies and these rarer species to respond.

We are hoping they’ll [the managers] agree to continue testing so that we can give these longer-lived insects a chance. The hope is that we’ve found the proverbial win-win. One estimate was that would be a hit to hydropower of around $300,000. That’s real money obviously, but there are other estimates that looked at the hydropower impacts of this experiment. They actually came up with a slightly positive number, meaning that there could be a benefit because you essentially have more water to shape the weekday hydrograph when the power is at greatest value.

Editor’s Note:

It’s unclear whether scientists like Kennedy will be able to extend their research after federal budget officials directed that hydropower funds that previously paid for such research be sent instead to the U.S. Treasury. Officials with the Bureau of Reclamation, which has funded this first year, said they are looking for other funding to continue the experimental flows research.

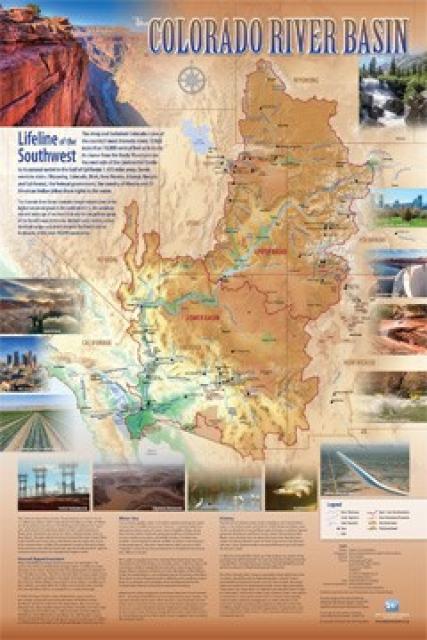

Learn more about the Colorado River

Western Water: The Colorado River: Living with Risk, Avoiding Curtailment (Fall 2017)

River Report: Conserving Species and Habitat: Five Years of the Multi-Species Conservation Program (Summer 2011)

River Report: Balancing a Complex Set of Interests: Glen Canyon Dam and Adaptive Management (Winter 2010)

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.