Shasta Dam

Shasta Dam forms California’s

largest storage reservoir, Shasta Lake, which can hold about 4.5

million acre-feet.

Shasta Dam forms California’s

largest storage reservoir, Shasta Lake, which can hold about 4.5

million acre-feet.

As the keystone of the federal Central Valley Project, Shasta stands among the world’s largest dams. Construction on the dam began in 1938 and was completed in 1945, with flood control as the highest priority.

Located 12 miles north of Redding, Shasta traps the cold waters of the Pit and McCloud rivers and the headwaters of the Sacramento River behind its 602-foot curved, concrete face. Roughly 90 percent of the water stored in Shasta Lake comes from rainfall. The reservoir accounts for about 41 percent of the stored water in the Central Valley Project.

In years of normal precipitation, the Central Valley Project stores and distributes about 20 percent of the state’s developed water — about 7 million acre-feet —through its massive system of reservoirs and canals. Water is transported 450 miles from Lake Shasta in Northern California to Bakersfield in the southern San Joaquin Valley. Along the way, the Central Valley Project has long-term agreements with more than 250 contractors in 29 of California’s 58 counties.

Shasta Dam and Operations

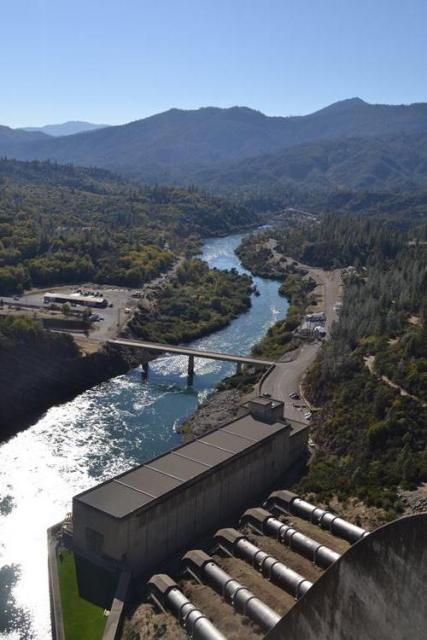

Associated facilities include Shasta Powerplant, located just below the dam, with a generating capacity of 710,000 kilowatts, or enough power to meet the needs of between 355,000 and 710,000 homes.

Ten miles downstream is Keswick Dam, reservoir and power plant. Keswick Dam creates an afterbay for Shasta Dam and the Trinity River diversion facilities, stabilizing uneven water releases from the power plants.

As with most multipurpose projects, the CVP’s operational priorities change with the seasons. From November to April, flood control is the top priority and reservoirs are filled to store winter runoff. From May to October, releases are timed to satisfy a variety of water-supply needs and create room for flood flows. At Shasta, the reservoir typically is drawn down to a flood reservation volume by early December, and maximum storage is normally reached in late May or June.

Similar to the Oroville Dam, construction of Shasta Dam blocked access to 187 miles of cold water streams, about half the available spawning and rearing habitat in the upper Sacramento River system.

Watch a video about the history of Shasta Dam and the Central Valley Project.

During Shasta’s construction, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service worked with the Bureau of Reclamation to mitigate this habitat loss. Coleman National Fish Hatchery, located near the mouth of Battle Creek where it joins the Sacramento River, was built in 1943 to offset the loss of anadromous fish that could no longer reach their spawning grounds upstream of Shasta.

Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery at the base of Shasta Dam was established in 1997. It is the only hatchery in the world that raises winter-run chinook salmon and is one of two captive brood stock programs for Delta smelt in California.

Today, there are three types of migratory barriers to anadromous fish within Battle Creek: natural waterfalls, hydroelectric diversion dams, and the Coleman Hatchery weir.

There are efforts underway to restore and enhance the endangered winter-run chinook salmon.

Reclamation made numerous operational changes. A temperature control device on the upstream face of Shasta Dam releases varying amounts of water from three depths (to a maximum depth of 350 feet) to maintain favorable downstream temperatures for spawning fish. Other actions include closing the Delta Cross Channel gates for several months to keep migrating salmon in the river channel.

Shasta Dam and the Future

According to Reclamation, enlarging

the reservoir would improve water supply

reliability, reduce flood damages and improve water

temperatures in the Sacramento River below the dam for anadromous

fish survival.

According to Reclamation, enlarging

the reservoir would improve water supply

reliability, reduce flood damages and improve water

temperatures in the Sacramento River below the dam for anadromous

fish survival.

Raising the dam 18.5 feet, for example, would mean an additional 636,000 acre-feet a year, enough water to sustain 2 million people a year. Opponents say the amount of water made available by raising the dam is not worth the ecosystem costs —flooding of canyons and endangering wildlife and habitat —and further loss of sacred tribal ground (an issue unresolved from the original construction).

Congress in 2018 set aside $20 million for design and preconstruction work on the project. The state of California went to court in 2019 to block CVP contractor Westlands Water District from assisting in the planning and construction of a dam raise. A subsequent ruling granted a preliminary injunction halting Westlands’ participation in the project. California opposes the project because it would inundate a reach of the McCloud River, which is designated as a California wild and scenic river.

Meanwhile, the Bureau of Reclamation is conducting the Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation to evaluate enlarging Shasta Dam and Reservoir. As the investigation progresses, Reclamation plans to continue related work on environment, water rights and Native American and cultural resources.