Allowing Water Systems to Crash is Not an Option

Western Water Expert Pat Mulroy Urges Peace in California Water Disputes

“Gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.” Geologist and Explorer John Wesley Powell at an irrigator convention in 1883.

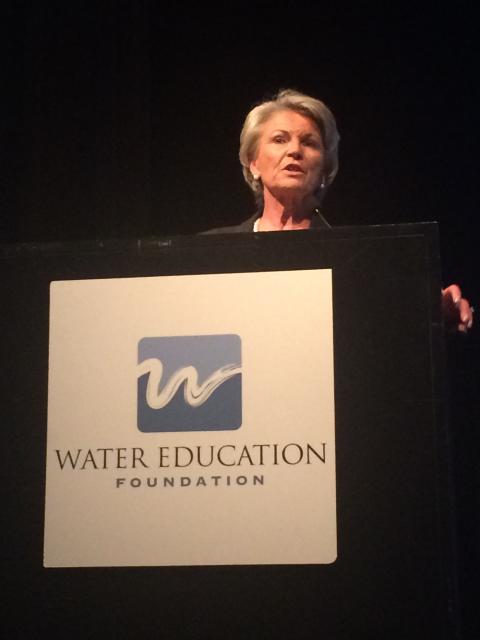

“In 1883 we had very little understanding of what the flows of the Colorado River were, we had less understanding of the incredible changes in the climate that would be happening over the course of the next 100 years, which we finally came to realize as we entered this century,” said Pat Mulroy, who served as general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority from 1989 to 2014.

Mulroy called Powell’s words “prophetic” as she opened the Anne J. Schneider Fund lecture series last Thursday at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento.

During her tenure at the water authority, Mulroy proved to be a force to be reckoned with as she helped propel the seven Colorado River Basin states to change their mindset about how to manage water in the system and begin to address major challenges – drought, over-allocation and climate change.

“Sitting here in Sacramento it’s probably very difficult to imagine that you are inextricably linked to the Colorado River system,” Mulroy told the audience of about 140 people. “The [Sacramento-San Joaquin] Delta system and the Colorado River system have been wed together and they will not be separated.”

For instance, extreme drought conditions in 2014 meant cutbacks in State Water Project deliveries. The country’s largest supplier of treated water, Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, a State Water Project contractor, had to then draw upon water it was storing in Lake Mead to augment its annual allocation.

“The Colorado River system had to bear an additional burden because Metropolitan had to pull out virtually everything it had stored in Lake Mead, driving that lake down further,” she said.

Mulroy said managing water as we have done in the past is no longer acceptable. “The standard way of reacting to drought has been we use our water in good years, and when we go into drought, we go into draconian drought planning; we take draconian measures, and we weather through those years. Then we heave a big sigh of relief when it snows or rains, and we go right back to what we were doing before.”

“That will not work going into the future,” she emphasized. “Allowing the system to crash is not a viable option.”

Fortunately, during the past couple of years of drought, players in the Colorado River system are coming to a new understanding and stepping up to take a collective responsibility.

For example, during 2015 a pilot project among three water districts – Central Arizona Project, Metropolitan and SNWA – and the federal government, “put taxpayer and ratepayer money on the table to lease water for one year from willing farmers, leave that water in Lake Mead with no one’s name on it. No one ever gets to take that water for their own use,” Mulroy said. “Every one of us has an obligation to preserve the system. We are all equally dependent on it. Our communities cannot survive without it.”

However, California still has much work to do. If water managers don’t reach agreements, she warned, the courts will impose their will. “There’s nothing more important to us in the Colorado River basin than for there to be peace in California — there’s nothing more important for the sake of any number of national parks, tribes, city dwellers and farmers up and down the basin than for California to find a logical, rationale, methodological way to work with one another,” she said.

“We are all in awe of California – the things you accomplish, the economy you enjoy, the vastness of the agricultural produce that you have, the leadership you have in so many places around the state. Finding common ground should be more natural here than it is anywhere else.”