Is Ecosystem Change in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Outpacing the Ability of Science to Keep Up?

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: Science panel argues for a new approach to make research nimbler and more forward-looking to improve management in the ailing Delta

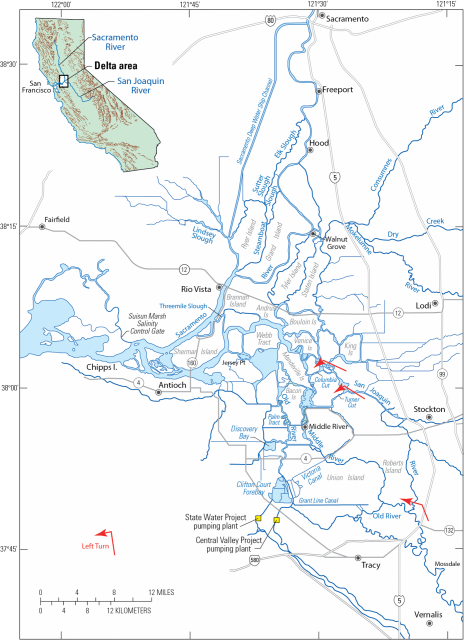

Radically transformed from its ancient origin as a vast tidal-influenced freshwater marsh, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta ecosystem is in constant flux, influenced by factors within the estuary itself and the massive watersheds that drain though it into the Pacific Ocean.

Radically transformed from its ancient origin as a vast tidal-influenced freshwater marsh, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta ecosystem is in constant flux, influenced by factors within the estuary itself and the massive watersheds that drain though it into the Pacific Ocean.

Lately, however, scientists say the rate of change has kicked into overdrive, fueled in part by climate change, and is limiting the ability of science and Delta water managers to keep up. The rapid pace of upheaval demands a new way of conducting science and managing water in the troubled estuary.

There is much at stake. Never static, the Delta is central to California’s water conveyance system. For decades, stakeholders have wrangled about the best way to manage it for water supply reliability and ecosystem protection. Rapid change adds another layer of complexity to that problem.

“This is a big issue,” said Jeff Mount, senior fellow with the Public Policy Institute of California. “It’s all changing so rapidly that our traditional approach to scientific inquiry [observation, hypothesis, testing and theory] is being outstripped by the pace of change. It’s damn difficult and it’s made worse by the fact that we are in this increasing volatility.”

“The accelerating speed of change means that ecological systems may not hold still long enough for scientists to understand them, much less use their findings to inform management.”

~Report: Preparing for a Fast-forward Future in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

The Delta is the source of drinking water for 29 million Californians from the San Francisco Bay Area to San Diego and irrigation for 3 million acres of farmland that help feed the nation. But the ecosystem challenges in the Delta itself are daunting – invasive aquatic species, more frequent toxic algal blooms, bare minimum stocks of native fish, warming air temperatures, sea-level rise that could imperil levees and seasonal precipitation that swings sharply from drought to flood and back to drought. These challenges frustrate water supply management and attempts to “fix” the health of the West Coast’s largest freshwater tidal estuary.

Declining estuary health could impair the ability of the State Water Project and federal Central Valley Project to pull water with their massive pumps from the south end of the Delta and send it to cities and farms across a wide area of central and Southern California. Science underpins decisions about water management and ecosystem protection. There is also the need to acknowledge the Delta’s sense of place and unique cultural value.

Challenging Assumptions

The tensions surrounding whether science and management can keep pace with the changes in the Delta were highlighted in a paper prepared by the Delta Independent Science Board, which evaluates science programs that support adaptive management of the Delta. The paper has been submitted for publication in the journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science.

The tensions surrounding whether science and management can keep pace with the changes in the Delta were highlighted in a paper prepared by the Delta Independent Science Board, which evaluates science programs that support adaptive management of the Delta. The paper has been submitted for publication in the journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science.

The Science Board’s paper, Preparing for a Fast-forward Future in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, argues that climate change is pushing rapid environmental change, with droughts, heat waves, forest fires and floods becoming more frequent and more extreme.

“The accelerating speed of change means that ecological systems may not hold still long enough for scientists to understand them, much less use their findings to inform management,” the report says. “Faced with these challenges, science and management must adapt and change, anticipating what the systems may be like in the future.”

As a result, a business-as-usual approach will not be appropriate.

“We cannot assume that traditional management approaches will be sufficient to deal with the surprises that lie in store,” the paper says. “The need for strategic initiatives is urgent. Without a concerted effort, science and management may be overtaken by the rapidity of changes and find themselves constantly reacting rather than getting ahead of the changes.”

Key Findings: Preparing for a Fast-forward Future in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

The paper is framed around the ideas of how the Delta responds to rapid changes, or “disturbances,” and the effects on species. It challenges assumptions surrounding the study of a natural environment that is simply “out there” and unchanging, said former Science Board member Richard Norgaard, professor emeritus with the Energy and Resources Group at the University of California, Berkeley.

With human influence such a dominant force on the climate and environment, a revised approach is necessary, the scientists argue.

“We need to reorient our thinking to a changing future,” Norgaard said. “If we continue with old expectations about the world and try to act on and achieve old goals, we are going to be even less effective under more rapid change than we have to date.”

Those with a stake in the Delta say a shift in focus is needed with the aim of learning about ecosystem change to enable a more agile response.

“As conditions become more complex, if we can’t be reactive to what we are learning every year and if we are not setting up our research to learn … then we are not going to be taking advantage of the hundreds of millions of dollars we spend every year in the Delta on research and the needs to manage for species and water supply,” said Jennifer Pierre, general manager of the State Water Contractors, a group of 27 public agencies that receive water from the State Water Project, including those in Southern California.

“As conditions become more complex, if we can’t be reactive to what we are learning every year and if we are not setting up our research to learn … then we are not going to be taking advantage of the hundreds of millions of dollars we spend every year in the Delta on research and the needs to manage for species and water supply,” said Jennifer Pierre, general manager of the State Water Contractors, a group of 27 public agencies that receive water from the State Water Project, including those in Southern California.

Those living and working in the Delta say they see ample evidence that conditions are evolving quickly. Invasive aquatic vegetation is spreading rapidly and harmful algal blooms are “off the charts,” said Erik Vink, executive director of the Delta Protection Commission, a state agency charged with protecting the Delta’s natural and economic values. This year, Vink said, the downtown Stockton waterfront received danger warnings from state water quality regulators because of the appearance in three different areas of algal blooms that state regulators say had higher levels of toxins than in past years.

Vink credited the Science Board’s recognition that people’s actions are an important aspect of the Delta ecosystem equation. The paper notes how changes in the Delta have been human-driven for more than a century and that the state has long tried to resolve Delta problems through natural-science analysis and remedies, while giving less emphasis to systematically addressing the human drivers of Delta problems.

Consequences of Accelerating Change

Conditions in the Delta change daily, affected by numerous factors inside and outside the region. The Delta drains the Sacramento and San Joaquin river watersheds and upstream diversions affect water quality and other factors. The health of the ecosystem is dogged by multiple stressors, among them changing water use, changing water quality and invasive species.

Conditions in the Delta change daily, affected by numerous factors inside and outside the region. The Delta drains the Sacramento and San Joaquin river watersheds and upstream diversions affect water quality and other factors. The health of the ecosystem is dogged by multiple stressors, among them changing water use, changing water quality and invasive species.

According to the Science Board, what’s not widely appreciated are the consequences of the accelerating speed of change, of more frequent and larger extreme weather events, and of increasing encounters with tipping points.

Tipping points, such as the decline of pelagic (open water) fish such as Delta smelt, longfin smelt and threadfin shad, show a system blinking red.

“Any observer, any fisherman, anyone who lives in the Delta or anyone who has studied it will tell you there is an accelerated ecological timescale that is swirling now into an ecological crisis,” said Jay Ziegler, director of external affairs and policy with The Nature Conservancy.

Harmful algal blooms highlight the Delta recent troubles, Ziegler said, noting “they are literally strangling the Delta and deoxygenating freshwater systems.”

“We are doing a lot of really great science as we adapt to the changing conditions. And while it’s hard to keep up, we are moving faster every day.”

~Rosemary Hartman, California Department of Water Resources

Rosemary Hartman, environmental program manager with the California Department of Water Resources, said the pace of environmental change makes it more difficult to understand the already complex Delta ecosystem.

“In many cases we are transitioning from basic status-and-trends monitoring to more targeting research to answer specific questions related to rapid change,” she said.

Those questions include how endangered Delta smelt respond to warmer temperatures and how the expansion of invasive weeds is affecting the ecosystem.

The Delta has been taken over by invasive aquatic vegetation during the past 30 years, according to Hartman. The area of submersed vegetation doubled between 2005 and 2015, she said, taking up more than 30 percent of the area of all waterways. Floating vegetation (chiefly water hyacinth and water primrose) has also expanded in recent years.

The weeds provide habitat for invasive predatory fish, such as largemouth bass, and get caught in boat propellers and water facility intakes. They also create more habitat for mosquitoes that spread diseases such as West Nile virus, Hartman said.

Nimbler Water Management?

Scientists adhere to a methodical process for conducting research. But that process has been upended in the Delta by extreme events such as the 2012 to 2016 drought, marked by hot temperatures and the driest three-year period ever recorded. The drought’s effects in the Delta were sweeping — rising salinity, stress to native fish populations, and a growing abundance and distribution of invasive aquatic plants.

Scientists adhere to a methodical process for conducting research. But that process has been upended in the Delta by extreme events such as the 2012 to 2016 drought, marked by hot temperatures and the driest three-year period ever recorded. The drought’s effects in the Delta were sweeping — rising salinity, stress to native fish populations, and a growing abundance and distribution of invasive aquatic plants.

The drought of 2012 to 2016 was followed by record rainfall in 2017, then by alternating dry, wet and dry years.

“It’s a precipitation whiplash, which adds to all the complexity of trying to understand this,” said Mount, with the PPIC. “It takes years to understand it and by that time, conditions may have changed. Therein lies a really significant problem.”

Ziegler said the drought “brought all of this to our doorstep in a way that is no longer avoidable.” He noted how managers took the extraordinary step of transporting hatchery-raised fish to release near Suisun Marsh, at the Delta’s edge, because temperatures in rivers upstream of the Delta where they normally migrate from were too warm for the smolts.

“Any observer, any fisherman, anyone who lives in the Delta or anyone who has studied it will tell you there is an accelerated ecological timescale that is swirling now into an ecological crisis.”

~Jay Ziegler, director of external affairs and policy with The Nature Conservancy

People look to science to help bridge the gap between knowledge and action. The buzzword is adaptive management – changing responses as conditions change. It’s touted by many as a remedy but is sometimes hard to define and implement.

“Adaptive management can be a good thing to the extent that it works both ways and we have the science that enables it,” said Chris Scheuring, managing counsel with the California Farm Bureau Federation. “If we invest in the science to keep pace with rapid change, that could present us with opportunities to be nimbler in water management so we can deconflict species needs and human needs.”

What’s needed, said Michael George, Delta Watermaster, is forward-looking science. “What is the Delta going to be like as a result of climate change and what are we going to want to know in 20 years to plan for the long-term health of this estuary?” he said. “We’ve got to organize the science to inform decisions that allow us to understand and then test hypotheses about what the tradeoffs are.”

Moving Beyond ‘Crime Scene Science’

Achieving water quality standards and effective fish protection in the Delta while allowing for steady water exports for farms and cities is a perpetual challenge that defies ready-made solutions. State water quality plans for the Delta have been regularly delayed and heavily litigated. Negotiations have stalled over voluntary agreements – championed as a more versatile option rather than having strict state-imposed regulatory flows that would significantly cut water from Delta tributaries to farms and cities. Meanwhile, the clash between the state and federal governments continues regarding the validity of biological opinions assessing potential fishery impacts from the Central Valley Project and State Water Project.

Achieving water quality standards and effective fish protection in the Delta while allowing for steady water exports for farms and cities is a perpetual challenge that defies ready-made solutions. State water quality plans for the Delta have been regularly delayed and heavily litigated. Negotiations have stalled over voluntary agreements – championed as a more versatile option rather than having strict state-imposed regulatory flows that would significantly cut water from Delta tributaries to farms and cities. Meanwhile, the clash between the state and federal governments continues regarding the validity of biological opinions assessing potential fishery impacts from the Central Valley Project and State Water Project.

Throughout the struggle there has been a mighty effort to accurately measure and describe Delta conditions at any given time. With rapid change, formulating the right response requires collaboration and a willingness to break free of silos, said Susan Tatayon, chair of the Delta Stewardship Council.

“Whether we’re talking about biological opinions, the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan, or incidental take permits, we’ve got to move beyond institutional rigidity and muster the courage to create the conditions that allow us to experiment with new tools and technologies,” she said.

Mount with the PPIC pointed to the beleaguered Delta smelt, the tiny fish native to the region that is emblematic of the struggle to manage water in the Delta. Despite extraordinary efforts, the endangered smelt edges closer to extinction. Surveying efforts found no smelt in 2018 and 2019.

“Each time we think we understand them better, they get fewer and fewer,” Mount said.

“Each time we think we understand them better, they get fewer and fewer,” Mount said.

The Delta, he said, is a place of “crime scene” science, a process that looks at the causes and effects of undesirable outcomes in a post-mortem manner. “We don’t spend a lot of time trying to prevent the next crime.”

This happens because investment in Delta science is driven largely by the web of water quality and species management rules that dominate management of the Delta and its watershed. The Endangered Species Act, Mount said, “is our emergency room, consuming all of the light, all of the money and all of the time.”

Ziegler said the Independent Science Board’s paper raises critical questions about the Delta’s ecological conditions and whether institutions such as the Delta Science Program are geared to tackle the changing Delta environment. Created as part of sweeping Delta reform legislation in 2009, the Delta Science Program was created to provide unbiased scientific information to support water and environmental management in the Delta.

“We need to take a hard look at whether [Delta scientists] have the capacity they need and to rethink how that science is applied in governance of the Delta,” Ziegler said. “In designing the science process, we need to make sure that science is actionable – both when the system is stressed and in big water years.”

In an August briefing paper, “Building an Effective Delta Science Enterprise,” the Delta Stewardship Council noted that science in the Delta is “vigorous and fragmented,” with much of the work funded to serve specific management domains.

“The absence of an overall governance mechanism to draw together the various programs and fill gaps has brought various challenges, which hinder the Bay-Delta science enterprise and make it less efficient and less able to decisively address the system’s hardest problems,” the paper said.

Responding to Rapid Change

The Delta ecosystem has been under the microscope for generations and the amount of data gathered and applied to its management is substantial. However, a long-standing problem is that much of the science is done independently and sometimes in a one-off manner that is often driven by budgeting and regulatory compliance among water users, said George, the Delta Watermaster, whose duties include overseeing water rights among in-Delta water users.

The Delta ecosystem has been under the microscope for generations and the amount of data gathered and applied to its management is substantial. However, a long-standing problem is that much of the science is done independently and sometimes in a one-off manner that is often driven by budgeting and regulatory compliance among water users, said George, the Delta Watermaster, whose duties include overseeing water rights among in-Delta water users.

Furthermore, while there is a substantial amount of Delta research done by water users, academics and nongovernmental organizations, it is not collected, synthesized and housed in one place. To what extent the Delta Science Program becomes a hub for that information remains to be seen.

Pierre, with the State Water Contractors, said Delta science has to frame what the necessary Delta management questions are and what studies can help inform those questions. The existing approach to science, she said, tends to pile up data without providing an overall estimation of whether changes in water management are helping the Delta’s ecosystem.

Mount said a course of what he called “preemptive ecology” is needed, anticipating future conditions and acting upon them instead of pursuing the status quo.

“We have got to scramble now and start identifying strongholds – areas that species can persist in under a changing climate,” Mount said. An example of that, he said, can be seen with the efforts to reestablish endangered winter-run chinook salmon into Battle Creek, a tributary of the Sacramento River in Shasta and Tehama counties about 200 miles upstream of the Delta. The ongoing project, steered by federal and state resource agencies and the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, aims to restore about 42 miles of prime salmon and steelhead habitat on Battle Creek, plus an additional six miles on its tributaries.

Adjusting to a New Reality

The Delta will be the hub of California’s water supply for the foreseeable future. The conflict about its management will continue as will the ambiguity about proceeding even as conditions rapidly change.

“There is currently a lot of uncertainty as to how to protect, conserve and enhance the environment while also providing a clean and reliable water supply,” said Roger Patterson, who oversees strategic water initiatives in the Delta for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. The agency bought all or some of five Delta islands in 2016 with an eye toward restoring habitat and improving water supply reliability. Patterson added that water managers “should probably concentrate on the immediate need to address our already identifiable challenges, while also trying to develop contingency plans … that could be implemented if and when needed in the future.”

“There is currently a lot of uncertainty as to how to protect, conserve and enhance the environment while also providing a clean and reliable water supply,” said Roger Patterson, who oversees strategic water initiatives in the Delta for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. The agency bought all or some of five Delta islands in 2016 with an eye toward restoring habitat and improving water supply reliability. Patterson added that water managers “should probably concentrate on the immediate need to address our already identifiable challenges, while also trying to develop contingency plans … that could be implemented if and when needed in the future.”

Communicating the complexities of Delta science to the public must change as new information arrives. Scientists need to help the public understand what’s changing and why, said Norgaard with UC Berkeley. “The public is not going to adjust themselves; they are going to need signals from the scientists as to what’s happening.”

That could mean rethinking invasive species.

“The term implies the species does not belong in that ecosystem,” Norgaard said. “But with rapid change, species need to move if they can in order to survive. So, if we fight every new species that arrives in the Delta, we will in some cases be reducing that species chances of surviving.”

Norgaard noted that some invasive species will still not be welcomed, such as the nutria, a burrowing South American rodent that can damage levees and is the focus of intense eradication efforts. But, he added, “we might consider helping some species that are coming to the Delta, and we might assist existing species to move somewhere more suitable.”

Norgaard noted that some invasive species will still not be welcomed, such as the nutria, a burrowing South American rodent that can damage levees and is the focus of intense eradication efforts. But, he added, “we might consider helping some species that are coming to the Delta, and we might assist existing species to move somewhere more suitable.”

A modified approach demands a sound scientific foundation.

Part of that means putting scientific inquiry into perspective. “An issue that bedevils us is how to synthesize all of this in a way that’s helpful to understanding what’s going on,” said George, the Delta Watermaster. “How do you understand the forest when every study looks at the trees?”

State government is tackling rapid ecological change through efforts such as the Natural Resources Agency’s Cutting Green Tape initiative, which aims to make it easier to get permits and funding for ecological restoration and stewardship projects. The initiative meshes with the crux of the Science Board’s paper through its emphasis on swift adaptation to changing conditions.

Whether the Delta Independent Science Board’s paper leads to further discussion or action remains to be seen. Its premise, however, seems to resonate.

Whether the Delta Independent Science Board’s paper leads to further discussion or action remains to be seen. Its premise, however, seems to resonate.

“Forward-looking science is vital to this more nimble, flexible, dynamic and adaptive approach for managing ecosystems and water,” said Tatayon with the Delta Stewardship Council. “We must find ways to more reliably fund and support science that goes beyond status-and-trends monitoring or science needed to show compliance with regulations.”

DWR’s Hartman said there is a positive end to the many resources dedicated to understanding the Delta.

“We are doing a lot of really great science as we adapt to the changing conditions,” she said, “and while it’s hard to keep up, we are moving faster every day.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Key Findings: Preparing for a Fast-forward Future in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

The Delta Independent Science Board’s article, Preparing for a Fast-forward Future in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, was derived from several public discussions by current and former members of the science board. The 27-page article suggests that the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta ecosystem is changing rapidly, extreme events are becoming more frequent and thresholds are likely to be crossed more often, creating greater uncertainty about future conditions. It has been submitted for publication to the journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science.

The Delta Independent Science Board’s article, Preparing for a Fast-forward Future in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, was derived from several public discussions by current and former members of the science board. The 27-page article suggests that the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta ecosystem is changing rapidly, extreme events are becoming more frequent and thresholds are likely to be crossed more often, creating greater uncertainty about future conditions. It has been submitted for publication to the journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science.

Its key findings:

- As the effects of climate change gain force, the environment is changing more rapidly. Extreme events — droughts, heat waves, forest fires and floods — are becoming more frequent and more extreme.

- Snowpack from the Sierra Nevada, which accounts for most of the water entering the Delta, has been becoming more variable with greater extremes.

- The pelagic organism decline of 2002 (including Delta smelt) was a rapid change between a prior and subsequent regime – a tipping point. Delta scientists were caught by surprise and were not in a position to inform a management response before a threshold was crossed.

- The 2012 to 2016 drought had profound effects on water flows and salinity levels in the Delta, affecting not only water management but native fish populations and the abundance and distribution of invasive aquatic plants.

- For half a century, it has been known that solutions require multidisciplinary efforts and stakeholder cooperation. Too often, however, the cultures, methods, languages, and infrastructure of different disciplines, agencies, and stakeholder groups create barriers that impede cooperation.