As Colorado River Levels Drop, Pressure Grows On Arizona To Complete A Plan For Water Shortages

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: A dispute over who speaks for Arizona has stalled work with California, Nevada on Drought Contingency Plan

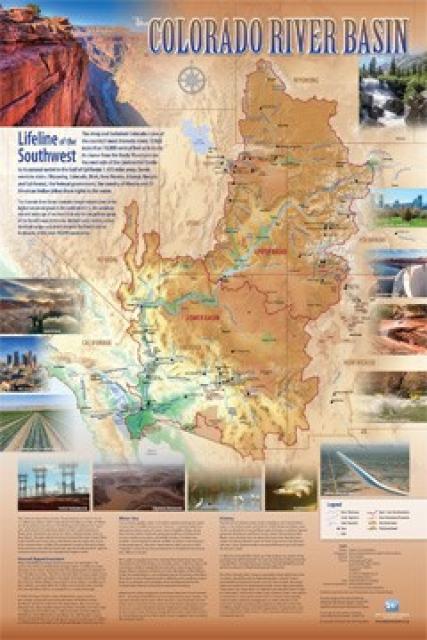

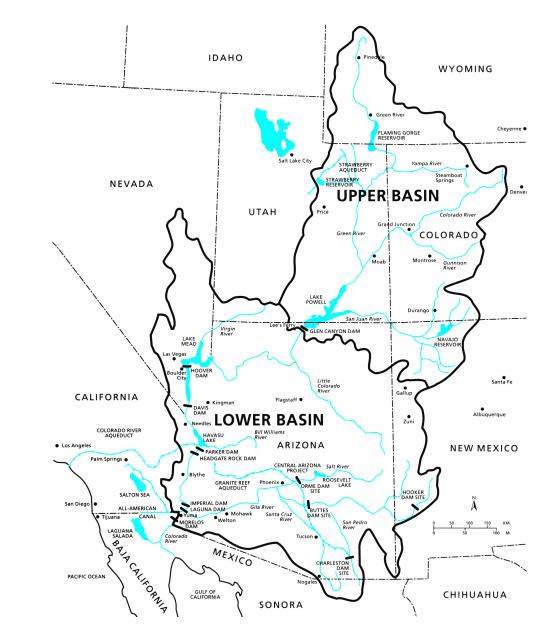

It’s high-stakes time in Arizona. The state that depends on the Colorado River to help supply its cities and farms — and is first in line to absorb a shortage — is seeking a unified plan for water supply management to join its Lower Basin neighbors, California and Nevada, in a coordinated plan to preserve water levels in Lake Mead before they run too low.

If the lake’s elevation falls below 1,075 feet above sea level, the secretary of the Interior would declare a shortage and Arizona’s deliveries of Colorado River water would be reduced by 320,000 acre-feet. Arizona says that’s enough to serve about 1 million households in one year.

The task of charting a path around shortage hasn’t been easy. The state’s main water agencies — the Central Arizona Water Conservation District (CAWCD), which runs the Central Arizona Project, and the statewide Arizona Department of Water Resources — have been unable to reach an accord regarding who should speak for Arizona before committing to a proposed Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan (DCP). Their standoff — and particularly the Central Arizona district’s management of Colorado River water — has resulted in bruised relations between Arizona and Upper Colorado River Basin states — Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming.

Still, there is an increased sense of urgency to get something done, with a record-low snowpack contributing to the driest 19-year period on record. A meager runoff this year from the Rocky Mountains into Lake Powell – the Upper Basin’s key reservoir — is expected to be 42 percent of the long-term average.

“It’s very important for us to start thinking about, what do we need to do to protect Lake Mead and to protect the water users?” Brenda Burman, commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, told the Imperial Irrigation District board May 22. “We need to be talking about what does a drought contingency plan in the Lower Basin look like? And we need action. We need action this year. If you take one message from what I’m saying today, it’s that we face an overwhelming risk on the system, and the time for action is now.”

Burman, who has repeatedly urged Basin states to act, is scheduled to speak at a June 28 briefing in Tempe, Ariz., on drought contingency plans and Arizona’s supply of Colorado River water.

“We face an overwhelming risk on the [Colorado River] system, and the time for action is now.”

~Brenda Burman, Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner

According to Reclamation, Lake Mead’s elevation is projected to range between 1,075.47 feet and 1,085.41 feet by the end of this year, with a “negligible chance” of a Lower Basin shortage condition in 2019. By 2020, the chance of a Lower Basin shortage increases significantly, along with the possibility of the lake falling to the critical elevation of 1,025 feet, the point of mandatory consultation between the Interior secretary and the Basin states to identify and implement additional measures to prop up the lake.

After being at loggerheads over the terms of an intrastate agreement, CAWCD and ADWR jointly announced May 3 that they “are committed to bringing DCP to closure in Arizona by addressing a broad range of issues that respect the concerns of all stakeholders across the state.”

Two days earlier, a statement from CAWCD pledged “to begin a fresh conversation within Arizona, including with ADWR and other stakeholders, to chart a path forward for an effective Drought Contingency Plan.”

In an interview with Western Water, Tom Buschatzke, director of ADWR, said the Drought Contingency Plan “is largely done and I believe largely agreed to by the Central Arizona Water Conservation District and certainly agreed to by the Arizona Department of Water Resources.”

But first, Arizona must reach an internal agreement on voluntary water conservation. The task has been a struggle because of the difficulty in getting all stakeholders, including CAWCD, farmers and lawmakers, to sign on to voluntary reductions.

“We have not just been able to put together a package that balances those issues … in a way that’s been acceptable to any one entity, much less the entities collectively,” Buschatzke said. “Before I can sign a DCP on behalf of the state of Arizona, I need the approval of the state Legislature and I need the support of those water users.”

The CAWCD manages and operates the Central Arizona Project (CAP), the 336-mile aqueduct that pumps Colorado River water to farmers and cities. It is responsible for the state’s repayment to the federal government for the reimbursable costs of the aqueduct’s construction.

Chuck Cullom, CAP’s Colorado River programs manager, said his agency understands the challenges posed by drought and overallocation.

“The projection from Reclamation was not a surprise and it certainly signals the need to redouble our efforts,” he said. “I appreciate Commissioner Burman’s call to action; I think that it is helpful for all the water users to heed her call and we in Arizona are working cooperatively to chart a path forward to develop an effective drought contingency plan that can be implemented in Arizona.”

Who speaks for Arizona?

The Central Arizona Water Conservation District and the Arizona Department of Water Resources approach river management through different prisms, said Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University.

“CAWCD wants to have control over its excess water. This is largely about that,” Porter said. “They want to have control over it in part because they derive funding from delivering the excess water. That funding is important to the agency because it’s their obligation to repay the financing of the CAP.”

ADWR manages water issues statewide. The two agencies were near an agreement for an intrastate drought contingency plan — dubbed DCP-plus –in 2016 that would have paved the way for the Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan, but the deal eventually collapsed. An effort to settle the matter through the state Legislature this year also collapsed.

Porter said she believes the dispute concerns which agency ultimately has responsibility to manage the state’s Colorado River allocation.

“The fight at the intrastate level is mainly over which agency has authority to approve forbearance and which Colorado River water users get to participate in forbearing,” she said. “In particular, the Gila River Indian Community, which is the largest CAP contract holder, has expressed a desire to leave water in Lake Mead. CAP has raised questions about whether a CAP contract holder should be allowed to participate because traditionally any CAP water that a user didn’t take would go into an excess pool controlled by CAP.”

Without action, ‘It’s going to be a mess.’

The idea of a Lower Basin DCP emerged five years ago as an overlay to a 2007 shortage-sharing agreement that is performing “pretty darn well,” said Terry Fulp, director of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Region. After the intense drought of the early 2000s, stakeholders had “breathed a sigh of relief” with a high flow on the river in 2011, only to be followed by the lowest consecutive years on record. Suddenly, the possibility of Lake Mead dropping to dead pool (when the water level is so low that it cannot drain by gravity through Hoover Dam’s outlets) didn’t seem far-fetched.

“The idea when we sat down in 2013 with another bad year staring us in the face was, ‘what can we do, short of renegotiating the guidelines,’” Fulp said. The idea of a DCP with Reclamation as the facilitator emerged as the answer. Fulp said the states need to complete it because waiting until the end of 2020 (when renegotiations of the 2007 guidelines must start) is too perilous.

“If we are in a bad way and crashing and then trying to renegotiate new guidelines, now you’ve really complicated it,” he said. “Now it is going to be difficult because you are trying to look to the future to put new rules in place, but your current rules aren’t working well enough to prevent a catastrophe. It’s going to be a mess.”

“If we are in a bad way and crashing and then trying to renegotiate new [shortage] guidelines, now you’ve really complicated it.”

~Terry Fulp, Regional Director, Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Region.

Managing the Colorado River’s water supply for farms and cities proceeds amid the reality that the system is overallocated, and has been from the start with the 1922 Colorado River Compact. Lake Mead receives about 9 million acre-feet of water each year, primarily from Lake Powell. However, when evaporative losses are factored in, the lake annually ends up with a structural deficit of about 1.2 million acre-feet of water.

“In years past, there was ‘extra’ water in the system to make up for the deficit,” said Porter, with Arizona State University. “Years of drought and increasing demand from other users have reduced the supply of extra water.”

Furthermore, experts in river hydrology believe water managers in the Basin must be aware of and prepared for a drier future.

Earlier this year, the Colorado River Research Group, a team of veteran university-based researchers, proposed calling the transition of the Colorado River Basin to a drier climate “aridification.” The group said the term “describes a period of transition to an increasingly water-scarce environment — an evolving new baseline around which future extreme events will occur. Aridification, not drought, is the contingency that should guide the refinement of Colorado River management practices.”

It is because of the predictions of a drier future that completion of the DCP is viewed as necessary to buttress the Lower Basin.

“DCP is important because it gives the Lower Basin states, especially Arizona, a measure of control over their destinies,” Porter said. “Rather than simply continue to withdraw water from Lake Mead until the Bureau of Reclamation declares a shortage, DCP is a vehicle for averting shortage declarations. Also, without the guidelines and DCP, any cuts would be absorbed first by the Central Arizona Project users, rather than shared.”

Getting closer to shortage conditions

Everything, of course, centers on Lake Mead, the largest man-made reservoir in the United States and the source of water for the CAP. If the lake drops below 1,075 feet elevation, the first tier of required shortages under the shortage-sharing agreement kicks in, beginning with curtailed water deliveries to some Arizona farmers.

Signed in 2007,the monumental Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead was a significant milestone for Basin users, a recognition of the need for an accelerated response to severe drought conditions. The approach — including subsequent actions for funded conservation and a binational agreement with Mexico — has resulted in hundreds of thousands of extra acre-feet of water in Lake Mead.

“Approving and fully participating in the DCP [Drought Contingency Plan] is an imperative for Arizona.”

~ Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University

Since that time, avoiding shortage has been the overriding concern in the Lower Basin with each below-average water year that has ensued. To forestall shortage, Arizona, California and Nevada have been leaving water in Lake Mead in lieu of a DCP.

“When the 2007 guidelines were finalized, the parties knew that they were going to have to renegotiate them and that’s what DCP is,” Porter said. “It’s really important for Arizona to ratify the DCP and work on ways of participating in forbearance so that we can shore up supplies in Mead and avoid a shortage declaration. The DCP is the very carefully thought-out system that the Basin states came up with for managing with shortage as the new normal.”

Chris Harris, executive director of the Colorado River Board of California, said the DCP is predicated on the belief that while the 2007 guidelines are working, “they were only taking us so far” as Lake Mead continued to drop closer to shortage conditions.

“Absent further actions, we were reaching an increased probability of hitting 1,075,” he said. “Folks said, ‘Is there anything we can do to slow that rate of descent or even bend the curve back?’”

Buschatzke, with the Arizona Department of Water Resources, said the aim is “to increase the likelihood that we could keep the lake above 1,075 through various conservation programs in which users agree not to use water.

“One of the elements of that program would be to allow tribes who have Colorado River entitlements through the CAP to do intentionally created surplus,” he said. “CAWCD does not believe those tribes have that right to do that in their own names. The state believes they have the legal right and … that is one point that we need to come to closure on and find a path forward.”

Under the terms of the 2007 agreement, so-called intentionally created surplus water is that which exists through efforts such as extraordinary conservation and system delivery improvements. Subsequent agreements with Mexico also have addressed water conservation actions that have led to significant amounts of water saved in Lake Mead.

Cullom, with the Central Arizona Project, said there has been “thoughtful disagreement” about eligibility for ICS and the accounting for stored water, but that the eligibility and ability of tribes to participate is not disputed.

“The question has been how to reconcile a number of contract issues,” he said. “CAP is supportive of tribes participating in intentionally created surplus and we are also respectful of supporting all of the contract rights and authorities for all the water users in the Colorado River Basin.”

The issue of tribal intentionally created surplus exists in the 2007 guidelines, Fulp said.

“We didn’t specifically say a tribe can do it,” he said. “What we said was anyone with a valid entitlement can do it and that includes tribes. We wrote it that way to specifically make sure the tribes were included.”

Tensions rise as water levels drop

The 1922 Colorado River Compact requires the Upper Basin states to deliver 75 million acre-feet to the Lower Basin every 10 years. The Lower Basin’s legal share is 7.5 million acre- feet a year. Balancing levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead to accomplish that during dry times is a tricky enterprise.

While Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and

Wyoming are ensuing enough water flows to meet that obligation,

CAWCD draws water from Mead to market to urban and agricultural

users. The optics of the enterprise can appear counterproductive.

While Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and

Wyoming are ensuing enough water flows to meet that obligation,

CAWCD draws water from Mead to market to urban and agricultural

users. The optics of the enterprise can appear counterproductive.

CAWCD’s seeming manipulation of its Colorado River supply sparked a furor with the Upper Colorado River Commission, which in April lamented the district’s plan to “intentionally maximize demands within the Central Arizona Project to induce larger-than-normal releases from Lake Powell,” an action that “threatens the water supply for nearly 40 million people in the United States and Mexico and threatens the interstate relationships and good will that must be maintained if we are to find and implement collaborative solutions moving forward.”

The ruckus resulted in an April 30 meeting between Arizona Department of Water Resources and the Central Arizona Water Conservation District and the Upper Colorado River Commission. Afterward, the Central Arizona district announced that “concerns from the Upper Basin Commissioners were heard and respected, and there was a productive discussion.”

Cullom, with CAP, said the dispute provides the opportunity to reinvigorate the relationship between the Upper and Lower Basins.

“The issues that were raised by the Upper Colorado River Commission point to the need for closer collaboration and for the stakeholders in the Colorado River system to get back together and work on greater transparency and also to work to develop and deliver an appropriate DCP that benefits the Upper Basin and Lower Basin,” he said. “By benefit I mean that it provides protection, resiliency and greater reliability for water users in the Basin.”

“If you hit 1,075 and anybody takes a shortage, the first red flag that ought to pop up is that the system is in trouble,”

~Chris Harris, executive director, Colorado River Board of California.

In lieu of the DCP, stakeholders could renegotiate the 2007 guidelines when they expire in 2026, though hydrologic conditions will probably dictate a greater sense of urgency before then.

“Waiting until 2026 is one option; it may not be the preferred option,” said Harris, with the Colorado River Board of California. “Based on our operating experience since 2007, we’ve recognized that implementing all these various conservation activities, including the binational programs … those things have been extraordinarily beneficial for Lake Mead. Absent those programs, we very likely would have been in a shortage as early as 2015.”

Porter, with Arizona State University, said the approaches to water management by CAWCD and ADWR are colored by their respective missions. The CAWCD “exists to deliver the water and be the steward of the Southern and Central Arizona Colorado River allocation,” she said. “There is a light in which I can see that position and say, ‘That’s pretty defensible.’ At the same time, CAWCD is a dog in the fight. It’s the Central Arizona Colorado River delivery agency. It’s not a user, but it’s more like one of the other users than the department, which is charged with Colorado River policy for the entire state.”

The Arizona Department of Water Resources has a different set of motivations, she said, with an emphasis “on continuing this very functional relationship the state has managed to establish in a very stressful time.”

A shared responsibility

Across the river from Arizona,

California holds senior water rights to the river, supplying more

than 60 percent of the water used annually by Southern

California’s cities and farms. Being in that position “is very

helpful,” said Harris with the Colorado River Board. But at the

same time, he said, users are committed to protecting Lake Mead

by storing additional water in it, if necessary.

Across the river from Arizona,

California holds senior water rights to the river, supplying more

than 60 percent of the water used annually by Southern

California’s cities and farms. Being in that position “is very

helpful,” said Harris with the Colorado River Board. But at the

same time, he said, users are committed to protecting Lake Mead

by storing additional water in it, if necessary.

“If you hit 1,075 and anybody takes a shortage, the first red flag that ought to pop up is that the system is in trouble,” he said. “If you have a couple more dry years, you could go from 1,075 down to 1,030 or even lower pretty doggone quickly. It impacts all of us in any fashion when any one of us takes a shortage, including CAP.”

While pressure for completing the DCP has increased, it remains to be seen when it reaches “done-done,” Fulp’s shorthand for something that is “signed, sealed, delivered and contractual.”

Until then, Porter said she believes the existing actions by stakeholders to keep water in Lake Mead lay the groundwork for finalizing intrastate and interstate agreements while averting any crisis.

“If we can continue to negotiate while also continuing to leave the amounts of water in Lake Mead that we would under DCP, we are not under the kind of pressure that we would probably need to be to get to a solution in a month,” she said.

It’s also important to recognize the shared responsibility the seven states bear for protecting and preserving Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

“If you look back, you can see that for at least 20 years, maybe longer, the Colorado River Compact states have really done well and we who live in communities that rely in whole or in part on Colorado River water have all benefited from these very functional relationships,” Porter said.

Stakeholders don’t have much time to reach agreement on the DCP. “As the reservoirs continue to drop, finalizing the DCP is becoming increasingly more important,” said Bill Hasencamp, Colorado River program manager with the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. “Having the DCP in place, which would be in effect through 2026, would provide short-term stability so that water users can then focus on the long-term challenges facing the Colorado River.”

To learn more about the Colorado River and drought, explore these additional readings:

- River Report: A Warmer Future and Increased Risk

- River Report: Keeping System Conservation Going on the Colorado River

- River Report: Bending the Curve: The Lower Basin Drought Contingency Proposal

- Aquapedia: Colorado River

- Aquapedia: Colorado River Timeline

- Aquapedia: Colorado River Seven States Agreement

In the meantime, people from both basins will continue to seek an approach that protects Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

“We need to strengthen that communication, particularly when the system is under stress because of poor hydrology,” CAP’s Cullom said. “Our messaging was insensitive to issues in the Upper Basin. The Upper Basin reminded us about the need for broader communication and dialogue, and I think we have been responsive to that reminder.”

Harris with the Colorado River Board likened the situation to the early 2000s, when pressure mounted for California to scale back its take of Colorado River water to its basic mainstream entitlement of 4.4 million acre-feet. The result was the landmark 2003 Quantification Settlement Agreement that featured the largest-ever farm-to-urban water transfer between the Imperial Irrigation District and San Diego.

“I look at where we are right now, and I don’t think it’s as complicated as where we were then,” Harris said. “That was an enormous and monumental challenge for California to get itself back in line and back to its basic mainstream apportionment.”

Furthermore, Harris said that failing to complete the DCP would mean “squandering an enormous opportunity in our collaborative relationship with Mexico,” because the Binational Water Scarcity Contingency Plan, which includes Mexican provisions to protect and boost Lake Mead elevations, “is solely contingent” upon the Lower Basin states finalizing and implementing the DCP.

Porter said the issues between CAWCD and ADWR are not insurmountable.

“I think this is politics, sort of loosely termed,” she said. “I really do think that you can look at the positions of each of these agencies and their leaders and understand where they’re coming from. But at the same time, approving and fully participating in the DCP is an imperative for Arizona.”