Golden Mussel, California’s Newest Delta Invader, Is Likely Here To Stay – And Spread

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: Aquatic hitchhiker adds to burden of invasive mussels challenging water agencies across the West

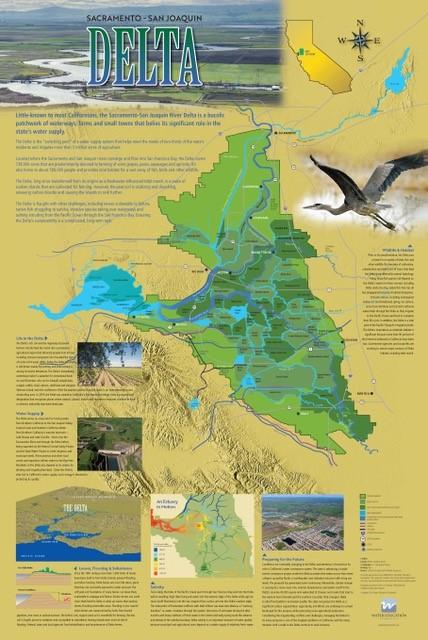

A new aquatic invader, the golden mussel, has penetrated California’s ecologically fragile Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the West Coast’s largest tidal estuary and the hub of the state’s vast water export system. While state officials say they’re working to keep this latest invasive species in check, they concede it may be a nearly impossible task: The golden mussel is in the Golden State to stay – and it is likely to spread.

A new aquatic invader, the golden mussel, has penetrated California’s ecologically fragile Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the West Coast’s largest tidal estuary and the hub of the state’s vast water export system. While state officials say they’re working to keep this latest invasive species in check, they concede it may be a nearly impossible task: The golden mussel is in the Golden State to stay – and it is likely to spread.

The fingertip-size mussel is believed to have hitchhiked into the Delta in the ballast water of a freighter from Asia that docked at the Port of Stockton. The mussel was first detected there in October 2024, and its discovery set off alarm bells among water managers and environmental scientists. The reason: Unlike their cousins the quagga mussels, which have infested major Colorado River facilities in Southern California, golden mussels can tolerate a wider range of aquatic environments and may have more opportunities to do so.

The golden mussel is just the newest invasive headache for water agencies across the West. Quagga mussels turned up in the lower Colorado River in 2007, and agencies in California, Arizona and Nevada that draw water from the river have had to intensify monitoring and costly maintenance to try to limit their impact. Another cousin, the zebra mussel, was discovered last summer in the upper Colorado River in Colorado. The zebra mussel also has turned up in a small reservoir in San Benito County south of San Francisco that, as a result, has been closed to the public since 2008.

In Northern California, federal, state and local water managers are already trying to limit the golden mussels’ spread. They’re inspecting boats entering and leaving many lakes and reservoirs or have even shut down boat ramps entirely until more is known about the threat. And operators of state and Northern California water agencies have stepped up monitoring, inspections and cleaning of equipment where they’ve found mussels.

State officials believe the golden mussels may have arrived a couple of years ago given their size and spread. The mussels have been found as larvae and adults in about 30 areas around the central and southern Delta. More concerning because it suggests a wider infestation, golden mussels have been detected in O’Neill Forebay at the foot of San Luis Reservoir in Merced County. The reservoir impounds water exported from the Delta by both the State Water Project and the federal Central Valley Project, two of California’s largest water projects. From O’Neill, golden mussels could potentially spread deep into the San Joaquin Valley via the Central Valley Project, and all the way to San Diego through the State Water Project.

Andrew Cohen, director of the Center for Research on Aquatic Bioinvasions based in Richmond, believes that their presence in O’Neill Forebay is just an indicator of things to come.

Given how far they’ve spread from the Delta and how interconnected the state and federal water projects are, Cohen said, “there’s no precedent for thinking we’re going to be able to eradicate them.”

A different kind of mussel

Golden mussels are native to the rivers and creeks of Southeast Asia and can be distinguished by the yellow-brown hue of their shell. While they were known to have spread to South America, they had not been detected in North America until their discovery in the Delta last fall.

They are prolific reproducers and prodigious filter feeders that can alter the food web, rob native species of food sources and, by clarifying source water, contribute to algal blooms. Golden mussels are an added burden in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, which already must contend with more than 185 other non-native plants, fish and animals.

They are prolific reproducers and prodigious filter feeders that can alter the food web, rob native species of food sources and, by clarifying source water, contribute to algal blooms. Golden mussels are an added burden in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, which already must contend with more than 185 other non-native plants, fish and animals.

Golden mussels are similar in size and shape to quagga and zebra mussels, which have invaded other waters of the state but not the heart of the Delta.

Like their more established cousins, golden mussels are known to attach in clusters to hard surfaces like pipelines and other water system infrastructure, clogging pipes and screens. Clearing them from water facilities could add millions to maintenance costs.

An important factor that differentiates golden mussels is biology. They are able to complete their lifecycle in water bodies with lower calcium levels than what is needed to sustain shell growth for quagga or zebra mussels. That means more areas of the California watershed are vulnerable to infestation.

“We have to up the ante now (on resources) because more water bodies are open to an infestation by invasive mussels and all the consequences that brings.”

~Thomas Jabusch, senior environmental scientist with California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife

Eradicating mussels from larger bodies of water is nearly impossible, experts say. Nascent efforts in South America employ genetic splicing to produce sterile golden mussels in the hopes that in the wild they will neutralize proliferation. Whether it will work remains to be seen.

Quagga and zebra mussels have been eradicated only from closed systems where water has been drawn down to expose the mussels to air or by flooding the water body with a chemical biocide. Neither of those methods is possible in the Delta. Chemical treatment could affect a host of other life forms.

“We can’t draw the Delta down. We can’t flood it with any kind of biocide,” said Cohen, with the Center for Research on Aquatic Bioinvasions. “It’s just not possible to do those things, aside from the fact that the environmental impacts will be such that we would never do them.”

With eradication unlikely, Thomas Jabusch, a senior environmental scientist with California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife, said more resources are going to be needed to contain golden mussels and limit their spread. “We have to up the ante now,” he said, “because more water bodies are open to an infestation by invasive mussels and all the consequences that brings.”

Slowing the inevitable

If golden mussels do spread throughout California, experience with mussel infestations elsewhere suggest it may take years or decades to occur. Cohen noted that in the East, zebra and quagga mussels have spread slowly, riding the flow of water or hitchhiking on boats.

Their impact on the Great Lakes, however, has been costly. A 2021 report titled Economics of Invasive Species estimated that zebra mussels cause $300 million to $500 million annually in damages to power plants, water systems and industrial water intakes in the Great Lakes.

Their impact in California, so far, has been more limited. The state Department of Water Resources spends around $3.3 million annually on early mussel detection and prevention at its various State Water Project facilities.

Additional prevention costs are shouldered by California State Parks and Los Angeles County. The focus right now is on preventing golden mussels from proliferating.

Tanya Veldhuizen, Special Projects Section Manager for DWR’s Environmental Assessment Branch, said that efforts are being made to increase the cleaning of infrastructure, application of anti-fouling coatings, and manual cleaning and flushing of small diameter piping. Boats are required to pass inspection before entering a State Water Project reservoir. If they fail inspection, boats must dry out for seven days.

All watercraft leaving State Water Project reservoirs with established golden or quagga mussel populations are required to undergo an exit inspection in which boat drain plugs are pulled so that all residual water in bilges, livewells and ballasts drains out.

All watercraft leaving State Water Project reservoirs with established golden or quagga mussel populations are required to undergo an exit inspection in which boat drain plugs are pulled so that all residual water in bilges, livewells and ballasts drains out.

Some facilities – like the East Bay Municipal Utility District’s Pardee and Camanche reservoirs and the Bureau of Reclamation’s New Melones Lake, all in the Sierra foothills – have elected to suspend boat launches until the threat from golden mussels can be better evaluated.

California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife uses three methods to search for mussels. They check their infrastructure by looking and feeling for mussels. They also place sediment samplers in strategic locations to see if mussels are growing on them. Finally, they filter plankton out of the water and then look at those samples under microscopes.

“Once mussels are in a water body, it’s more about control and containment than specifically about eradication,” Jabusch said. “The main focus should really be on prevention; containment in the places where they currently are and preventing water bodies that don’t have mussels from getting mussels.”

Containing the Spread of Mussels

Metropolitan Water District, which serves 19 million Southern Californians as the largest supplier of treated water in the United States, has been on the front lines of the battle against quagga mussels and expects a lengthy fight to keep its infrastructure clear of golden mussels. Although a costly nuisance, the mussels don’t directly affect the quality of treated drinking water, Metropolitan says.

Paul Rochelle, Metropolitan’s water quality manager, said that chemical controls have played a large role in controlling the spread of quagga mussels.

Metropolitan Water District continually injects a low dose of chlorine into three locations of the Colorado River Aqueduct to target quagga mussel larvae and keep them from settling and becoming adults. The annual cost just for chlorine is between $3 million and $5 million, Rochelle said.

“The challenge with chlorinating large volumes of water or large distances of water is that chlorine eventually either dissipates or it gets bound up by organic material in the water,” Rochelle said. “So we apply chlorine at the start of the Colorado River Aqueduct. And by 12 to 15 or so miles in, much of the chlorine has dissipated.”

“If you can prevent the infestation, job done. It’s a lot harder to eradicate them once they’re established.”

~Paul Rochelle, water quality manager for Metropolitan Water District of Southern California

Metropolitan crews also put muscle into mussel control. Every year, the entire aqueduct is shut down for three weeks for routine maintenance, allowing it to dry out and for mussels to be scraped off the concrete and equipment. Those costs for quagga control are part of the agency’s larger operation and maintenance budget, he said, and aren’t broken out.

Rochelle said it would be harder to chlorinate State Water Project pipelines because the water has different characteristics than Colorado River water. Chlorine could react with organic matter in the State Water Project and produce potentially harmful disinfection byproducts. Still, he said, water agencies are evaluating the feasibility of chemical controls due to the lingering presence of quagga mussels in Pyramid and Castaic lakes in Northern Los Angeles County, which receive State Water Project water.

Quagga mussels were first found in both Pyramid and Castaic lakes in 2016. Years later, the frequency of the mussels significantly increased. Metropolitan believes the calcium concentration in Lake Castaic increased enough so that quagga mussels could thrive. What accounts for the rise in calcium is hard to pin down, but Rochelle said wildfires may release calcium in the soil and rain may wash that into the water.

Two of Metropolitan’s reservoirs in Riverside County, which receive Colorado River water, have also been infested with quagga mussels. But a third reservoir, the massive Diamond Valley Lake, Southern California’s largest at 810,000 acre-feet, quit receiving Colorado River water about a year before quaggas were discovered. The lake now receives only State Water Project water and has been protected from quagga infestation by rigorous boat inspections.

Two of Metropolitan’s reservoirs in Riverside County, which receive Colorado River water, have also been infested with quagga mussels. But a third reservoir, the massive Diamond Valley Lake, Southern California’s largest at 810,000 acre-feet, quit receiving Colorado River water about a year before quaggas were discovered. The lake now receives only State Water Project water and has been protected from quagga infestation by rigorous boat inspections.

“If boat inspections hadn’t been effective, then it’s possible Diamond Valley Lake would’ve been infested by now,” Rochelle said.

For now, Rochelle believes the best prevention against the spread of golden mussels lies in monitoring. Metropolitan conducts eDNA testing on plankton samples that can identify golden and quagga genetic material. It is consulting with other agencies on the best way to protect bodies of water connected to the State Water Project.

“Because if you can prevent the infestation, job done,” Rochelle said. “It’s a lot harder to eradicate them once they’re established.”

Reach Editor Douglas E. Beeman at dbeeman@watereducation.org

Know someone who wants to stay connected to water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water and follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram.