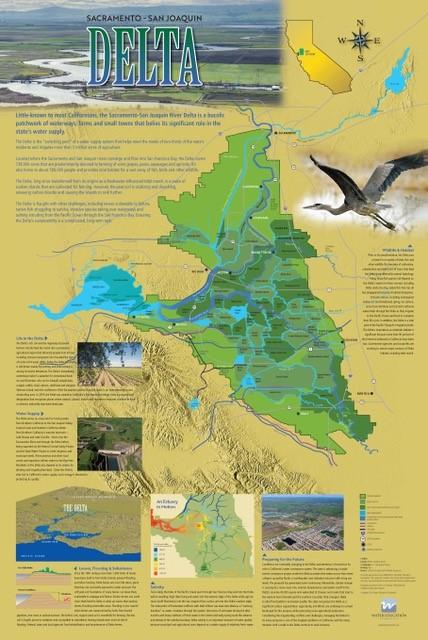

Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta is California’s most crucial water and ecological resource. It is the largest freshwater tidal estuary of its kind on the west coast of the Americas, providing important habitat for birds on the Pacific Flyway and for fish that live in or pass through the Delta. It also the hub of California’s two largest surface water delivery projects, the State Water Project and the federal Central Valley Project. The Delta provides a portion of the drinking water for 27 million Californians and irrigation water for large portions of the state’s $50 billion agricultural industry.

The Delta is formed by the Sacramento River flowing south to meet the north-flowing San Joaquin River just south of Sacramento, where the rivers mingle with smaller tributaries and tidal flows. The rivers’ combined freshwater flows through the Carquinez Strait, a narrow break in the Coast Range, and into San Francisco Bay’s northern arm, forming the Bay Delta. Suisun Marsh and adjoining bays are the brackish transition between fresh and salt water. But the location of that transition is not fixed.

Fed by runoff from the northern Sierra Nevada and southern Cascades mountain ranges, the Delta is a 700-mile maze of sloughs and waterways surrounding more than 60 leveed tracts and islands.

More than a century ago, farmers began building a network of levees to drain and “reclaim” what was then a marsh. Progressively higher levees were built to keep the surrounding waters out, the lands were pumped dry and the marsh was transformed into productive island farms, mostly below sea level. [See Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Timeline].

Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Challenges

The state of California oversees the Delta through the authority of the Department of Water Resources, State Water Resources Control Board, Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Delta Stewardship Council, along with a variety of other state agencies that have specific responsibilities.

Today, 1,100 miles of Delta levees protect farms, cities, schools and people from flooding and related hazards. But Delta islands are as much as 25 feet below the level of the surrounding water. Many of the levees that protect the islands are fragile, leaving them vulnerable to earthquakes and other seismic activities as well as flooding.

More than half-a-million people call the Delta home, living in 14 cities and towns in six counties. It is home to the community of Locke, the only town in the United States built primarily by early Chinese immigrants during the early 20th century. Other legacy communities include Bethel Island, Clarksburg, Courtland, Freeport, Hood, Isleton, Knightsen, Rio Vista, Ryde and Walnut Grove.

Five highways pass through the Delta, as do three railroads, two deep-water shipping channels, hundreds of natural gas lines and five high-voltage transmission lines.

The Delta covers more than 738,000 acres in five counties. It is a prime spot for sportfishing and serves as an important conduit for salmon runs that are crucial to the state’s commercial fishing industry. In addition, at least half of its Pacific Flyway migratory water birds rely on the region’s wetlands.

Controversies

For more than 40 years, the Delta has been embroiled in continuing legal controversy over the struggle to restore the faltering ecosystem while maintaining its role as the hub of the state’s water supply.

Scientists attribute the low numbers of Delta fish species, such as the endangered Delta smelt, to human activities, drought and pumping operations. This issue has been at the center of numerous lawsuits and counter lawsuits from a range of stakeholders such as conservation groups and agricultural interests [see also Delta Litigation].

The many problems affecting the Delta have prompted the question of how it can continue to serve its role as the switching yard for California water while remaining a viable ecosystem, agricultural community and growing residential center.

The export facilities for the federal Central Valley Project (CVP) and State Water Project (SWP) are in the south Delta near Tracy, with pumps powerful enough to reverse the flow of portions of the San Joaquin River. The pumps sometimes have to be ramped down to prevent fish entrainment. Discussions of improving Delta conveyance have occurred for more than 50 years. The State Water Project, begun in the 1960s, had an alternate conveyance system as part of a second phase that was never completed.

In 1982, California voters rejected a statewide ballot proposition that would have authorized construction of a canal and other facilities to divert water around the Delta into the State Water Project.

In 2013, California Gov. Jerry Brown proposed constructing two tunnels to divert Sacramento River water underneath the Delta. As part of an updated Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP), it would have included three intake pipes in Sacramento County near the town of Clarksburg, just south of Sacramento. Modern fish screens would also be in place to better protect fish from being sucked into the pipes. The diverted water would be sent to farmland and communities elsewhere in the state.

The BDCP itself was re-branded under the Brown administration as the $15 billion California Water Fix/EcoRestore when it was determined that the regulatory agencies could not provide the 50-year assurance of protecting the imperiled species sought by the water agencies. EcoRestore seeks to create or restore 30,000 acres of Delta and Suisun Marsh habitat – including aquatic, sub-tidal, tidal, riparian, floodplain and uplands. Most of the work is already required because of existing biological opinions and will be funded by CVP and SWP contractors. The rest, about 25 percent, is covered by bond and other funds through state agencies.

The controversial tunnel proposal, meanwhile, was scaled back in 2019 when Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order that effectively canceled the twin tunnels in favor of a smaller, single tunnel with a carrying capacity of between 3,000 cubic feet per second and 7,500 cubic feet per second. DWR has been drafting a proposal for the “Delta Conveyance” single tunnel, including compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act and ways to reduce permanent and temporary impacts to the Delta.

In its 2019 update of the Delta Plan, the Delta Stewardship Council noted that beyond the debate and controversy, the object of the plan is a Delta landscape that remains essentially itself while adapting gradually and gracefully to a future.

“We want a Delta ecosystem that works markedly better than today’s, reflected partly in a resurgence of native fish,” the Plan said. “And we want an end to the endless wrangling about Delta flows and plumbing – a truce that can only be achieved if the entire California water system undergoes a measure of reform.”