Invasive Species

Invasive species, also known as

exotics, are plants, animals, insects and aquatic species

introduced into non-native habitats.

Invasive species, also known as

exotics, are plants, animals, insects and aquatic species

introduced into non-native habitats.

Often, invasive species travel to non-native areas by ship, either in ballast water released into harbors or attached to the sides of boats. From there, introduced species can then spread and significantly alter ecosystems and the natural food chain as they go. Another example of non-native species introduction is the dumping of aquarium fish into waterways.

Without natural predators or threats, these introduced species then multiply.

Invasive species also put water conveyance systems at risk. Water pumps and other infrastructure can potentially shut down if large numbers of invasive species clog pipelines and equipment.

California

Since the arrival of Western settlers, California has been troubled by invasive species. In one prominent example, eucalyptus trees from Australia have thrived across the state.

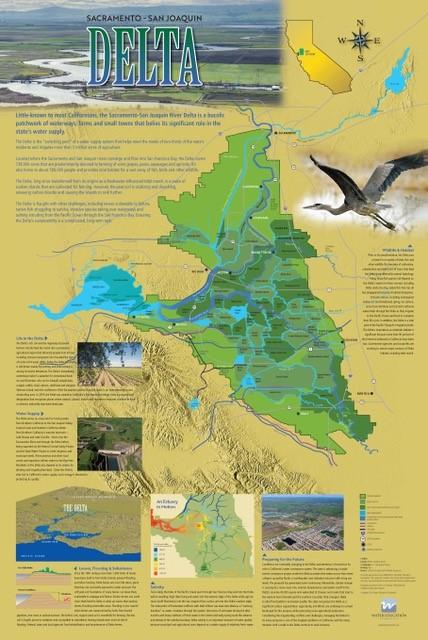

The state’s waterways are also home to some of the densest concentrations of invasive species in the world. This is the case in San Francisco Bay, with its busy ship traffic from around the globe, and the adjoining Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

Invasive species threats have included trout and bass in Lake Tahoe, water hyacinth in the Delta, and quagga mussels in reservoirs along the lower Colorado River and in the Colorado River Aqueduct that carries water to Southern California.

Besides water hyacinth, invasive aquatic vegetation in the Delta includes Brazilian waterweed and water primrose. Invasive vegetation has increased exponentially in recent years, clogging about 17,400 acres of waterways across the Delta, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

Delta invasives alter water flows, water temperature and the amount of oxygen and nutrients in the water. They disrupt sediment transport and turbidity — how clear or cloudy the water is — which in turn affects the quality of habitat for fish, such as longfin and Delta smelt. Decreasing turbidity makes young smelt more vulnerable to predators. Sediment transport also is important because its deposition across marsh plains protects against predicted sea level rise.

Total eradication of these invasive plants from Delta waterways is unlikely because they have spread too widely, according to the USGS.

A large rodent native to South

America known as nutria began causing concern after

invading the Delta. Nutria has a propensity to

devour every bit of vegetation in sight and destabilize levees by

burrowing into them. State agencies are focused on

eradicating nutria from the Delta and have removed more than

5,100 of the animals from the wild since 2017. Federal

legislation was signed into law in 2020 to help fund eradication

efforts.

A large rodent native to South

America known as nutria began causing concern after

invading the Delta. Nutria has a propensity to

devour every bit of vegetation in sight and destabilize levees by

burrowing into them. State agencies are focused on

eradicating nutria from the Delta and have removed more than

5,100 of the animals from the wild since 2017. Federal

legislation was signed into law in 2020 to help fund eradication

efforts.

In October 2024, golden mussels were discovered in the Delta near Stockton, the first confirmed detection of this invasive species in North America, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Like the quagga and zebra mussels, golden mussels rapidly reproduce and grow in dense clusters that can clog water supply pipelines, damage boat hulls and harm native species and sport fish.

However, golden mussels pose a greater threat to California than quagga or zebra mussels because they can live and reproduce in waters with lower calcium levels like those throughout the watersheds of the Sierra Nevada and the Sacramento and Trinity rivers.

Colorado River

Along the Colorado River, once thriving cottonwoods have been crowded out by tamarisk, salt cedar and other exotic plants that erode beaches and degrade wildlife habitat.

In response, the Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program was launched in 2005 to balance use of the river with the conservation of native species and their habitat. The MSCP, which works toward the recovery of species listed under the Endangered Species Act, includes actions such as densely planting riparian conservation areas to reduce invasive species competition with native species.

Learn more about the Endangered Species Act in this video.

To guard against invasive species, California requires ballast water management for ships arriving from distant ports. Depending on the location of their last port of call, ships must exchange the water in their ballast tanks either 50 or 200 nautical miles from land. In addition, arriving vessels of a certain tonnage must discharge in port only the minimum amount of ballast water essential for operations and minimize or avoid uptake of ballast water in areas with known infestations of invasive species.

In 2006, the State Lands Commission issued regulations setting ballast discharge standards and deadlines. The standards were to be implemented in 2020 but, due to a lack of available ballast water treatment technologies, implementation of interim and final standards has been delayed to 2030 and 2040, respectively.

Updated January 2025