Imported Water Built Southern California; Now Santa Monica Aims To Wean Itself Off That Supply

WESTERN WATER SPOTLIGHT: Santa Monica is tapping groundwater, rainwater and tighter consumption rules to bring local supply and demand into balance

Imported water from the Sierra

Nevada and the Colorado River built Southern California. Yet as

drought, climate change and environmental concerns render those

supplies increasingly at risk, the Southland’s cities have ramped

up their efforts to rely more on local sources and less on

imported water.

Imported water from the Sierra

Nevada and the Colorado River built Southern California. Yet as

drought, climate change and environmental concerns render those

supplies increasingly at risk, the Southland’s cities have ramped

up their efforts to rely more on local sources and less on

imported water.

Far and away the most ambitious goal has been set by the city of Santa Monica, which in 2014 embarked on a course to be virtually water independent through local sources by 2023. In the 1990s, Santa Monica was completely dependent on imported water. Now, it derives more than 70 percent of its water locally.

The switch has been accomplished through an extensive plan that encompasses small measures like toilet replacements, household rain harvest barrels and aggressive conservation to large measures like cleaning up contaminated groundwater, capturing street runoff and recycling water.

Dean Kubani, assistant public works director for the city of 93,000 residents hemmed in along the Southern California coast, said the effort is driven by the recognition that its imported supplies from the State Water Project and the Colorado River through Metropolitan Water District of Southern California are vulnerable.

“We are getting ahead of the game and

setting ourselves up for having a very stable water supply that

is diversified and going to be able to meet the needs of our

community for the future,” he said.

“We are getting ahead of the game and

setting ourselves up for having a very stable water supply that

is diversified and going to be able to meet the needs of our

community for the future,” he said.

For several years, Santa Monica has been evaluating its water demand and ways to increase the local supply while accelerating existing water-saving programs such as retrofits, rebates for water conservation improvements and landscape conversion that reduce use. Reaching that 100 percent target will be achieved through boosting local supplies while further cutting demand, Kubani said.

What Cost for Water Independence?

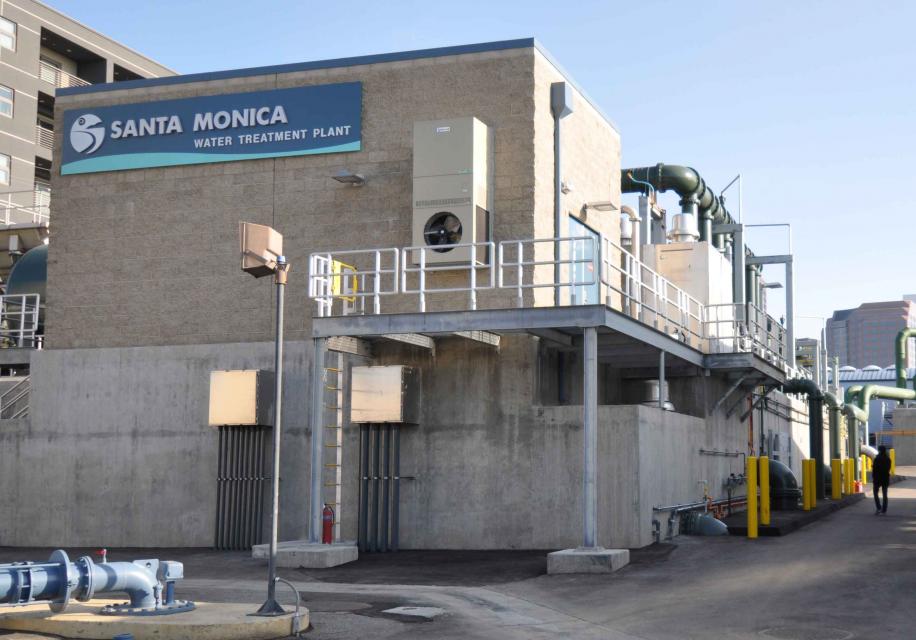

The city is diversifying its water supply portfolio through initiatives that it says will help offset imported water purchases from Metropolitan – upgrading its facility to capture and recycle urban runoff for landscape irrigation (freeing up potable water for domestic use), constructing an advanced purification facility to recharge aquifers and upgrading the city’s water treatment plant with new technology to increase overall production.

To help finance improvements, the city in 2015 approved a series of annual water rate increases of as much as 9 percent a year through the end of 2019.

Despite the rate increases, city staff say Santa Monica’s water rates continue to be “significantly lower” than nearby Los Angeles, Beverly Hills and Culver City. Moreover, Kubani said, in about 20 years the city’s water costs will be less by using more local supplies than if it had continued using imported water.

A significant boost in local

supplies came when Santa Monica reclaimed groundwater

contaminated with gasoline additives MTBE and TBA. New treatment

facilities allowed five key wells to come back online in

2011.

A significant boost in local

supplies came when Santa Monica reclaimed groundwater

contaminated with gasoline additives MTBE and TBA. New treatment

facilities allowed five key wells to come back online in

2011.

On average, Santa Monica now gets 30 percent of its water supply, 4,100 acre-feet annually, from Metropolitan (a rainy start to the 2019 water year has reduced that figure to between 8 and 12 percent, according to Miranda Iglesias, a city spokeswoman). Local groundwater is a key component of the water supply outlook going forward, providing a buffer against drought.

“Our contingency plan is to build additional wells in the coastal subbasin where the city has identified additional water sources but is currently studying the water quality and determining feasibility,” Iglesias said.

Managing the Aquifer

The groundwater basin beneath Santa Monica is designated a medium-priority basin under California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, so a groundwater sustainability plan isn’t due to the state until January 2022. Still, the city recognizes that its plan to tap groundwater further depends on managing it properly.

“You obviously can’t endlessly pump as much as you want out of our groundwater reservoirs,” Kubani said. “We came up with a very conservative figure of how much we could reliably pump yearly without drawing down the aquifers.”

The remaining gap in supplies will be

met through a municipal rainwater capture system with a capacity

of 6 million gallons expected to be operational in 2020. A

subsurface treatment plant capable of treating as much 1 million

gallons daily will take stormwater and sewage flows, treat them

to an advanced level and inject the water into the aquifer so it

can be pumped up later when needed.

The remaining gap in supplies will be

met through a municipal rainwater capture system with a capacity

of 6 million gallons expected to be operational in 2020. A

subsurface treatment plant capable of treating as much 1 million

gallons daily will take stormwater and sewage flows, treat them

to an advanced level and inject the water into the aquifer so it

can be pumped up later when needed.

“Those three things combined – the conservation, the local groundwater and alternative supplies — are going to help us meet our demand so that we won’t have to buy [imported] water,” Kubani said.

Mark Gold, associate vice chancellor of environment and sustainability at the University of California, Los Angeles, has worked with Santa Monica as an adviser and chairs the city’s task force on the environment. He said the city is on track to meet its 2023 target because of its water neutrality ordinance — which seeks to cap water use for new developments to an average of the past five-year historical use for that individual parcel — and its capital improvement plan.

“It is a comprehensive plan with about a $120 million price tag,” he said. “Some of it, like a large stormwater capture cistern, has already been built.”

Growing local water supplies

Metropolitan is supportive of efforts to expand local water supplies even if Santa Monica will be paying less money to the Southern California water wholesaler. As part of its long-range planning, Metropolitan has pursued a strategy of water supply diversification that includes investing in recycled water, pursuing water conservation and offering its member agencies incentives to invest in alternative supplies. The agency projects another 3.5 million people in the region by 2040.

“In order to accommodate that growth, you are going to need to see continued management of per capita demand … and we are going to have to grow the amount of local supplies,” Deven Upadhyay, Metropolitan’s assistant general manager said. “If you don’t do those things, what’s going to happen? All of those 3.5 million people who are coming in and all of that demand for water is going to fall on the imported system and that’s not sustainable.”

While imported water will remain one of the pillars of Southern California’s water supply, it’s clear that water managers are striving to ensure a reliable future. By 2023, Santa Monica expects to purchase only about 1 percent of its water supply from Metropolitan— primarily to maintain the service line in case of emergencies.

“Based on what we know now with climate change, it really doesn’t make sense to continue importing water from the Colorado River and from Northern California,” Kubani said. “That’s going to be much more expensive and it’s not a sustainable supply of water.”

Further Reading

- Western Water: In Water-Stressed California and the Southwest, An Acre-Foot of Water Goes a Lot Further Than It Used To, Oct. 5, 2018

- Western Water: As Colorado River Stakeholders Draft a Drought Plan, the Margin for Error in Managing Water Supplies Narrows, Dec. 20, 2018

- Water Academy: Groundwater

- Aquapedia: Urban Conservation

- Aquapedia: Overdraft

- Aquapedia: Colorado River Aqueduct

- Aquapedia: California Aqueduct

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.