Dams

Dams have allowed Californians and others across the West to harness and control water dating back to pre-European settlement days.

Today, California and neighboring states are home to a vast integrated system of federal, state and locally owned dams that help with flood management, water storage and water transport. Flood management projects, for example, have prevented billions of dollars’ worth of damage and countless lives from being lost. Hydropower from dams also provides a relatively pollution-free source of electricity, and has helped lessen dependence on oil, gas and coal. Hydropower typically generates about 15 percent of the annual electricity in California, according to the California Energy Commission.

There are 1,472 federal dams and state-regulated dams in California, with an unknown number of smaller, private dams that do not fall under the state’s jurisdiction.

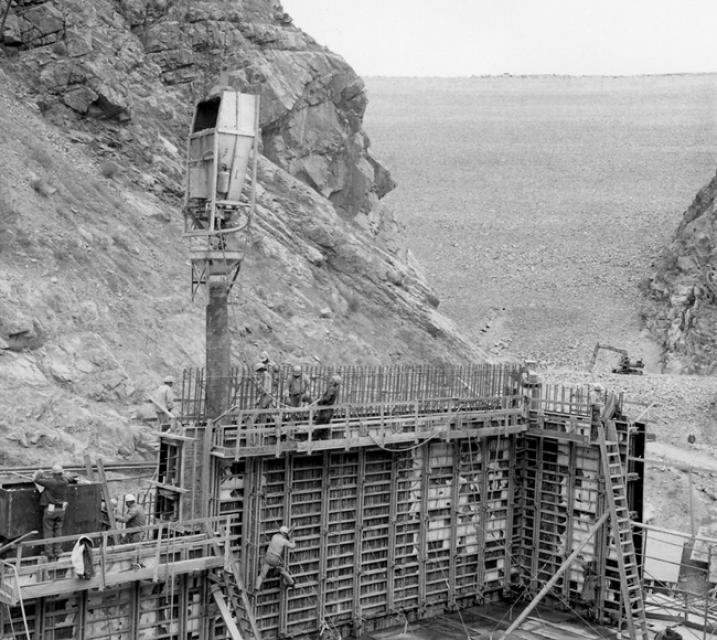

There are many types of dams (concrete, timber, masonry and earthen) for a variety of purposes (flood control, water supply, mining tailings impoundment, debris and diversion). Major water supply and flood control dams such as Shasta, Oroville and Folsom are concrete or embankment dams, which describes the type of materials used to build the dams. Primary types of concrete dams are gravity, arch and roller-compacted concrete. Embankment dams like Oroville are very common and can be comprised of soil, rock or a blending of the two.

Dams focus primarily on storing water and then getting the water to the right place at the right time. In California, this system has helped spark important economic activity in arid or semi-arid areas of the state, including the agricultural Central Valley and Southern California.

As part of this, nearly 75 percent of

the available water originates in the northern third of the state

(north of Sacramento), while 80 percent of the demand occurs in

the southern two-thirds of the state. The demand for water is

highest during the dry summer months when there is little natural

precipitation or snowmelt. California’s capricious climate also leads to extended

periods of drought and major

floods.

As part of this, nearly 75 percent of

the available water originates in the northern third of the state

(north of Sacramento), while 80 percent of the demand occurs in

the southern two-thirds of the state. The demand for water is

highest during the dry summer months when there is little natural

precipitation or snowmelt. California’s capricious climate also leads to extended

periods of drought and major

floods.

To help meet this demand, a series of dams were built on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada for both flood control and water supply. These include Oroville Dam on the Feather River, Folsom Dam on the American River and Friant Dam on the San Joaquin River.

Dams and the Future

Changing public values and a greater awareness about ecosystems and the importance of keeping them healthy have generated governmental and private efforts to lessen some of the impacts caused by damming rivers. Water officials say achieving a careful balance among agricultural, urban, and environmental interests is considered key.

In 1972, for instance, the state Legislature moved to preserve the North Coast’s free-flowing rivers from development by passing the California Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, preserving about a quarter of the state’s undeveloped water in its natural state. The act prohibits construction of dams or diversion facilities, except to serve local needs, on portions or entire rivers around the state.

More recently, there has been a growing trend of storing water underground and interest in off-stream dams. Sub-surface storage in aquifers has several advantages over surface water storage. Sub-surface storage is far less damaging to the environment than the construction of reservoirs and dams, and usually does not require an extensive distribution system. Water banked underground also has a much lower evaporation rate than surface reservoirs. One drawback, however, is sometimes litigious water rights issues.

In November 2014 voters passed Proposition 1, the Water Quality, Supply and Infrastructure Improvement Act, which included $2.7 billion for the public benefit aspect of surface water reservoirs and groundwater storage. In 2018, the California Water Commission conditionally awarded $816 million in Prop. 1 money to build Sites Reservoir, an off-stream reservoir an hour northwest of Sacramento, and $459 million to expand Los Vaqueros Reservoir, an off-stream reservoir in eastern Contra Costa County. Construction of both projects is tentatively scheduled for completion in 2029.

There are some dams in the state being eyed for removal because they are obsolete – choked by accumulated sediment, seismically vulnerable or out of compliance with federal regulations that require environmental balance. Dam removal is expensive, usually exceeding $100 million, not including the cost of initial studies. But for some dam owners the cost of removal is less expensive than effecting the necessary modifications such as fish ladders or seismic safety retrofits.

In the Klamath River Basin there is an effort to restore the river by removing four hydroelectric dams — the largest such project in U.S. history. The aim is to improve water quality, revive fisheries and boost tourism. A 2020 agreement by California, Oregon, the Yurok Tribe, the Karuk Tribe, PacifiCorp and the Klamath River Renewal Corporation describes how the parties will implement the 2016 Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement and sets the terms for the removal of the four dams. Removal of the first dam began in 2023 and all four dams were taken out by the end of 2024.

In California, the average age of the 1,246 dams that fall under the jurisdiction of the Department of Water Resources’ Division of Safety of Dams (DSOD) is 70 years. Following the 2017 Oroville spillways incident, then-Gov. Jerry Brown directed DSOD to conduct more detailed evaluations of dam appurtenance structures, such as spillways, to include geologic assessment and hydrological modeling. Brown ordered the new review to be expedited for dams that have spillways and structures similar to Oroville Dam before the next flood season. In 2020, a team of experts, including an independent review board, determined that the Oroville Dam complex is safe to operate and no urgent repairs are needed.

DSOD’s dam condition assessments were largely based on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ National Inventory of Dams’ five condition-rating definitions: satisfactory, fair, poor, unsatisfactory and not rated. Dams rated as satisfactory have no identified dam safety deficiencies. Dams rated as fair, poor or unsatisfactory have at least one identified dam safety deficiency.

According to DSOD, 1,145 dams within its jurisdiction are rated satisfactory, with no identified deficiencies. There are 101 dams with identified dam safety deficiencies that are rated as fair, poor, or unsatisfactory. DSOD may require a restriction of the reservoir storage to a specific level if unsafe conditions exist or require the dam owner to implement other risk reduction measures until remedial actions can be implemented.