Aquifers

Aquifers are an unseen but critical resource in California’s water supply system.

These natural basins that sit below the surface are found underneath 40 percent of California’s land area.

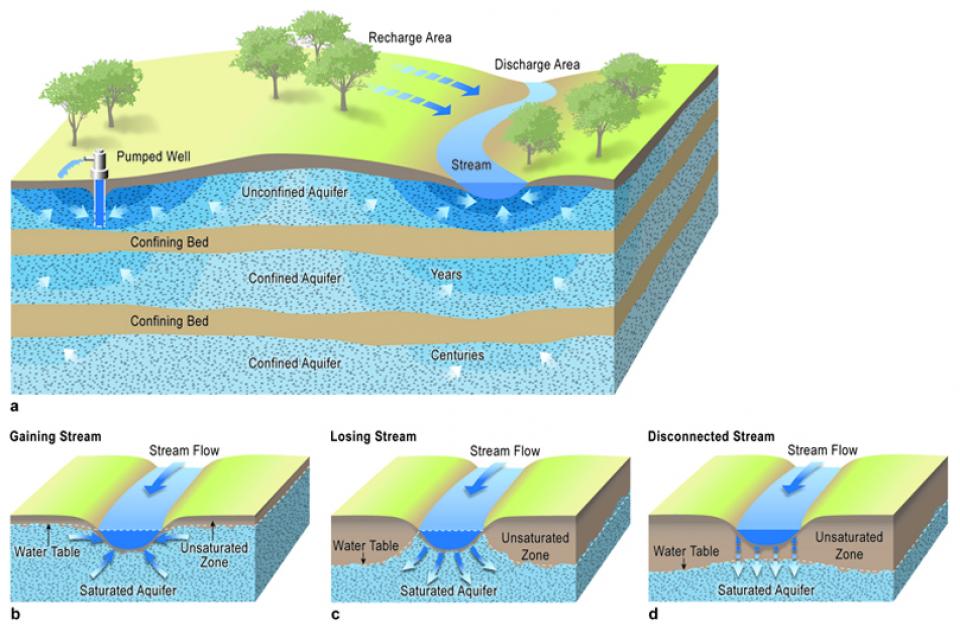

Aquifers come in two types. Some are formed in the space between porous materials such as sand, gravel, silt or clay and are known as alluvial aquifers (sediments deposited by flowing water) or unconfined aquifers. However, in many places across California, there are aquifers beneath a rock layer that does not allow water to permeate in measurable amounts. These are known as confined aquifers.

Confined aquifers that are under pressure are known as artesian aquifers. This pressure can push water to the surface, which when drilled are called artesian wells. Aquifers can also be several feet deep or several thousand feet deep and can be found across California, from the brackish coast to the Central Valley to the desert interior.

This diverse geography brings with it a range of challenges. Adding to those challenges, California uses more groundwater — the main water source for aquifers — than can be replaced naturally or artificially.

Aquifers Overview

Aquifers play an important role as a source of freshwater for urban areas and agricultural irrigation. Unlike surface water, which is mostly found in the northern and eastern parts of the state, aquifers are widely distributed throughout California. Additionally, they are also often found in places where freshwater is most needed, for instance, in the Central Valley and Los Angeles.

Similar to a below-ground sponge, aquifers are the natural accumulation of runoff and precipitation. Below the surface, this runoff then percolates into crevices between rocks, silt and other material.

Generally, water purveyors prefer to tap aquifers closest to the surface because it is more practical and cheaper to pump. Alluvial aquifers, confined by looser material, are also favorable sources of groundwater rather than the tougher confined aquifers. However, some confined aquifers, if drilled, can contain enough pressure to drive water to the surface without a pump.

Overall, aquifers — as a subsurface natural reservoir — also help meet California’s increasing demand for groundwater. About 40 percent of the state’s water needs are met by groundwater in normal years and as much as 60 percent during a drought. Groundwater dependence varies, from as little as 5 percent in the San Francisco Bay Area to 83 percent in the Central Coast region. Water officials also view depleted aquifers as good places to store water for use in the future, a process known as groundwater banking.

As California’s population continues to grow, new challenges confront aquifer use as the state tries to balance groundwater sustainability with demand for water.

Aquifer Challenges

Surging demand for water, and such related practices as overdrafting, have burdened aquifers and connected ecosystems in recent decades. In 2014, California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act was enacted, requiring governments and water agencies to halt overdraft and bring the most affected groundwater basins into balanced levels of pumping and recharge.

In consequence, depleted aquifers are vulnerable to both natural and man-made contamination.

With nature, elements such as radon and arsenic can leach into aquifers that have been drawn down. Meanwhile, lowered levels of freshwater in the top layers of aquifers can also expose heavier salt water sitting at the bottom, degrading water quality. At the same time, along the coast, particularly in the highly agricultural Pajaro and Salinas valleys of Central California, seawater can also intrude into depleted aquifers.

Similarly, in some cases, salty groundwater can come from ancient seawater that was isolated in the subsurface sediments until pumping began. The northern San Joaquin Valley near Stockton has problems with pockets of seawater that are drawn via pumps into the freshwater aquifers. In the northern Sacramento Valley, some pumpers are at risk of tapping into ancient deposits of sea water, which can degrade the quality of the groundwater.

Man-made pollutants, once thought to be filtered out by the soil, are now known to harm water quality as well. These contaminants include industrial solvents and pesticides.

In some cases, the challenges to aquifer sustainability are being addressed by recharging aquifers with surface water (rather than waiting for them to refill naturally) through a process called conjunctive use.

In other situations, proper management of aquifers is still in development, particularly as courts have established that groundwater may be pumped and used on land far from the original source.