California Weighs Changes for New Water Rights Permits in Response to a Warmer and Drier Climate

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: State Water Board report recommends aligning new water rights to an upended hydrology

As California’s seasons become

warmer and drier, state officials are pondering whether the water

rights permitting system needs revising to better reflect the

reality of climate change’s effect on the timing and volume of

the state’s water supply.

As California’s seasons become

warmer and drier, state officials are pondering whether the water

rights permitting system needs revising to better reflect the

reality of climate change’s effect on the timing and volume of

the state’s water supply.

A report by the State Water Resources Control Board recommends that new water rights permits be tailored to California’s increasingly volatile hydrology and be adaptable enough to ensure water exists to meet an applicant’s demand. And it warns that the increasingly whiplash nature of California’s changing climate could require existing rights holders to curtail diversions more often and in more watersheds — or open opportunities to grab more water in climate-induced floods.

“California’s climate is changing rapidly, and historic data are no longer a reliable guide to future conditions,” according to the report, Recommendations for an Effective Water Rights Response to Climate Change. “The uncertainty lies only in the magnitude of warming, but not in whether warming will occur.”

The report says climate change will bring increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, such as atmospheric rivers and drought, prolonged fire seasons with larger fires, heat waves, floods, rising sea level and storm surges. Already, the state is experiencing a second consecutive dry year, prompting worries about drought. “The wet season will bring wetter conditions during a shorter period, whereas the dry season will become longer and drier,” the report said.

The State Water Board report catalogues 12 recommendations — inserting climate-change data into new permits, expanding the stream-gauge network to improve data and refining the means to manage existing water rights to ensure sufficient water is available to meet existing demands. At the same time, the report says, the State Water Board should build on its existing efforts to allow diverters to capture climate-driven flood flows for underground storage.

Because floods and the magnitude of the peak flows are expected to increase under many climate change projections, “there may be greater opportunity to divert flood and high flows during the winter to underground storage,” the report said. The State Water Board could build on the flood planning data used by the Department of Water Resources to help inform water availability analyses and to spell out conditions for the resulting water right permits for floodwater capture.

“Water rights can either be something that helps us adapt and create resiliency … or it can really hinder us.”

~Joaquin Esquivel, State Water Resources Control Board Chair

“The recommendations are a menu of options,” said Jelena Hartman, senior environmental scientist with the State Water Board and chief author of the report. The goal, she said, was to “clearly communicate what the water rights issues are and what we can do.”

The result of a 2017 State Water Board resolution detailing its comprehensive response to climate change, the report could be the first step toward a retooled permitting system for new water rights applications. (The Board has averaged about a dozen newly issued permits per year, mostly for small diverters, since 2010.) The State Water Board is seeking public comments on the report through March 31.

And while the report does not call for reopening existing permits, it does sound a warning for those permit holders: With droughts projected to become longer and more severe, the State Water Board may need to curtail water diversions more often and in more watersheds.

Time to ‘Reset Expectations’?

During a March 18 webinar on the report, Erik Ekdahl, the State Water Board’s deputy director for the Division of Water Rights, said it may be time to “reset expectations” regarding curtailments for water use permits, given that curtailments have only been implemented by the state in 1976-1977 and 2014-2015.

“That’s not an overuse of curtailments,” he said. “If anything, it’s an underuse. We may need to look at curtailment more frequently.”

Some water users fear the report

could be the beginning of a move to restrict their access.

Some water users fear the report

could be the beginning of a move to restrict their access.

“To the extent climate change is incorporated into water rights administration, it should be to respond to a changing hydrology in a manner that is protective of existing users … and not to turn back the clock on water rights or to service new ambitions for instream flows that aren’t in the law,” said Chris Scheuring, senior counsel with the California Farm Bureau Federation.

The report notes that many of California’s existing water rights are based on stream gauge data drawn during a relatively wet period (since about 1955). Although California has had some of its most severe droughts on record since the 1970s, annual flow on many streams is highly variable due to California’s Mediterranean climate. Fluctuations in year-to-year precipitation are greater than any state in the nation, ranging from as little as 50 percent to more than 200 percent of long-term averages.

If climate conditions swing drier

overall, the report says, it will be difficult for those existing

water right holders to divert their permitted volume. Expanding

the network of stream and precipitation gauges will be critical,

the report says, to improving the accuracy of water availability

analyses.

If climate conditions swing drier

overall, the report says, it will be difficult for those existing

water right holders to divert their permitted volume. Expanding

the network of stream and precipitation gauges will be critical,

the report says, to improving the accuracy of water availability

analyses.

But the report’s focus is on new water rights applicants and the need to weave climate change data into their permits to provide a clear description of projected water availability. “We take the long view in asking if there is sufficient water available for a new appropriation,” Hartman said.

State Water Board leaders said the water rights response is part of the umbrella of actions needed to confront climate change.

“Water rights can either be something that helps us adapt and create resiliency … or it can really hinder us,” Chair Joaquin Esquivel said at the Board’s Feb. 16 meeting where the report was presented.

Writing Climate Change into New Permits

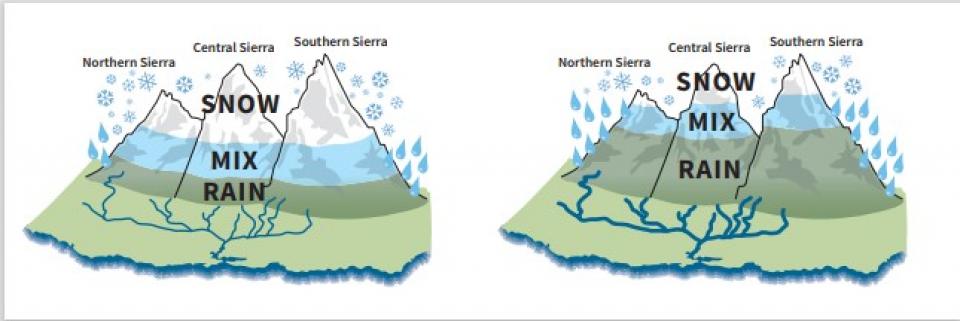

The fingerprints of climate change are increasingly evident in California’s seasonal weather. Extreme conditions are on the upswing. Peak runoff, which fuels the state’s water supply, has shifted a month earlier during the 20th century. The four years between 2014 and 2017 were especially warm, with 2014 the warmest on record. Annual average temperatures in California are projected to rise significantly by the end of the century.

“We are already experiencing the impacts of climate change,” said Amanda Montgomery, environmental program manager with the State Water Board. The continuous warming creates an “unambiguous trend” toward less snow, she said, and shifts in snowpack and runoff are relevant for water management and water rights.

Jennifer Harder, a water rights

expert who teaches at the University of Pacific’s McGeorge School

of Law in Sacramento, said integrating climate change

considerations into water rights permits is good policy that

aligns with the State Water Board’s mission of ensuring the

highest and most beneficial use of water.

Jennifer Harder, a water rights

expert who teaches at the University of Pacific’s McGeorge School

of Law in Sacramento, said integrating climate change

considerations into water rights permits is good policy that

aligns with the State Water Board’s mission of ensuring the

highest and most beneficial use of water.

“It’s beyond dispute that the changes in precipitation and temperature patterns resulting from climate change will affect water availability,” she said.

Kimberly Burr, a Sonoma County environmental attorney and member of the North Coast Stream Flow Coalition, told the State Water Board at the Feb. 16 meeting that knowledge about the effects of climate change on water is sufficient enough to be incorporated into new water rights permits. It’s an important issue, she said, because the state must ensure adequate flows exist to protect endangered species, vulnerable communities and public needs under the public trust doctrine.

“There is a finite amount of water and we have to prepare for the worst and move forward with great caution,” she said.

A Challenging Water Rights System

Water rights in California are based on a permitting system that includes several specifics, such as season and point of diversion and who can continue taking water when there is not enough to supply all needs. Getting a water right permit can take from several months for a temporary permit to several years for a permanent right.

In deciding whether to issue permits, the State Water Board considers the features and needs of the proposed project, all existing and pending rights, and the necessary instream flows to meet water quality standards and protect fish and wildlife.

The priority of a water right is particularly important during a drought, when some water right holders may be required to stop diverting water according to the priority of their water right. Suspension of right is done through curtailments of the user’s ability to divert water.

If the State Water Board implemented

the recommendations in the water rights and climate change

report, critics say, it would add another component in a system

that aims to meet the demand for additional water. Already, local

groundwater agencies are lining up to get access to available

water sources for aquifer recharge and groundwater banking so

they can comply with the state’s Sustainable Groundwater

Management Act.

If the State Water Board implemented

the recommendations in the water rights and climate change

report, critics say, it would add another component in a system

that aims to meet the demand for additional water. Already, local

groundwater agencies are lining up to get access to available

water sources for aquifer recharge and groundwater banking so

they can comply with the state’s Sustainable Groundwater

Management Act.

Some question whether putting the report’s recommendations into action would possibly hinder the permitting process.

“The concern I have is we have quite a big backlog already and it’s already challenging to get through the system,” said State Water Board Vice Chair Dorene D’Adamo, who serves as its agriculture member. “How do we incorporate all of this and still be nimble and move with deliberate speed?”

Incorporating a climate change response into new water rights permits would be complicated, but necessary, State Water Board member Tam Doduc said.

Striving For Complete Data

Adding climate change data to water rights permits applications is problematic because of questions about the precision of existing data and the degree to which it can be localized.

“Current climate change models have

disparate findings, and many are calibrated for a global scale

but not regional areas,” Lauren Bernadett, regulatory advocate

with the Association of California Water Agencies, told the

Board. “The recommendations insert significant uncertainty for

any person or agency applying for a permit.”

“Current climate change models have

disparate findings, and many are calibrated for a global scale

but not regional areas,” Lauren Bernadett, regulatory advocate

with the Association of California Water Agencies, told the

Board. “The recommendations insert significant uncertainty for

any person or agency applying for a permit.”

Harder, the law professor, said good data is critical for determining water availability, but perfect data to achieve absolute certainty is unattainable. “There are many different facets of water management and it requires us to give careful thought into how we make decisions in the face of the data we have, knowing it will never be perfect and always be changing” she said.

Better streamflow data is crucial to knowing whether the water exists to support new permits. The report notes that the low number of gauges, particularly on the smaller stream systems in California, means there is often not enough information to accurately characterize hydrologic variability over years or decades. That significantly limits the ability to reliably estimate water availability.

The report says the state may need to rethink how it estimates water availability. It added that one way to improve accuracy may be temporary installation of portable stream gauges at requested diversion points.

Moving From Theoretical To Practical

Addressing how to respond to climate change in water rights permitting would be a substantial undertaking, particularly given the existing array of complex and controversial matters on the State Water Board’s agenda.

“We don’t have all the details yet and this won’t be an easy task. Too often we focus on our water quality activities because water rights are too difficult.”

~Tam Doduc, State Water Board member

“We don’t have all the details yet and this won’t be an easy task,” Doduc said. “Too often we focus on our water quality activities because water rights are too difficult.”

Said Esquivel: “There is a lot of work to be done and it can seem overwhelming. But there is a lot of great groundwork and a commitment to making sure the water rights system is going to adapt and be here for us when we need it most.”

The State Water Board already has broad authority under existing law to take on climate change in water rights permits should it decide to do so, said Harder, with McGeorge Law School.

“What the board is trying to do,” she said, “is snap those tools together in a new way and polish up the edges.”

However the issue proceeds, Harder said, the state should recognize that water resources are best understood by the local agencies that have the most pertinent information about them.

“We need to approach this as a partnership as opposed to looking at it through the lens of … state power vs. local power,” she said. “There is an important role for both here.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.