As Climate Change Erodes Western Snowpacks, One Watershed Tries A ‘Supershed Approach’ To Shield Its Water Supply

WESTERN WATER SPOTLIGHT: Groundwater banks, a high-elevation reservoir and improved weather forecasting are how American River water managers hope to replace the disappearing Sierra Nevada snowpack

The foundation of California’s water

supply and the catalyst for the state’s 20th century

population and economic growth is cracking. More exactly, it’s

disappearing.

The foundation of California’s water

supply and the catalyst for the state’s 20th century

population and economic growth is cracking. More exactly, it’s

disappearing.

Climate change is eroding the mountain snowpack that has traditionally melted in the spring and summer to fill rivers and reservoirs across the West. Now, less precipitation is falling as snow in parts of major mountain ranges like California’s Sierra Nevada and the Rockies in the West, and the snow that does land is melting faster and earlier due to warming temperatures.

Scientists warn the shift to more rain and less snow will become more pronounced due to climate change, presenting a particular challenge to California, which gets approximately a third of its water used by humans from Sierra Nevada snowmelt. The problem is so severe California officials expect the state could lose 10 percent of its water supply by 2040, largely due to reduced mountain snowpacks.

Hoping to get ahead of that dismal forecast, managers of a major Sierra Nevada watershed east of Sacramento are replumbing their water systems to better handle bursts of rain instead of trickling snowmelt. Their “Supershed Approach” to replace the loss of the once-reliable snowmelt calls for climate adaptation projects that stretch from the headwaters of the American River west of Lake Tahoe, to the foothills and down to the valley floor in Sacramento.

“We can’t think like we used to, the [watershed] systems are no longer the same.”

~Rosemary Carroll, research professor of hydrology, Desert Research Institute

Prescribed burns, high-elevation reservoirs, updated reservoir-operation strategies and enhanced aquifer recharge are key pieces of the fledgling portfolio that state officials and water experts cast as a holistic approach to planning for climate change. The top-to-bottom management strategy could stand up as a model for other watersheds that are expected to experience stronger, more frequent snow droughts.

“We can’t think like we used to, the systems are no longer the same,” said Rosemary Carroll, research professor of hydrology at the Desert Research Institute who studies snow-fed watersheds in both the Sierra Nevada and Colorado River Basin. “Using old tools is no longer a viable option both environmentally and economically. We’ve got to think a little bit outside the box.”

Snowmelt Is Key

The Sierra Nevada, Spanish for “snowy mountain range”, naturally functions as California’s largest reservoir, storing snow that ideally melts slowly over the spring and summer months and is captured by approximately 200 downstream reservoirs. The amount of snow that falls in the mountains and lasts through the late winter and into early spring is a determining factor in how much surface water will be allocated to California’s cities and businesses — including its $51 billion agricultural industry — and whether restrictions are imposed on water users.

But in recent decades, the snowpack that recharges critical reservoirs like Lake Oroville, New Melones Lake and Folsom Lake, has become less reliable. The key factors affecting the size of snowpack — temperature and precipitation – have been trending in the wrong direction across the West. In the American River Basin alone, air temperatures are projected to increase steadily and cause earlier peak runoff periods.

California saw a glimpse of what a

snowless future looks like in 2015 when the Sierra Nevada

snowpack was measured at just 5 percent of its historical

average. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the dearth of

snow led to a reservoir replenishment rate that was only

about 9 percent of normal and resulted in statewide urban water

use restrictions.

California saw a glimpse of what a

snowless future looks like in 2015 when the Sierra Nevada

snowpack was measured at just 5 percent of its historical

average. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the dearth of

snow led to a reservoir replenishment rate that was only

about 9 percent of normal and resulted in statewide urban water

use restrictions.

Relying on healthy spring blankets of snow draped across the Sierra Nevada’s granite peaks will become an ancient luxury for water managers: By the late 2040s, researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory predict the mountain range could experience multi-year snow droughts. A warmer climate also will lead to a higher percentage of mountain runoff being absorbed by dry soils and thirsty plants or lost through evaporation.

“The whole system is just releasing less water,” said Carroll, the hydrologist at the Reno-based Desert Research Institute. “More snow is going directly back into the atmosphere; it’s not going back into the rivers.”

Not only are snowless winters predicted for the Sierra Nevada, the mountains that sustain the Colorado River Basin are also looking at a barren future. Scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research warn that in some parts of the Rocky Mountains, the amount of water contained in the snowpack at the end of an average winter could shrink by nearly 80 percent toward the end of the 21st century.

Supershed Approach

Water managers have experience dealing with California’s notoriously variable weather but mitigating the major loss of snowpack is forcing them to consider ways to augment infrastructure that was designed for a different climate.

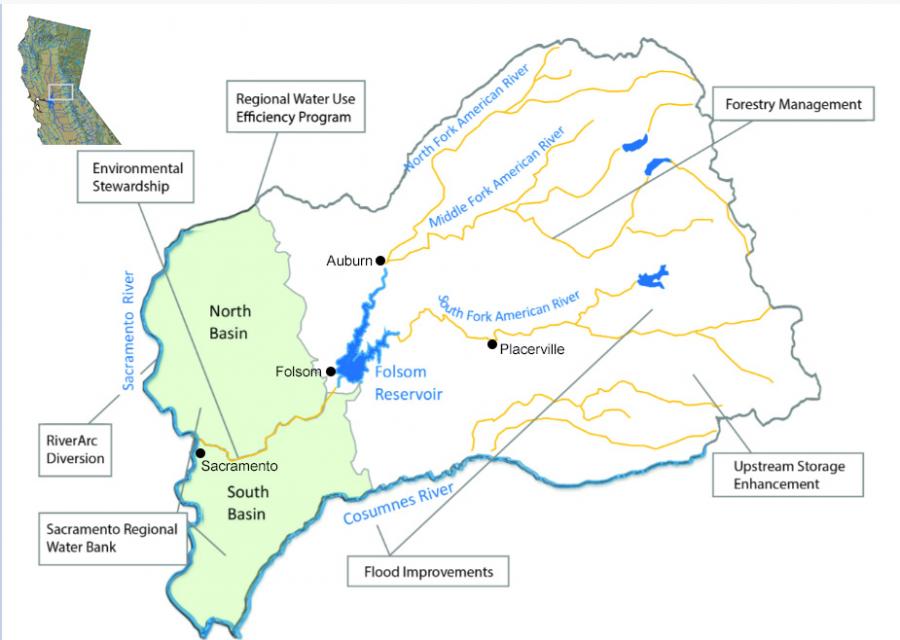

In the sprawling 2,140 square-mile American River watershed, a group of agencies is planning climate adaptation projects to protect the drinking water supplies of more than 2 million people in the Sacramento region.

“If all of our precipitation is going to come as rain instead of snow, it means that we have to find new ways to store water that will sustain our region through the summer and into the dry fall,” said Andy Fecko, general manager of the Placer County Water Agency, which operates 170 miles of canals within the watershed and supplies treated water to Auburn and Roseville in the Sacramento metropolitan area.

Fecko’s agency and an assortment of others that rely on the American River have developed a “Supershed Approach” to buffering the loss of snowmelt. The portfolio outlines forest management projects near the river’s headwaters, a high-elevation reservoir to better capture rain, flood control enhancements and a regional groundwater bank located at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers that’s designed to store up to 90,000 acre-feet of water during a wet year.

The consortium of Sacramento-area water agencies, known as the Regional Water Authority, argue the projects are even more imperative in light of a recent study by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation that found winter temperatures in the American River watershed could spike nearly 5 degrees by the end of the century. The study also estimated that the region will have to increase groundwater pumping by up to 155,000 acre-feet a year to account for the loss of snowmelt and runoff.

“Water management in the basin is expected to be more challenging in the future due to climate pressures that include warming temperatures, shrinking snowpack, shorter and more intense wet seasons and rising sea levels,” Reclamation’s Ernest Conant, director of the agency’s California-Great Basin Region, said in a news release about the study. The federal agency operates Folsom Dam along the river as part of the Central Valley Project.

Coupled with more above- and

below-ground water storage to capture rain, the portfolio aims to

also improve flood control by funneling water during major storms

to farmland and other high-capacity groundwater recharge areas.

Fecko said there’s enough space basin-wide to bank an additional

1.5 million acre-feet, or 50 percent more than the current

storage capacity of Folsom Lake,

the Sacramento region’s largest reservoir.

Coupled with more above- and

below-ground water storage to capture rain, the portfolio aims to

also improve flood control by funneling water during major storms

to farmland and other high-capacity groundwater recharge areas.

Fecko said there’s enough space basin-wide to bank an additional

1.5 million acre-feet, or 50 percent more than the current

storage capacity of Folsom Lake,

the Sacramento region’s largest reservoir.

Meanwhile on the federal side, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is raising Folsom Dam by 3.5 feet to increase the amount of water that can be stored during extreme weather events. The project is slated for completion in 2025 and will create an extra 42,000 acre-feet of reservoir storage.

In addition, Reclamation is expanding forecast-informed reservoir operations at the reservoir. Known as FIRO, it incorporates recent improvements in weather forecasting technology and is intended to give reservoir operators the ability to deviate from strict flood management guidelines when preparing for atmospheric river events. FIRO is being tested at several other California watersheds such as the Russian, Feather and Santa Ana river basins.

California’s 10% Plan

Amid the driest three-year stretch in history, California Gov. Gavin Newsom in August issued a startling announcement: the state was bracing for a potential 10 percent loss of its water supply over the next 20 years. To counteract the climate change-induced deficit, Newsom said, the state was setting a goal of creating up to 4 million acre-feet of new water storage and increasing its wastewater recycling capabilities, among a variety of other projects.

Jeanine Jones, interstate resources

manager at the California Department of Water Resources, said the

state’s major water infrastructure, primarily dams, are due for

an update as most haven’t been invested in since they were built

decades ago.

Jeanine Jones, interstate resources

manager at the California Department of Water Resources, said the

state’s major water infrastructure, primarily dams, are due for

an update as most haven’t been invested in since they were built

decades ago.

“As we look at a warming climate, not only do individual communities need to do things such as water recycling, conservation or desalination … we have to think about adapting some of our backbone infrastructure so we can take these high flows when they become available on a very intermittent basis in big storms and make better use of them,” said Jones during a recent news conference.

Newsom’s blueprint also calls for 430 new stream gauges to be deployed across the state as well as improved snowmelt forecasting to aid local water managers and reservoir operators.

“To account for climate change, we must simulate the physics of interactions among the atmosphere, water as rain or snow, and the land surface – and we need to do this for individual watersheds,” the document states.

A Holistic Blueprint

Western snowpacks, which for decades have functioned as slow-melting water savings accounts, are nearing default. American River water agencies are attempting to make up for the snow loss by renovating existing infrastructure and opening new underground storage accounts to bank future floodwater.

The top-to-bottom approach to managing the American River watershed is intended to protect the rapidly growing Sacramento region’s water supply, but the Regional Water Authority’s projects will have benefits throughout California. As the second largest tributary to the Sacramento River, most of the American River’s flows end up in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta system that provides drinking water to 27 million Californians and irrigates millions of acres of farmland.

“If all of our precipitation is going to come as rain instead of snow, it means that we have to find new ways to store water that will sustain our region through the summer and into the dry fall.”

~Andy Fecko, general manager, Placer County Water Agency

Fecko, with the Placer County Water Agency, said Sacramento ratepayers can’t afford to foot the bill for the entire suite of projects, noting the regional groundwater bank alone is expected to cost roughly $300 million.

“We only use 7 percent of the [American River’s] water so it argues for, we think, outside sources of money to help us complete the [climate] adaptations,” said Fecko.

For now, the state, which has designated more than $8 billion over the last three years toward water supply projects across California, is monitoring whether the supershed approach can be adopted in other snow-fed watersheds.

“Focusing on just an individual facility is rather limiting and expanding and working with the coordination and collaboration needed to do a more holistic watershed approach does have a lot of merit,” said Mike Anderson, California State Climatologist.

“The American River is an interesting example of that process,” he continued. “And it will be very interesting to see what comes out of it as I think it could be used then as a blueprint for other watersheds to try.”

Reach Writer Nick Cahill at ncahill@watereducation.org, and Editor Doug Beeman at dbeeman@watereducation.org.

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook , Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.