As Deadline Looms for California’s Badly Overdrafted Groundwater Basins, Kern County Seeks a Balance to Keep Farms Thriving

WESTERN WATER SPOTLIGHT: Sustainability plans required by the state’s groundwater law could cap Kern County pumping, alter what's grown and how land is used

Groundwater helped make Kern County

the king of California agricultural production, with a $7 billion

annual array of crops that help feed the nation. That success has

come at a price, however. Decades of unchecked groundwater

pumping in the county and elsewhere across the state have left

some aquifers severely depleted. Now, the county’s water managers

have less than a year left to devise a plan that manages and

protects groundwater for the long term, yet ensures that Kern

County’s economy can continue to thrive, even with less water.

Groundwater helped make Kern County

the king of California agricultural production, with a $7 billion

annual array of crops that help feed the nation. That success has

come at a price, however. Decades of unchecked groundwater

pumping in the county and elsewhere across the state have left

some aquifers severely depleted. Now, the county’s water managers

have less than a year left to devise a plan that manages and

protects groundwater for the long term, yet ensures that Kern

County’s economy can continue to thrive, even with less water.

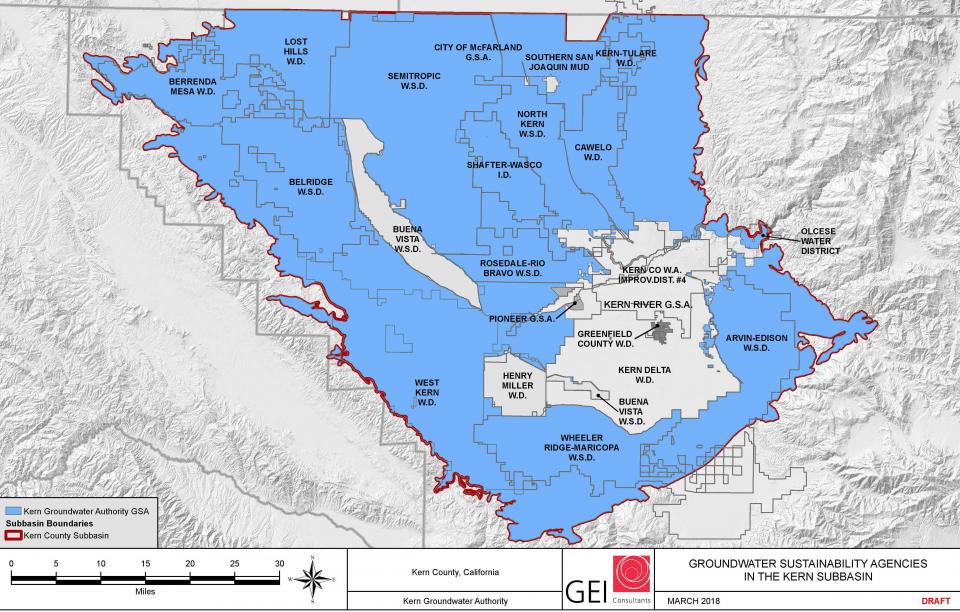

Exactly how sustainability will be achieved under the state’s 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) is still to be determined. The Kern Groundwater Authority, formed in the wake of SGMA, is drafting a plan for much of the Kern subbasin, hiring consultants to model scenarios and holding stakeholder meetings to educate people about what’s ahead. Members of the authority’s board have listened to ideas such as groundwater transfers from within the basin that might help blunt the economic impacts from meeting SGMA’s requirements.

Whatever plan is developed, the impact is likely to be significant: As much as 185,000 acres of Kern County crop land — roughly 20 percent of the county’s irrigated farm acreage — could be taken out of production to meet sustainable groundwater use requirements, according to a report by Alliance Ag Services, a brokerage and consulting firm in Bakersfield.

“Unfortunately, there are still a number of farmers who don’t have a very good understanding of it.”

~Jason Selvidge, a farmer and board member of the Kern Groundwater Authority.

“I haven’t heard an estimate yet that I thought was too high for the amount of land going out of production,” said Jason Selvidge, a farmer and board member of the Kern Groundwater Authority, the Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) covering a large portion of the Kern subbasin. “I think it’s a big number.”

Situated at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley in the shadow of the southern Sierra Nevada and with Bakersfield as its anchor, Kern County is the top agricultural producer in the nation, with grapes, almonds and citrus leading the way. One in five jobs is directly or indirectly linked to the agricultural industry and five of the top 15 private employers in the county are agriculture-based, according to the Kern County Farm Bureau and the Kern Economic Development Corporation.

SGMA will impact those figures. Despite being signed into law more than four years ago, the weight of the Act is beginning to be felt. Pumping restrictions will affect farm revenue, taxes and jobs.

‘A Big Train Coming’

Farmers for the most part have absorbed cuts in water deliveries though smarter water use, but efficiency only goes so far before land must be fallowed, said Selvidge, who serves as vice president of the Rosedale-Rio Bravo Water Storage District, west of Bakersfield. In his case, that means moving away from lesser-value row crops such as corn and alfalfa.

Kern is among 21 critically overdrafted basins statewide that are rapidly approaching a January 2020 deadline to submit groundwater management plans to the state of California under SGMA with a goal of achieving sustainability by 2040.

“Unfortunately, there are still a

number of farmers who don’t have a very good understanding of

it,” said Selvidge. He and his fellow board members at the Kern

Groundwater Authority are making landowners and neighboring

districts aware of what to expect.

“Unfortunately, there are still a

number of farmers who don’t have a very good understanding of

it,” said Selvidge. He and his fellow board members at the Kern

Groundwater Authority are making landowners and neighboring

districts aware of what to expect.

“The ones that are out front have had some understanding for a couple of years now, but no one really knew how it was going to shape up,” he said. “They just knew there’s a big train coming down the track.”

Christina Babbitt, who manages the California Groundwater Program at Environmental Defense Fund, acknowledged SGMA is likely to change how land is used, and that will affect rural economies.

“We recognize SGMA could be a very big lift for many agricultural users and we need to think of ways to help soften the landing in these areas,” she said. Incentive-based strategies such as water trading may help soften the blow, Babbitt added. She praised efforts in Kern County to devise a workable sustainability plan.

“There is a lot of speculation as to what’s going to happen in Kern County,” she said. “I really admire the leadership there to try to do what they need to do to get their plan accepted.”

After a long history of treating groundwater as a virtually unregulated resource, California in 2014 became the last Western state to regulate groundwater through SGMA, a bottom-up approach that requires local groundwater agencies like Kern to show how they will sustainably pump groundwater by 2040.

The Kern Groundwater Authority is comprised of 16 public agencies, 14 of which are water districts. Each authority member is crafting its own approach to achieving sustainability as part of the larger plan that will be submitted to the state. The authority also is charged with ensuring coordination with other adjacent groundwater sustainability agencies. Each district has different water sources it will build from and officials will work with landowners to consider their fee structures for groundwater pumping. Some members of the Kern Groundwater Authority are not developing their own chapter for the Groundwater Sustainability Plan, instead participating in the chapter developed by a neighboring agency within the authority’s jurisdiction.

There have been challenges. The Kern County Board of Supervisors decided last year that the county would not be a part of the Kern Groundwater Authority, saying it didn’t want to assume managerial responsibility — or the liability — for the acreage outside the jurisdiction of other water districts. Authority members fear the county’s action may cause the Kern Basin, the largest in the state, to be designated probationary, which would have a significant impact.

Still, the authority expects to have a draft of its sustainability plan ready for public review by this August.

Striking a Balance

The 20-year path to sustainability will be an iterative process, said Jon Reiter, chief executive officer of Maricopa Orchards, a leading almond, pistachio and fresh produce grower in Kern County.

“There is going to be a portion of the initial [plans] that are going to say, ‘Look, we have 20 years to establish a path to sustainability and we intend to implement certain things,’” he said. “Maybe we are going to have an allocation of groundwater credits, we might have fees we are going to charge on pumping. We may have marketable credits. While that may be contemplated for the future, I don’t see a lot of it being implemented yet.”

Eric Averett, general manager of the

Rosedale-Rio Bravo Water Storage District (part of the Kern

Groundwater Authority), likened the process to what people

regularly experience with their household finances as they try to

balance income and expenses.

Eric Averett, general manager of the

Rosedale-Rio Bravo Water Storage District (part of the Kern

Groundwater Authority), likened the process to what people

regularly experience with their household finances as they try to

balance income and expenses.

“I think most entities within the basin have a really good feel for what their water budget is,” he said. “The hard part is yet to come, which is, how do you balance it?”

Formed 60 years ago as a groundwater recharge project, Rosedale-Rio Bravo, which receives water from the Central Valley Project, the State Water Project and the Kern River, makes few direct deliveries to customers. Rosedale replenishes groundwater mostly with imported supplies, which has helped keep its groundwater in balance for more than 25 years, Averett said.

A big piece of the SGMA equation is establishing a regime under which growers manage the water beneath their feet. In Averett’s district, that means assigning water use on an individual basis.

“Each parcel will have a water budget and we will provide information to the landowner so they can manage that budget,” he said. “The parcel is the bank account and we are the generous uncle who makes the deposit into the account and the uncle who looks at the account to make sure it never goes upside down.”

“SGMA is creating some challenges, but it is also creating some opportunities and those who see the future are going to be well-poised to manage through it.”

~Jon Reiter, CEO of Maricopa Orchards, a leading almond, pistachio and fresh produce grower in Kern County.

Planning a water budget means incorporating a degree of adaptability and being ready for the inevitable periods of drought and wet years, said Selvidge, with the groundwater authority. The idea, he added, is to look at the long-term history of the basin, not what happened last year.

Living Beyond Our Means

Groundwater accounts for about 40 percent of all the water consumed in California in average years, and far more in drought years. Unlike surface water, which requires a permit to divert and use, landowners are allowed to pump as much groundwater as necessary, as long as it’s put to beneficial use.

Overdrafting an aquifer – pumping more than is naturally replenished – has caused subsidence in many parts of the San Joaquin Valley, irreversibly in some spots. Landowners said they had no choice but to pump to stay in business, but lawmakers ultimately stepped in.

According to Public Policy Institute of California’s 2019 report, Water and the Future of the San Joaquin Valley, the valley’s rate of overdraft has averaged about 2 million acre-feet each year for the past 30 years — or enough annually to fill San Luis Reservoir near Los Banos. Ending that overdraft could require taking at least 500,000 acres of irrigated cropland across the valley out of production.

“The valley is at a pivotal moment,” Ellen Hanak, director of PPIC’s Water Policy Center, said at a Feb. 22 conference in Fresno. “This is a region that faces unprecedented challenges and inevitable change.”

“We recognize SGMA could be a very big lift for many agricultural users and we need to think of ways to help soften the landing in these areas.”

~Christina Babbitt, senior manager, Environmental Defense Fund’s California Groundwater Program.

Reversing that overdraft is at the heart of the groundwater sustainability plans that each groundwater sustainability agency in California must prepare. Some of the plans will be “more aspirational than practical, but that’s OK,” Erik Ekdahl, deputy director with the State Water Resources Control Board, said at the Association of California Water Agencies’ legislative forum March 6 in Sacramento.

The State Water Board will consult with the California Department of Water Resources on the validity of sustainability plans, a process that includes ensuring that basins with multiple plans have a coordination agreement between all the participants.

“The plans have to work together and essentially function as one plan for the basin,” said Sam Boland-Brien, manager of the State Water Board’s Groundwater Management Program. And ideally, the plans will be comprehensive enough to avoid state intervention.

“We want the problem solved and we obviously prefer [local officials] to succeed,” Boland-Brien said, but “we are ready to step in if we have to.”

Challenges and Opportunities

Like all growers, Maricopa Orchards’

Reiter decides on planted acreage depending on various

circumstances, such as market conditions. “We take great efforts

to not over plant,” he said. “Every tree we put into the ground,

we look at where is that water coming from 10 years from now when

that tree is mature.”

Like all growers, Maricopa Orchards’

Reiter decides on planted acreage depending on various

circumstances, such as market conditions. “We take great efforts

to not over plant,” he said. “Every tree we put into the ground,

we look at where is that water coming from 10 years from now when

that tree is mature.”

With groundwater pumping likely to be limited at some point, Reiter has worked out deals for solar energy production on some of his land to gain an economic use that’s not reliant on water. That also allows him to shift the groundwater and surface water associated with that land to other planted acreage.

Reiter believes the implementation of SGMA plans is the beginning and not the end of the process.

“SGMA is creating some challenges, but it is also creating some opportunities and those who see the future are going to be well-poised to manage through it,” he said. “We are in the transition mode, we are not in the transformation mode yet.”

Options For Achieving Groundwater Sustainability

Agencies within the Kern Groundwater Authority are considering a variety of options as they develop plans to bring groundwater basins into balance. Among the possible components are:

- Groundwater transfers/credits

- Parcel-based water budgets

- Supply augmentation

- Land fallowing

- District-owned recharge

- Private recharge via dedicated recharge basins, on-field recharge or recharge using subsurface systems

- Addressing low groundwater ‘hot spots’ within the subbasin

- Pumping limits or surcharges for exceeding limits, with surcharge funds invested in projects to improve groundwater levels

- In-lieu programs to encourage use of available surface water rather than groundwater

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Further Reading

- Western Water: California Leans Heavily on its Groundwater, But Will a Court Decision Tip the Scales Against More Pumping? Oct. 19, 2018

- Western Water: Could the Arizona Desert Offer California and the West a Guide to Solving Groundwater Problems? May 18, 2018

- Western Water: Novel Effort to Aid Groundwater on California’s Central Coast Could Help Other Depleted Basins, May 4, 2018

- Western Water: How San Joaquin Valley Growers are Helping to Address Land Subsidence, Sept. 6, 2017

- Western Water: Groundwater is the ‘neglected child’ of the water world, these authors say, Aug. 29, 2017

- Western Water: Now Comes the Hard Part: Building Sustainable Groundwater Management in California, Summer 2017

- The 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act: A Handbook to Understanding and Implementing the Law

- Aquapedia: Sustainable Groundwater Management Act