Drought

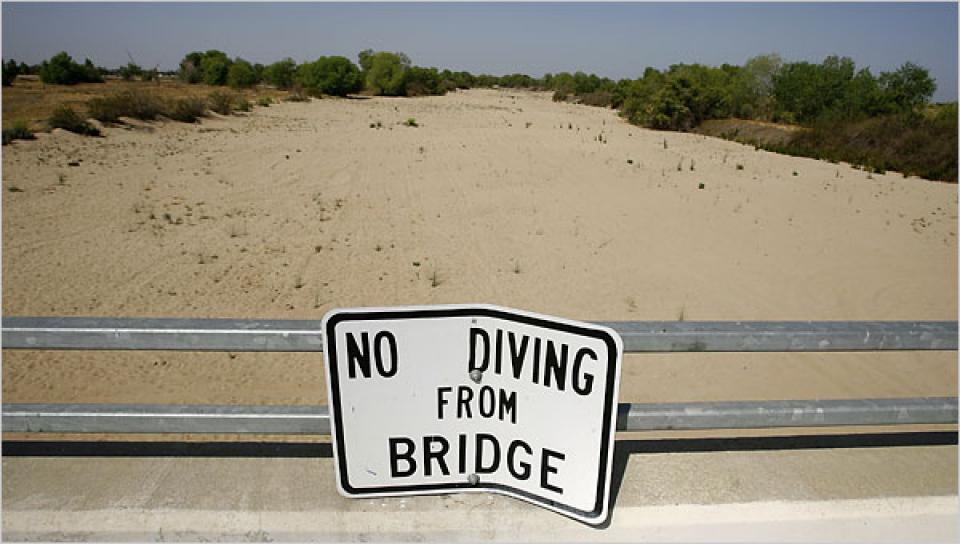

Drought—an extended period of limited or no precipitation—is a fact of life in California and the West, with water resources following boom-and-bust patterns. During California’s 2012–2016 drought, much of the state experienced severe drought conditions: significantly less precipitation and snowpack, reduced streamflow and higher temperatures. Those same conditions reappeared early in 2021 prompting Gov. Gavin Newsom in May to declare drought emergencies in watersheds across 41 counties in California.

No portion of the West has been immune to drought during the last century and drought occurs with much greater frequency in the West than in any other region of the country. Between 2000 and 2020, the Colorado River Basin experienced the driest 21-year period in the 115-year historical record. Only five years of above-average inflow occurred during that time.

Most of the West experiences what is classified as severe to extreme drought more than 10 percent of the time, and a significant portion of the region experiences severe to extreme drought more than 15 percent of the time, according to the National Drought Mitigation Center.

Click here to get the latest developments on drought in California and across the West in our Aquafornia news.

Droughts generally happen gradually. Water stored in reservoirs and groundwater blunt the effects of drought and influence when the state is deemed to be in drought, according to the California Department of Water Resources (DWR). A single dry year does not lead to drought in California because of the state’s extensive water infrastructure, including major reservoirs and groundwater resources.

There is no universal definition of when a drought begins or ends, nor is there a state statutory process for defining or declaring drought, according to DWR. Furthermore, it is important to distinguish between drought conditions and a state of emergency. The former is a condition of prolonged dryness that causes impacts; the latter is a statutory finding that enables specified actions.

Experts say a drought occurs about once every 10 years somewhere in the United States. Water shortages to forests, aquatic ecosystems, hydroelectric power plants, rural drinking water supplies, agriculture and cities can cause billions of dollars in economic losses.

Because droughts cannot be prevented, experts are looking for better ways to forecast them and new approaches to managing droughts when they occur.

Responding to Droughts

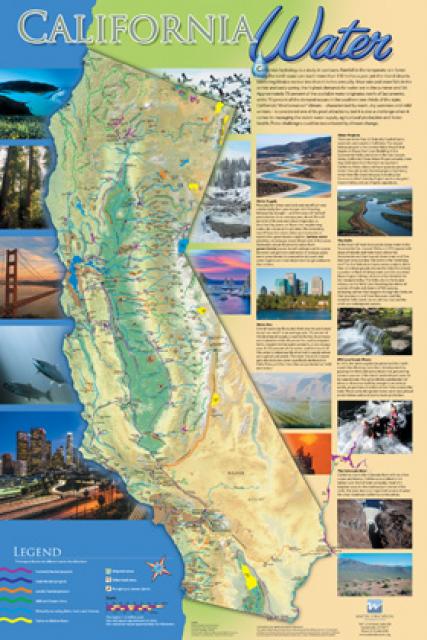

Throughout the West, states have responded to the typical pattern of flooding and drought by building a plumbing network of dams, reservoirs and canals that capture rainfall and snowmelt runoff.

The systems are designed to collect surface runoff during winter months, when precipitation generally is plentiful, and store it for use during summer months, when rainfall is virtually nonexistent.

As long as precipitation occurs in normal amounts, these systems work quite well, but they become stressed if precipitation levels fall below normal for even a couple of years. The problem lies in the fact that much of the West is an arid desert that water has transformed into farms, homes and businesses.

Such transformation created an agricultural empire in California’s Sacramento, San Joaquin and Imperial valleys while facilitating the developments of vast amounts of land for housing. In consequence, demands for water by people, farms and the environment have generated controversy and conflict because, even in years with abundant precipitation, the supply of water is not always able to match the need. In dry years, there is simply not enough water to go around.

The frequency and severity of droughts have also prompted new thinking about long-term planning for future droughts and the effects that possible permanent climate changes could have on water supplies. Although few scientists dispute the trend of drier and warmer conditions, others warn that the 2.7-degree anticipated increase in California temperatures could have disastrous consequences for water supplies in the future.

Droughts traditionally have been managed as crises, using short-term, ad hoc water management measures that often disappear once precipitation returns to normal levels.

Major Droughts

A severe California drought in 1976

and 1977 served as a wake-up call for the state, helped spark the

water conservation

movement, and spurred the creation of the Water Education Foundation to educate the

public and lawmakers on California’s critical water issues.

A severe California drought in 1976

and 1977 served as a wake-up call for the state, helped spark the

water conservation

movement, and spurred the creation of the Water Education Foundation to educate the

public and lawmakers on California’s critical water issues.

More long-term plans for mitigating the effects of droughts should be made before water shortages occur, crisis management experts say, and should include water resources monitoring, graduated water conservation measures and public education.

The 2012-2016 drought – one of the deepest, longest and warmest of California’s historical droughts – tested the state’s drought preparedness. In January 2014, then-California Gov. Jerry Brown proclaimed a state of emergency and directed state officials to take all necessary actions to prepare for drought conditions.

In 2015, the state set a new low when the April snowpack was recorded at 5 percent of the April 1st average, making the 2015 water year the driest winter in the state’s recorded history. (The water year runs from October 1 to September 30.) Californians responded to the state’s pleas to conserve water. During June, July and August 2015, water agencies met or exceeded Gov. Brown’s call for a 25 percent reduction in water use.

An extremely wet winter in 2016-2017 left the Sierra snowpack at 164 percent of normal by April 2017, leading Gov. Brown to declare an end to the drought emergency. But the lessons learned remained. In 2018, new laws created a long-term water conservation framework for California based on wise water use, eliminating water waste, and improved agricultural water use efficiency.

Shortly after taking office in 2019, Gov. Newsom called on state agencies to deliver a Water Resilience Portfolio to meet California’s urgent challenges, including drought risks.

Below average precipitation returned in 2019 and 2020. Conditions were exceptionally bad in 2021 as the Sierra snowpack dwindled to virtually nothing. Newsom in April declared a state of emergency for drought in Sonoma and Mendocino counties as local reservoir levels receded. That was followed in May by an expanded declaration to include 39 more counties covering the watersheds of the Klamath River, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Tulare Lake.

In 2023, California saw a return to flood conditions and an epic snowpack. Water year 2024 saw average statewide precipitation, resulting in a snowpack at 110% of average at the end of the season, according to the California Department of Water Resources.

The 2025 water year in California has been characterized as a “winter of extremes,” experiencing a mix of both heavy rainfall and dry weather. California’s snowpack in the Sierra Nevada measured 96% of average on April 1, the third straight year of near-average or above-average amounts of snow.

Updated in June 2025