Key California Ag Region Ponders What’s Next After Voters Spurn Bond to Fix Sinking Friant-Kern Canal

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: Subsidence chokes off up to 60% of canal’s capacity to move water to aid San Joaquin Valley farms and depleted groundwater basins

The whims of political fate decided

in 2018 that state bond money would not be forthcoming to help

repair the subsidence-damaged parts of Friant-Kern Canal, the

152-mile conduit that conveys water from the San Joaquin River to

farms that fuel a multibillion-dollar agricultural economy along

the east side of the fertile San Joaquin Valley.

The whims of political fate decided

in 2018 that state bond money would not be forthcoming to help

repair the subsidence-damaged parts of Friant-Kern Canal, the

152-mile conduit that conveys water from the San Joaquin River to

farms that fuel a multibillion-dollar agricultural economy along

the east side of the fertile San Joaquin Valley.

Yet the need remains to carry water from Friant Dam, northeast of Fresno, south to the 15,000 farms all the way to Bakersfield. But the carrying capacity of the Friant-Kern Canal has been reduced by as much 60 percent in some places because of the long-term overdraft of groundwater aquifers. That’s not only a problem for farmers, who need that water to grow oranges, grapes and nuts, among other valley crops, but also for those seeking to comply with the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

In addition to halting overdraft, the law requires local agencies to demonstrate how they will convey water to recharge depleted groundwater basins.

“From a SGMA perspective, our success in maintaining our sustainability and keeping our permanent plantings alive and our growers growing is 100 percent reliant on a fully functional Friant-Kern Canal,” said Eric Quinley, general manager of the Delano-Earlimart Irrigation District straddling Kern and Tulare counties.

Proposition 3 would have provided $750 million to address the subsidence problems affecting the canal, but it was defeated at the polls in November in a close vote (50.6 percent to 49.3 percent), partly because of criticism by the Sierra Club and others that taxpayer dollars should not be used to deal with the problem.

“Overpumping of aquifers caused the

groundwater subsidence that damaged the Friant-Kern Canal,” Eric

Parfrey, then-chairman of the Sierra Club California’s executive

committee, wrote in a September 2018 op-ed published in

newspapers around the state. “Those who caused the damage should

pay to repair the canals.”

“Overpumping of aquifers caused the

groundwater subsidence that damaged the Friant-Kern Canal,” Eric

Parfrey, then-chairman of the Sierra Club California’s executive

committee, wrote in a September 2018 op-ed published in

newspapers around the state. “Those who caused the damage should

pay to repair the canals.”

Jerry Meral, the author of Proposition 3, acknowledged that even though it was less than 10 percent of the $8.8 billion bond, the Friant-Kern Canal portion of the initiative weighed against its passage.

“I think if the Friant provision hadn’t been in there, it would have passed,” he said. “However, without the support of the people in the Friant area, it wouldn’t have got on the ballot, so we were caught between the two conundrums there.”

In an interview, Parfrey with the Sierra Club said there might be a state role for addressing the subsidence problem, provided it comes through the legislative process subject to public review. Proposition 3, he said, “was just kind of insulting because it was so obviously a pay-to-play type of arrangement.”

Sinking an inch a month

Completed in 1949 as part of the federal Central Valley Project, the Friant-Kern Canal is operated and maintained by the Friant Water Authority. The canal starts from Millerton Lake near Fresno with a capacity of 5,300 cubic feet per second (cfs) and ends south of Bakersfield with a capacity of 2,500 cfs.

Along the way, it supplies water to

three of the top crop-producing counties in California: Fresno,

Tulare and Kern.

Along the way, it supplies water to

three of the top crop-producing counties in California: Fresno,

Tulare and Kern.

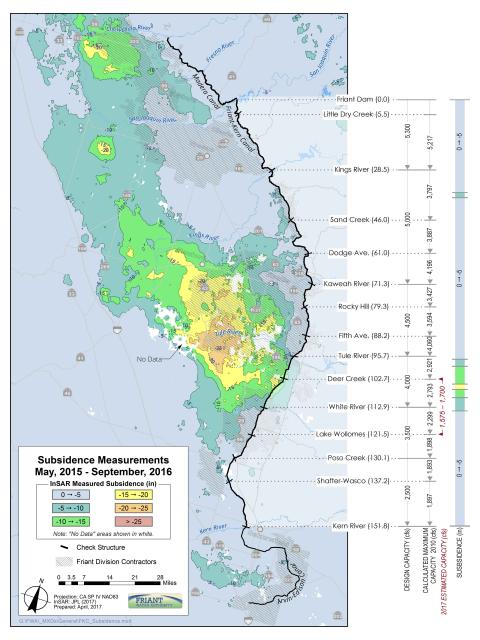

The worst subsidence area exists at the 102-mile mark, west of Porterville in Tulare County, where the canal has lost more than 1,000 cfs of capacity since 2010. Between 2015 and 2017, the canal dropped an inch per month, denying the ability to convey an estimated 300,000 acre-feet that could have been delivered during a wet 2017, according to Alex Biering, government affairs and communications manager with Friant Water Authority. That’s a problem for a canal that moves water purely by gravity.

The $750 million in Proposition 3 most likely would have been used to restore the entire capacity of the Friant-Kern and Madera canals (at an estimated cost of $450 million), with the remaining funds targeted at other conveyance capacity improvement projects in the valley, Biering said.

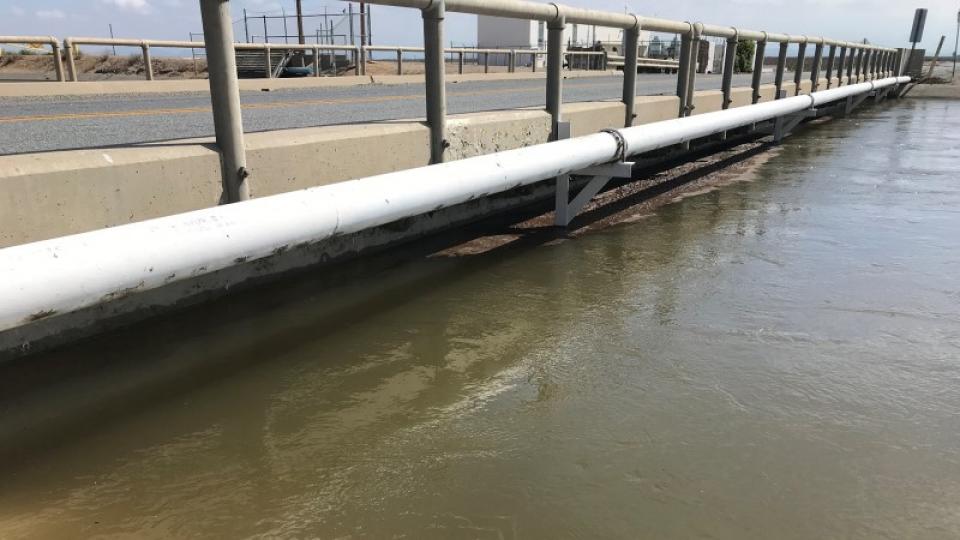

The authority is pursuing immediate repairs to increase the capacity of the canal to the level of historic deliveries. Part of the repair work includes adding a waterproof coating or membrane to five county bridges to help the water slide past the vertical face of the bridges that it’s now hitting.

“We can have a wet year, with plenty of water to recharge, but with capacity restrictions on the canal, we are only able to bring a portion of that water into the district. It’s like being given a full glass of water but limited to using a straw the diameter of a straight pin to drink from it.”

~Mark Larsen, general manager of the Kaweah Delta Water Conservation District in Tulare and Kings counties.

But there is the need for a “longer-term, broader fix,” Biering said.

“Whether it ends up being a full restoration of the canal’s design capacity from the dam to its terminus (4,000 cubic feet per second) or whether it will be specifically focused on the subsidence area, those are questions that remain to be answered by our board,” she said.

It also remains to be seen whether funds are found to improve the canal to help facilitate SGMA-related groundwater recharge.

“It is possible that the bigger fix to the canal could support conveying water not just to satisfy Friant contracts, but to expand water deliveries for groundwater banking to implementation of SGMA,” Biering said. “Had Prop. 3 passed, we likely would have been interested in restoring the full design capacity of the entire canal. Under that scenario, it’s possible that the additional conveyance could have helped with SGMA compliance.”

‘Needs a lot of dollars’

Water contractors south of the Delta say they have been forced to turn to groundwater pumping because of the unreliability of deliveries from state and federal pumping facilities.

Cannon Michael, chief executive

officer of Bowles Farming Company in Los Banos, said subsidence

is a large-scale problem that is affecting water conveyance for

agriculture as well as groundwater banks and wildlife refuges. As

such, it is difficult for the agricultural community to pledge

unlimited financial support for the solution.

Cannon Michael, chief executive

officer of Bowles Farming Company in Los Banos, said subsidence

is a large-scale problem that is affecting water conveyance for

agriculture as well as groundwater banks and wildlife refuges. As

such, it is difficult for the agricultural community to pledge

unlimited financial support for the solution.

“It’s one of those things that needs a lot of dollars,” said Michael, whose water deliveries arrive via the also-sinking Delta-Mendota Canal, another piece of the federal Central Valley Project. “The bond not passing was a bitter disappointment for folks, but ultimately people are still looking for the solution.”

Michael noted that the Central Valley Project was constructed in part to help slow the rate of groundwater pumping in the San Joaquin Valley. Action is needed, he said, to restore that surface water reliability.

“We need the infrastructure to function properly to do all the creative things we do … otherwise we are going miss a lot of opportunities.”

Farmers are especially concerned about their inability to take water deliveries during wet years when more is available for groundwater recharge.

“We use our contract for San Joaquin River water primarily for groundwater recharge and having limitations on the ability to push water through the Friant-Kern Canal restricts our ability to do that,” said Mark Larsen, general manager of the Kaweah Delta Water Conservation District in Tulare and Kings counties. “It strikes me that we can have a wet year, with plenty of water to recharge, but with capacity restrictions on the canal, we are only able to bring a portion of that water into the district. It’s like being given a full glass of water but limited to using a straw the diameter of a straight pin to drink from it.”

About 50 miles south of the Kaweah

district, Quinley with the Delano-Earlimart district said the

constraint on the canal “eliminates one of the variables in our

water portfolio,” the ability to take available flood flows.

About 50 miles south of the Kaweah

district, Quinley with the Delano-Earlimart district said the

constraint on the canal “eliminates one of the variables in our

water portfolio,” the ability to take available flood flows.

Furthermore, there is the question of what to do about the pumping outside the Friant service area that causes the subsidence problem.

“You have a lot of lands that are planted in permanent plantings outside the irrigation district completely … that are much more reliant on groundwater or wholly reliant on groundwater,” he said. If those areas are contributing to the subsidence problems that impair the canal, “how can we put something together where we have acknowledgement and mitigation related to the potential damage that’s caused by that overdraft?”

Finding the best alternatives

While agencies such as the Friant Water Authority confront what to do about subsidence, the work on SGMA continues, including completing sustainability plans that outline how groundwater recharge will occur in the hardest-hit areas.

“The farmers created this problem of subsidence and now they are going to the city people to get a bailout to fix the problem that their overpumping created. The optics of that are not real good.”

~ Eric Parfrey, member of the Sierra Club California’s executive committee.

“SGMA has to be implemented and to do that, it is going to require more capacity in the canal,” Meral said. “The problem is the Friant-Kern people will probably only want to pay for the repair of the canal to the extent that they can get their full Class 1 (regular) and Class 2 (wet year) deliveries and not necessarily more. They’ll have to talk to people who would benefit from conveyance of extra water in Tulare and Kern counties primarily and see whether a willingness is [there] to pay and bring the canal up to a higher capacity to convey water to groundwater basins.”

The scope of repair means spreading the costs across as broad a base as possible, which will be a challenge.

“Although we’d like to have a large pool of partners sharing the costs of repairing the canal, it tends to be those most impacted that pay,” said Larsen with the Kaweah Delta Water Conservation District. “There are some on the canal that have said they won’t be partnering on the project because they are upstream of the subsidence problems, and it does not affect them.”

Parfrey with the Sierra Club said his

organization is “totally opposed” to overturning the

beneficiaries-pay principle when it comes to funding subsidence

repair.

Parfrey with the Sierra Club said his

organization is “totally opposed” to overturning the

beneficiaries-pay principle when it comes to funding subsidence

repair.

“The reason why we have subsidence down in the valley is because there has been a grotesque amount of overpumping by the farmers, so in essence when city people look at the situation they say, ‘Well, the farmers created this problem of subsidence and now they are going to the city people to get a bailout to fix the problem that their overpumping created,’” he said. “The optics of that are not real good.”

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.